The 1951 Festival of Britain was a post-war state-sponsored exhibition. At the time, rationing continued and austerity gripped the nation. London was shabby, rundown and gloomy so this bright and playful spectacular was a ‘tonic for the nation’ to promote the feeling of recovery. The city was scarred with bombsites and buildings hadn’t been painted for ten years so the Festival of Britain brought colour and fun; a bright new future for a brave new world.

The Idea

The idea of a national festival was discussed as early as 1943. However, it was when Gerald Barry, the editor of the News Chronicle, wrote an open letter in the paper to Stafford Cripps, the President of the Board of Trade, that the idea started to gain support. It was discussed in Parliament in 1947 and the Labour MP and cabinet minister Herbert Morrison (MP for South Hackney and former leader of London County Council) was placed in charge of the planned festival. (His grandson, Peter Mandelson would later be responsible for the Millennium Dome). Many of the themes of the festival were aligned with the thinking and policies of the Labour government at the time.

The Festival of Britain was a celebration of all aspects of design from arts and science to technology and innovation. It was a national celebration in over 2,000 locations with London’s South Bank as the main site.

Great Exhibition of 1851 Centenary

1951 happened to also be the centenary, almost to the day, of the 1851 Great Exhibition. This seems to be more of a happy coincidence than the main purpose for choosing summer 1951.

The 1851 exhibition was an international exhibition with manufactured goods from across the world whereas the 1951 exhibition was focused on British industry. Rather than being a world fair, the Festival focused entirely on Britain and its achievements and being a beacon for change. Funded mostly by the government with a budget of £12 million, it intended to demonstrate Britain’s contribution to civilisation, past, present and future, in the arts, in science and technology, and in industrial design.

Festival Poster

Abram Games had been the ‘Official War Poster Artist‘ during the Second World War (1939–45). His designs for the Festival of Britain incorporated heraldic imagery and angular geometry to create a modern portrait of the national character. This emblem featured on posters, leaflets, souvenirs and catalogues, helping to create what would become known as ‘Festival Style’.

