The latest free exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands is Secret Rivers. Open from 24 May to 27 October 2019, it combines art and archaeology with mudlarking, photography, film and much more to uncover the mysteries of London’s rivers – both those that flow above ground and those that have been buried beneath our feet.

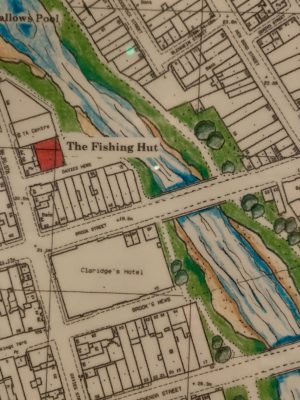

A large wall map shows us the routes of the hidden waterways across the capital and there are so many! Some London street names give clues to their locations (Westbourne Grove, Effra Road, Fleet Street, etc) but this exhibition helps you understand these elusive tributaries.

This photograph from Andy Sewell’s series ‘The Heath’ depicts a man swimming in one of the swimming ponds on Hampstead Heath. Created by damming two streams, these ponds outflow into the subterranean River Fleet, which now forms part of London’s sewer network. Sewell has described this series of images as an attempt to explore the condition of ‘biophilia’ by which people are drawn to seek connections with nature. The Hampstead swimming ponds are one of the few places where Londoners can safely swim in a remnant of a lost river.

Not Just The Thames

The rivers, brooks and streams of London have had a huge impact on this city over the centuries. While we are all aware of The Thames, this exhibition also explores the Effra, Fleet, Neckinger, Lea, Tyburn, Walbrook, Wandle and Westbourne.

While the Thames has been vital to the international trade that made London such an important city, the exhibition looks at how we use our rivers from transport and sustenance to sewers and drains.

All in the Detail

The exhibition teems with curious facts about London’s rivers. For example, the Walbrook, which was buried in the 15th century, flows beneath the Bank of England and was spotted during building works there in 1732 and 1803. The Oval Cricket Ground in Kennington is shaped around a curve of the Effra and its seating banks were built using soil excavated when the river was covered. And one that’s in plain sight but easily missed, the Westbourne flows through a pipe over Sloane Square underground station.

The one that shocked me was that before Britain was segregated from Continental Europe, The Thames was a tributary of the Rhine!

The exhibition took less than a year to plan, even with newly-commissioned works, and is divided into 7 sections.

Secrets of The Thames

While The Thames certainly isn’t a secret river, it does hold some little known stories.

On display is a wonderful notebook by a mudlarker – someone who explores the foreshores for interesting finds. He writes about his discoveries and also paints pictures too. And there’s a middle Bronze Age crania (skull without the lower jaw bone) on display from 43 that were found in Mortlake.

Sacred Rivers

The Walbrook has long since been covered over but it was a major feature of Roman Londinium. It was valued for industry including metal working, milling, and water supply and it was also sacred.

The Thames of Roman London was much wider than today and in places it divided into several channels with islands between them. The Romans believed that rivers were a means of direct communication with the gods; a boundary between the physical and spiritual words. Roman temples were built close to the water, often to make offerings to water gods.

Biography of a River

Before it began to be buried in the late 18th century, the River Fleet would have been considered London’s second river. It flowed from Hampstead and Highgate to the Thames at Blackfriars Bridge.

Efforts had been taken to clean the river. It was scoured out in 1598, 1606 and 1652 but industries along its banks continued to throw their waste into the water. Householders also threw their sewage into it so it was soon clogged with filth again. Medieval leather work was polluting water for brewing creating pollution for monks.

The canal was not only dirty and dangerous, it was also unprofitable. And it was for this reason that it began to be covered over. In 1733 the section between Holborn Bridge and Fleet Bridge at Ludgate Circus was arched over to form Fleet Market (now part of Farringdon Street). The rest down to the Thames was covered in 1766, making this part of the river an official sewer. A used and abused river, other parts of the Fleet were progressively covered over until the whole river was incorporated into the London-wide combined sewer network where it still flows today.

The Fleet’s long history is told through previously unseen archaeological artefacts including rare surviving fragments of the 13th-century Blackfriars Monastery, dissolved by Henry VIII in 1528. The remains were used to line a local well, which was excavated 450 years later. Other exhibits show that the river was a source of food (a medieval fish trap) before filling up with rubbish, including bones from Smithfield market and the waste from the many industries and houses along its banks.

Toilet Seat

As well as the over life-size video wall of entering a sewer (you feel like you’re there without the smell, rats and ‘waste’), there is a very old toilet seat on display.

Can you imagine your own toilet seat on display in a museum 900 years from now? This 12th-century toilet seat has three holes so clearly going to the loo was a communal affair.

This toilet seat was found lying over a cesspit. It was located in a yard behind buildings that faced onto Fleet Street (modern day Ludgate Hill). These buildings were constructed on the infilled channel of the southern Fleet island. The tenement included commercial, residential buildings and stores as well as a yard planted with trees. Records from the 14th century show that the tenement was known as ‘Helle’ and was owned by John de Flete, a capper (cap-maker), who left it to his wife Cassandra.

While many people built their toilets over the Fleet so the river would wash everything away, this was banned in 1463.

The row of buildings was first built in the second half of the 12th century. They survived until the area was heavily damaged by bombs during the Second World War. They were some of the longest-surviving London buildings, remarkable given that this minor row of buildings was associated with neither royalty, governance or religion.

Visitors can sit on a recreation of the historic latrine for a popular photo opportunity.