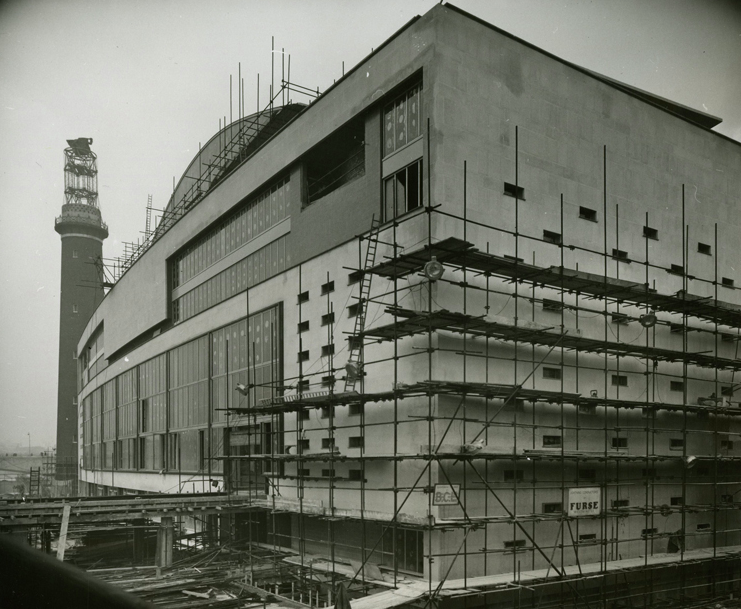

Photo © John Ritchie Addison (cc-by-sa/2.0)South Bank

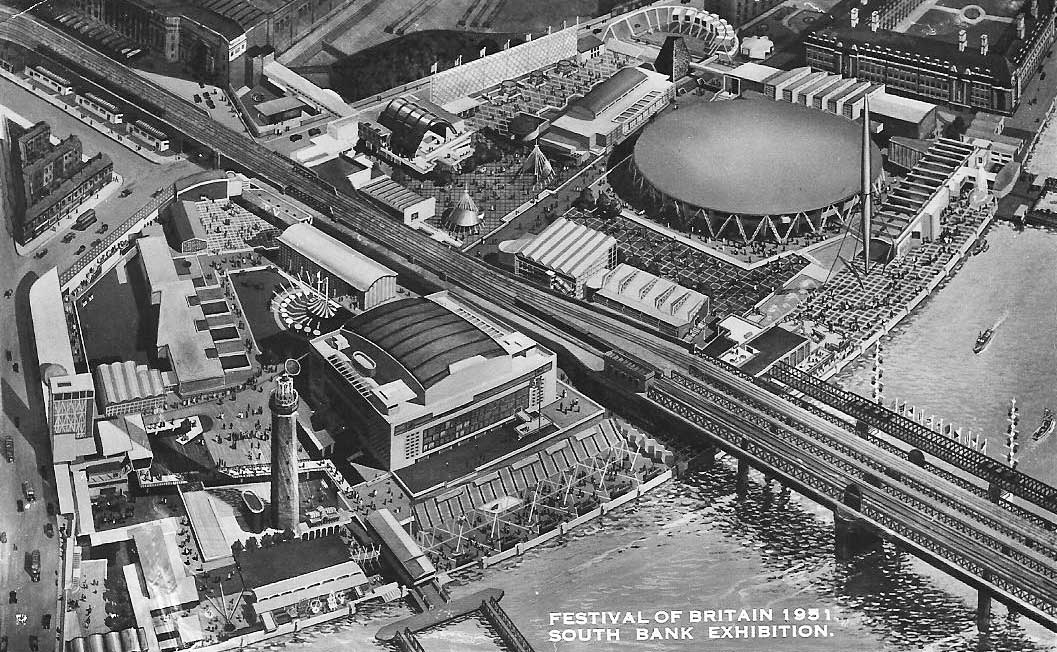

The South Bank site was intended as the beating heart of the national celebrations. Have a look at a map to see what was there. To help you orientate yourself, the current Festival Pier is where the Rodney Pier was located during the festival.

The land here was a badly bombed industrial area. There were some warehouses left and working-class housing.

You can see more construction images here (City of London Collage) and more on the transformation here (A London Inheritance blog).

This 27-acre wasteland became a fantasyland with 22 freestanding pavilions featuring temporary and experimental architecture. 38-year-old architect Hugh Casson was appointed Director of Architecture and he then appointed further young and radical architects to design the South Bank buildings. Most were designed in the International Modernist style, incorporating multiple levels of buildings, elevated walkways and open interiors.

There was no processional way and no symmetry. Instead, it was planned like rooms of different shapes and sizes. There was a suggested route to follow that would take you on a journey from early geology, the first human arrivals and the later waves of immigration that would build the British population.

On a waterside location, The Thames was part of the show with light open railings beside the water and balconies suspended above it. A barge dock that had been exposed by the bombing was patched-up and painted to serve as a yacht basin. And a rickety Bailey bridge was erected over The Thames by the Royal Engineers to link to the north bank.

Trees and grass were planted to act as a barrier to the soot-covered ‘outside world’. (We all had coal fires at home so all London buildings were black with soot.) The bright colours here offered a festival gaiety. It was described as being like a gigantic toyshop for adults with a series of surprises. Like waking up from a deep sleep and looking into the future. And for most ordinary people, it brought light-hearted relief and fun.

Artworks

There were over 30 sculptures on the South Bank site and the Festival of Britain was one of the first occasions where many female artists could widely take part. The sculptor Barbara Hepworth received two commissions.

Contrapuntal Forms was later acquired by the Harlow Development Corporation. It was intended that the sculpture would move to the town centre once the Civic Square was complete. This was thwarted by residents, who insisted it remain in the residential area where it still stands today. It was given a Grade II listing by English Heritage in 1998. You can see it now as part of the Harlow Sculpture Town Trail. (I discovered the current location of this artwork when @MuseumMum visited the trail recently.)

Another Grade II listed sculpture from the Festival that we can still see is London Pride by Frank Dobson. This one has stayed closer to its original location and is now outside the National Theatre.

Royal Festival Hall

Designed by Sir Robert Matthew, Dr Leslie Martin and Sir Hubert Bennett, the Royal Festival Hall was built especially for the Festival. It was always planned as a permanent structure to remain after the summer festival ended as a new 2,900-seater concert hall and a centre for the musical life of London.

See more photos taken during construction.