As air drying this type of archaeological find can cause irreparable damage, the waterlogged toilet seat was impregnated with special waxes to take up some of the space previously occupied by water. It was then put in the Museum’s freeze dryer then into storage for 26 years.

You can also see these cat and dog skulls with a dog’s collar. The collar has the inscription: ‘Tom at Ye Greyhouse, Bucklersbury’. Bucklersbury is within the City of London near the route of the Walbrook. How did the collar end up in the River Fleet? The Fleet was infamous for being polluted with dead dogs. Alexander Pope wrote in 1728: ‘To where Fleet Ditch, with disemboguing streams, Rolls the large tribute of dead dogs to the Thames’.

Pleasure and Poverty

Did you know, the Serpentine Lake in Hyde Park is an artificial lake? It was originally created along the course of the Westbourne by damming the stream and linking together a number of natural ponds. The work was overseen by the Royal Gardener Charles Bridgeman in the 1730s at the command of Queen Caroline.

This watercolour depicts a view of the Flora Tea Gardens with animals grazing by a stream. This is Bayard’s Watering Place, from which Bayswater gets its name, and the stream is the Westbourne which once flowed from Hampstead through Kilburn, Bayswater, Hyde Park (where it fed the Serpentine lake) and through Chelsea to the Thames. During the nineteenth century the river was driven underground as the area through which it flowed was built over and the waters became polluted with sewerage. It still flows through pipes as part of the Ranelagh Sewer, part of which bridges the platforms of Sloane Square tube station.

The canal forms the focal point of this coloured print depicting a masquerade at Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea. A pavilion – the ‘Chinese House’ – has been built over the lake and wealthy visitors enjoy the spectacle in fancy dress. This ‘pond’ formed a particular ‘wonder’ at night when it reflected ‘thousands of gay lamps’ (Robert Bloomfield, A Visit to Ranelagh, 1802.)

The Chelsea Waterworks Company was established in 1723 to provide drinking water to the western districts of central London and drew water from the Thames supplemented by the Westbourne. This engraving shows a pump house at the left with a water tank and pipes made out of bored logs laid out before it.

Situated between the Thames, the outflow of the River Neckinger at St Saviour’s Dock and two tidal ditches, Jacob’s Island in Bermondsey was a notorious slum in the early nineteenth century.

People lived in a ‘rookery’ alongside tanneries, lead and flour mills, waterworks, stave merchants and corn merchants. These industries were highly polluting, not just of the water but the land as well.

This large and highly detailed watercolour by James Lawson Stewart (1887) depicts two rows of dilapidated buildings was wooden galleries overhanging a waterway filled with stagnant water. It recalls Folly Ditch, immortalised as the site of Bill Sykes’s drowning in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837-39). In the mid-nineteenth century, the poor residents had no source of clean water and many had to use water from the foul ditch into which they also discharged their waste. The water often ran red with pollution from the nearby leather tanning industry. Described in the Morning Chronicle as ‘the Venice of drains’, the area became a cholera hotspot in 1849.

This 19th-century ceramic mug was found among the domestic waste in Jacob’s Island and has the inscription ‘For a Good Girl’. It highlights the children living in these awful conditions. By the mid-19th century, the diseases and the squalor were a matter of public concern.

Daylighting

This was a new term to me. It means trying to uncover hidden rivers to bring them to the surface again. Sections of the Moselle, the Quaggy and the Wandle have all been ‘daylighted’ in recent years. Restoration is costly but provides wildlife habitats and sustainable flood protection as well as improving the quality of urban life by reintroducing green spaces.

A 1992 project to unearth the Effra was more of an art statement than a true consideration as 27 years later the river remains buried as a storm drain from Norwood to Vauxhall.

I wish the Tyburn Angling Club well with their campaign to daylight the Tyburn through Mayfair but we know no-one is going to knock down that prime real estate.

Renewal

Although the Wandle has largely remained an open river, small sections have been buried including the streams forming the eastern source at Croydon.

The Wandle rises in Croydon and once ran through the town past the Church of St John the Baptist where it was known as the Croydon Bourne. A report of 1848 found that the river was being used as an open sewer. As a result, clean water and sewer pipes were provided and the Wandle was covered over.

These two photographs taken almost 20 years apart, show the same view of the River Wandle at Merton. This was the site of Merton Priory between 1117 and 1538.

And these views are on the Olympic Park in east London.

Tracing the River

This final section has contemporary artworks that use rivers as a source of inspiration.

There is a large projection installation here but, I’ll admit, even after reading about it I don’t understand it. The scale, movement and speed is controlled by environmental data collection in real time by 38 monitoring stations along the River Lea. Data Flow (River Lea) will, therefore, change all the time.

You’ll need at least an hour to enjoy this free exhibition but it’s fascinating so you are likely to stay longer.

Contact Information

Exhibition Name: Secret Rivers

Dates: 24 May to 27 October 2019

Admission: Free

Address: Museum of London Docklands, West India Quay, No.1 Warehouse, Hertsmere Rd, London E14 4AL

About the Museum: Opened in 2003, this Grade I listed converted Georgian sugar warehouse specifically tells the story of the port, river and city – focusing on trade, migration and commerce in London. The museum is open daily 10am to 6pm and is free to all.

Official Website: www.museumoflondon.org.uk/museum-london-docklands/whats-on/exhibitions/secret-rivers

Special Events: There is a full programme of walks, talks, boat trips and family activities planned throughout the exhibition.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!