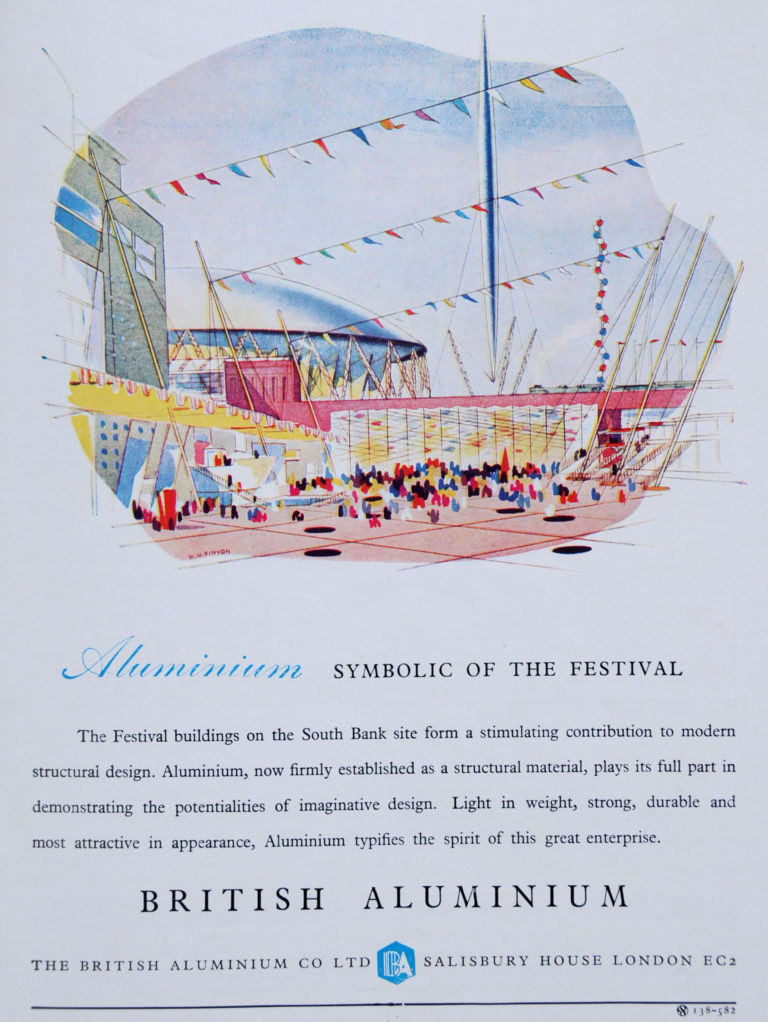

Dome of Discovery

The Festival took pride in Britain’s past highlighting and celebrating Britain’s achievements in discovery as well as great British scientists. And it also looked to the future with experimental modern architecture. The Festival had several unique temporary buildings including the Dome of Discovery. Considered a work of art as well as a feat of engineering, this was the largest dome in the world at the time standing 93 feet tall with a diameter of 365 feet. This was also the largest aluminium building in the world at the time of the Festival.

It housed exhibitions on the theme of discovery such as the New World, the Polar regions, the Sea, the Sky and Outer Space. It also included a 12-ton steam engine on show. Due to its light structure, the Dome could flex in the wind.

Skylon

This steel and aluminium futuristic tower appeared to ‘float’ above the ground supported by tension cables. (There was lots said at the time about how it had no visible means of support and comparisons were made to the British economy.)

Adjacent to the Dome of Discovery, this iconic cigar-shaped 300 ft rocket was built to astonish visitors. Apparently, the evening before the Royal visit to the main Festival site, a student is known to have climbed to near the top and attached a University of London Air Squadron scarf!

Sadly, the Skylon was one of the structures that the Conservative government ordered to be removed after the end of the Festival. It is remembered with the Skylon restaurant on the third floor of the Royal Festival Hall.

Parts of the Skylon and the Dome of Discovery ended up melted down as souvenir paper knives.

Telekinema

This was the first cinema in the world to be specially designed and built to show both films and large-screen television. This 400-seat state-of-the-art cinema was operated by the British Film Institute and could offer 3D films with surround sound. It showed live broadcasts from across the South Bank site along with a series of documentaries specially produced for the Festival.

The Telekinema was extremely popular and it was here that many visitors saw their first-ever television pictures.

After the Festival closed, the Telekinema became home to the National Film Theatre. The building was later demolished in 1957 when the NFT moved to the site it still occupies nearby.

The Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion

The Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion presented British people covering ‘Language and Literature’, ‘Eccentricities and Humours’, ‘Skill of Hand and Eye’ (British craftsmanship), ‘The Instinct of Liberty’ and ‘The Indefinable Character’ (what it means to be British).

Homes and Gardens Pavilion

With so many new homes needed after WWII, this pavilion looked at a new British family home. The six rooms on display were:

- The child in the home

- The bed-sitting room

- The kitchen

- Hobbies and the home

- Home entertainment

- The parlour

In each, you could see the types of products that the consumer could expect to purchase in the future to use within and decorate each room. With wood still rationed, furniture designers had to find ways to incorporate alternative materials such as aluminium or steel.

One of the most famous and long-lasting chairs produced for the Festival was Robin Day’s 658 chair. This was originally developed for the Royal Festival Hall and was known as the Royal Festival Hall lounge chair. With its swan-like curves and wide proportions, Day’s bent plywood and steel leg chair had massive appeal.

Robin Day, together with his wife, textile designer Lucienne Day, became one of Britain’s most celebrated post-war designers. Her most recognised textile design, Calyx, was a striking departure from the typical floral prints that were commercially available at the time. The vibrant fabric embodied the spirit of the Festival and went on to become a commercially successful product at Heal’s.

You can see a short film of home movie footage from the Festival of Britain here.

Elsewhere in London

It wasn’t all on the South Bank in London as a new wing of the Science Museum in South Kensington held the Exhibition of Science. There was also The Exhibition of Live Architecture in Poplar in east London and the Festival Pleasure Gardens in Battersea in south-west London.

Poplar

In east London, a new housing estate was built as a ‘live architecture exhibition’. Designed to incorporate all the latest thinking about architecture, town planning and communities, the Lansbury Estate consisted of a shopping precinct, a library, a Building Research Pavilion, a Town Planning Pavilion and a building site showing houses in various stages of completion. It was essentially about making life better for people currently living in sub-standard housing. The Building Research Pavilion had a “Gremlin Grange” that highlighted what goes wrong when scientific building principles are not employed, such as structural cracks and leaning walls due to bad foundation design and damp rising up the walls because there is no damp course.

The Exhibition of Live Architecture was never as popular as the South Bank site of the Festival. It wasn’t in central London and travel involved a boat and buses. Plus it didn’t have the excitement of the Pleasure Gardens.

You can see a walk around the area with recent photos on the A London Inheritance blog.

Battersea

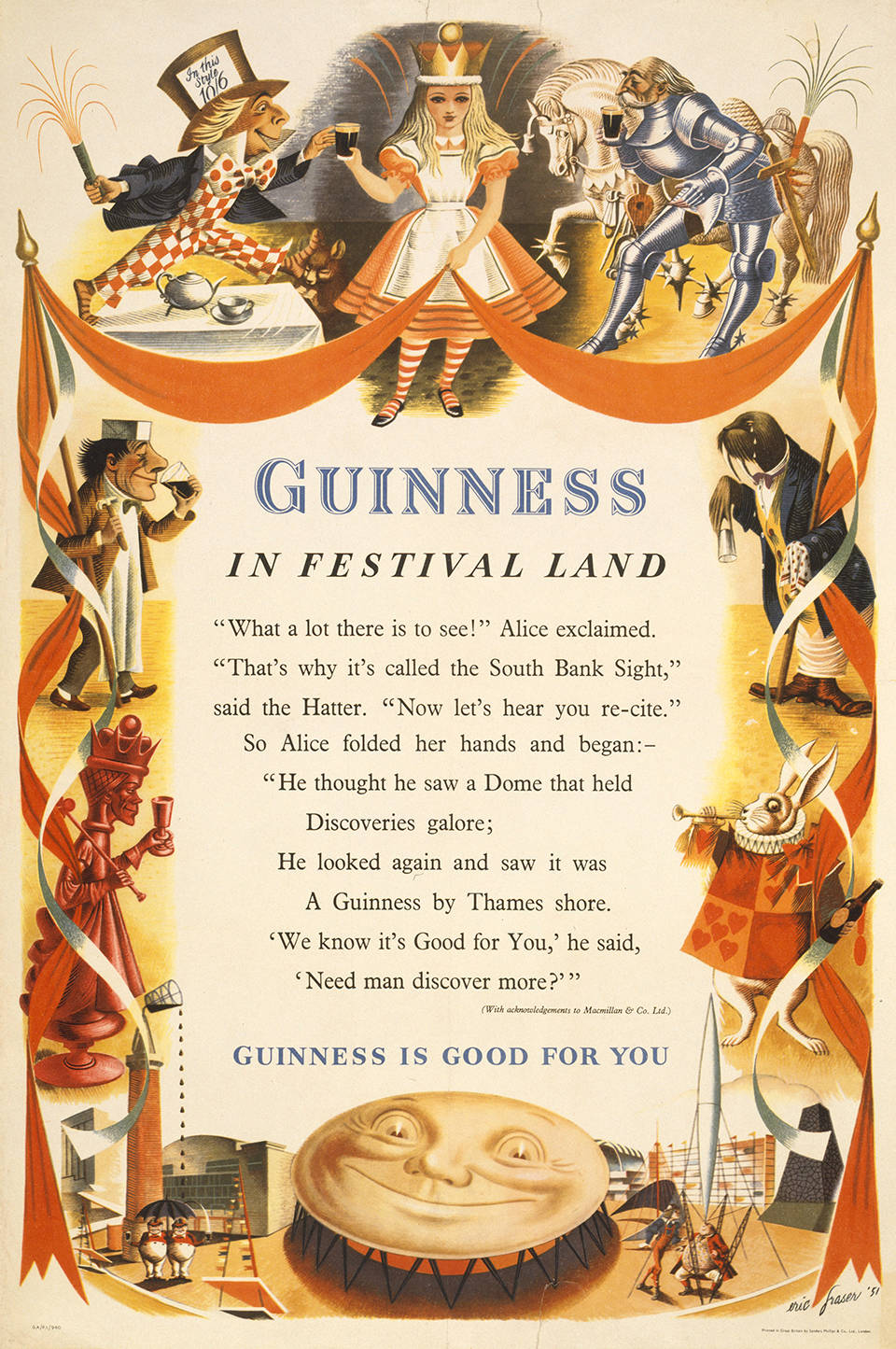

This large funfair was a fantastic day out; the perfect antidote to the grey previous decade. A boat connected the South Bank and Battersea Park for the Pleasure Gardens, fairground rides and open-air amusements. This was all about fun rather than education or cultural edification. Visitors talked about coming away feeling energised and happy.

This was the one commercially-sponsored area of the Festival. Guinness provided a 25-foot high mechanical clock and an Alice in Wonderland parody poster with the story’s characters drinking a pint of the black stuff. The beaming face at the bottom is on the canopy of the Dome of Discovery.

Can you imagine an alcohol and children’s story collaboration today? I think not.

Nationwide

There were exhibitions of art and design in many towns and cities across Great Britain. Heavy engineering was the subject of the Industrial Power exhibition in Glasgow and there was the Ulster Farm and Factory Exhibition in Belfast.

There were also two travelling exhibitions. The land travelling exhibition visited four cities, and the Festival ship Campania went to ten major ports around the coast to tell the story of Britain and her people.

Controversy

As with most large government-sponsored and funded projects, the Festival met with much controversy. There was widespread criticism of the expense during a time of austerity when so much public housing was needed. There was rivalry from the press as The Observor were involved in the organisation so the Festival was hated by the Daily Express. And as a Labour government were funding the project, it was despised by Churchill and the Conservative government who took power in October 1951.

Success

The Festival of Britain was opened on 3 May 1951 by King George VI. After a special service attended by the King, Queen Elizabeth, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret and other senior members of the royal family, King George declared the festival open in a broadcast from the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. A 41-gun salute was fired at the Tower of London and Hyde Park.

Later in the afternoon, the King and Queen attended a service of dedication led by the Archbishop of Canterbury at the Royal Festival Hall. And there were 2,000 campfires lit across Britain.

This summer festival acted as a national morale-booster. Even though the entrance fee for the Dome of Discovery was five shillings, the South Bank Festival site still saw 8.5 million paying visitors. The Pleasure Gardens had over 8 million visitors (three-quarters of these were Londoners) and the Campania ship was visited by almost 900,000 people.

In the evening there was open-air dancing in a city when not long before we had been living through blackout so the twinkling lights at night were a wonder. So many of the authoritarian directions known in everyday life (queue here, etc) didn’t exist at the South Bank site so it felt open and liberating. While the Festival certainly provided light-relief it also managed to project the feeling that there was more to life than just existing. (The toilets had soft toilet paper – the first time it had been introduced to the British public!)

The Festival also acted as a catalyst for a new design aesthetic, launching the career of noted British designers working in the fields of textiles, furniture and graphic design. Many of the designs originally produced for the Festival have been acquired for the V&A’s collections.

Always planned as a temporary exhibition, the Festival ran for five months before closing in September 1951. It had been both popular and profitable.

A month later, on 25 October 1951, a new Conservative government was elected led by an ageing Winston Churchill. It is generally believed that Churchill considered the Festival a piece of socialist propaganda; a celebration of the achievements of the Labour Party and their vision for a new Socialist Britain. So, as you can imagine, he didn’t like it at all. He ordered the South Bank site to be cleared to remove almost all trace of the much-loved Festival of Britain. The Royal Festival Hall was built to be permanent so that was allowed to stay.

But the area was never going to be returned to industrial use and the legacy as a location of culture remained. In the 30 years that followed, the Festival the site was developed into the South Bank Centre (an arts complex which now houses the Royal Festival Hall), the National Film Theatre, Queen Elizabeth Hall and the National Theatre. (The BFI has a wonderful short film, available to view for free, about the Festival.)

What Remains?

As well as the legacy of an arts and culture site, the Royal Festival Hall is still on the South Bank. It was refurbished in 2005-7 and is now a Grade I listed building – the first post-war building to become so protected.

For some comparison photos with today, have a look at the A London Inheritance blog as his father took photos during the Festival and he has been back to see the locations. It includes a brass ring fixed to the ground which was used as a viewing point for the Skylon (I spotted it in one of the films I watched but can’t remember which – sorry!) I do wonder if it is still there so will look out for it when central London strolls become a possibility again.

I’ll also look out for this flagpole when I’m next there too. (The Dome of Discovery plaque was, sadly, never reinstated.)

The ‘South Bank lion’ wasn’t part of the Festival of Britain but it did stand on top of The Lion Brewery that was demolished to make way for the Royal Festival Hall. The building had suffered a fire in the 1930s and was being used as stables and as a warehouse. The lion that sat on top of the building was saved and was initially placed outside Waterloo station and then moved to the southern end of Westminster Bridge in the 1960s. (More info on the IanVisits website.)

You can see it in situ before demolition on this blog post and in its current location on this blog post.

Apparently, after the Festival of Britain ended, the organisers offered all of the artwork commissions to councils and arts bodies across the country which is how Harlow in Essex ended up with Barbara Hepworth’s Contrapuntal Forms. I’d love to know where other artworks can be seen across the country.

The artworks may well be in the other ‘new towns‘. Many of the principles on show at Lansbury Estate development in Poplar, east London, such as the use of mainly low-rise housing and green space was used in the new towns. While Chrisp Street market was the first purpose-built pedestrian shopping area in the UK, its design has been repeated across the country. On the edge of Chrisp Street is The Festival Inn which still uses the festival symbol on its pub sign hanging outside. And something that would be easy to miss is the estate drainpipe rainwater hoppers.

And More

If you’d like to know more about the Festival of Britain and hear from those involved with the production and visitors, this is an excellent programme. It’s about an hour-long so sit back and enjoy.

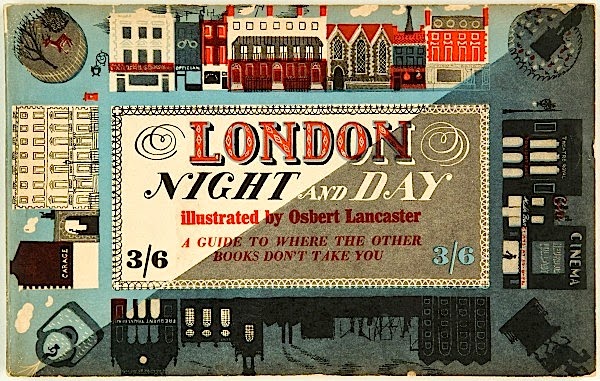

And this book is fabulous to discover what else there was to see in London in 1951. It was sold at the time as the alternative guide. I got my copy from Abe Books.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!