From Victorian Engineering Marvels to Modern Mega-Projects

Beneath the murky waters of the River Thames lies one of London’s most remarkable achievements—a complex network of tunnels that has been growing for nearly two centuries. From the world’s first underwater tunnel to the latest super sewer protecting the river from pollution, these subterranean passages tell the story of London’s evolution from Victorian metropolis to modern megacity. With approximately 45 tunnels beneath the Thames, including 20 open to the public and at least 25 more that most of us can’t access, London has become one of the most tunnelled cities in the world.

The Thames, both London’s lifeblood and its greatest natural barrier, has challenged engineers for centuries. Today’s commuters take for granted their ability to cross beneath the river on the Tube, by car, or even on foot. Yet each of these crossings represents a triumph of engineering, often achieved against seemingly impossible odds and at tremendous human cost. As London opens its newest crossing—the Silvertown Tunnel in April 2025—it’s worth diving deep into the remarkable history of how we conquered the Thames from below.

The Pioneer: Brunel’s Thames Tunnel (1825-1843)

The story of Thames tunnelling begins with Marc Isambard Brunel and his revolutionary Thames Tunnel, the first tunnel known to have been constructed successfully underneath a navigable river. This wasn’t London’s first attempt at a sub-Thames crossing—an earlier effort in 1807 had failed dramatically when workers hit quicksand after just 1,000 feet. But Brunel, a French-born engineer who had fled to Britain during the Revolution, brought something new to the table: the tunnelling shield.

Brunel patented his revolutionary tunnelling device in 1818: a special rectangular, cast-iron shield that supported the earth while miners dug it away in small increments. The shield was an ingenious contraption, consisting of twelve great frames, lying close to each other like as many volumes on the shelf of a book-case, and divided into three stages or stories, thus presenting 36 chambers of cells, each for one workman. Workers would excavate the earth in front of them board by board, with bricklayers following behind to construct the tunnel lining.

Construction began in 1825, with Brunel assisted by his son, the future engineering legend Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The project was plagued by disasters—floods, gas leaks, and financial crises that would have defeated lesser men. The Thames broke through the tunnel roof five times during construction, killing six workers. During one flood in 1828, Isambard nearly drowned and was laid up for months recovering from his injuries. The tunnel was sealed for seven years due to lack of funds before work resumed in 1835.

When it finally opened in 1843, the Thames Tunnel had taken 18 years to complete and cost £454,000—far exceeding its original budget. It measures 35 ft (11 m) wide by 20 ft (6.1 m) high and is 1,300 ft (400 m) long, running at a depth of 75 ft (23 m) below the river surface measured at high tide. Though originally intended for horse-drawn carriages, the approaches were never built due to cost, and it became a pedestrian tunnel instead.

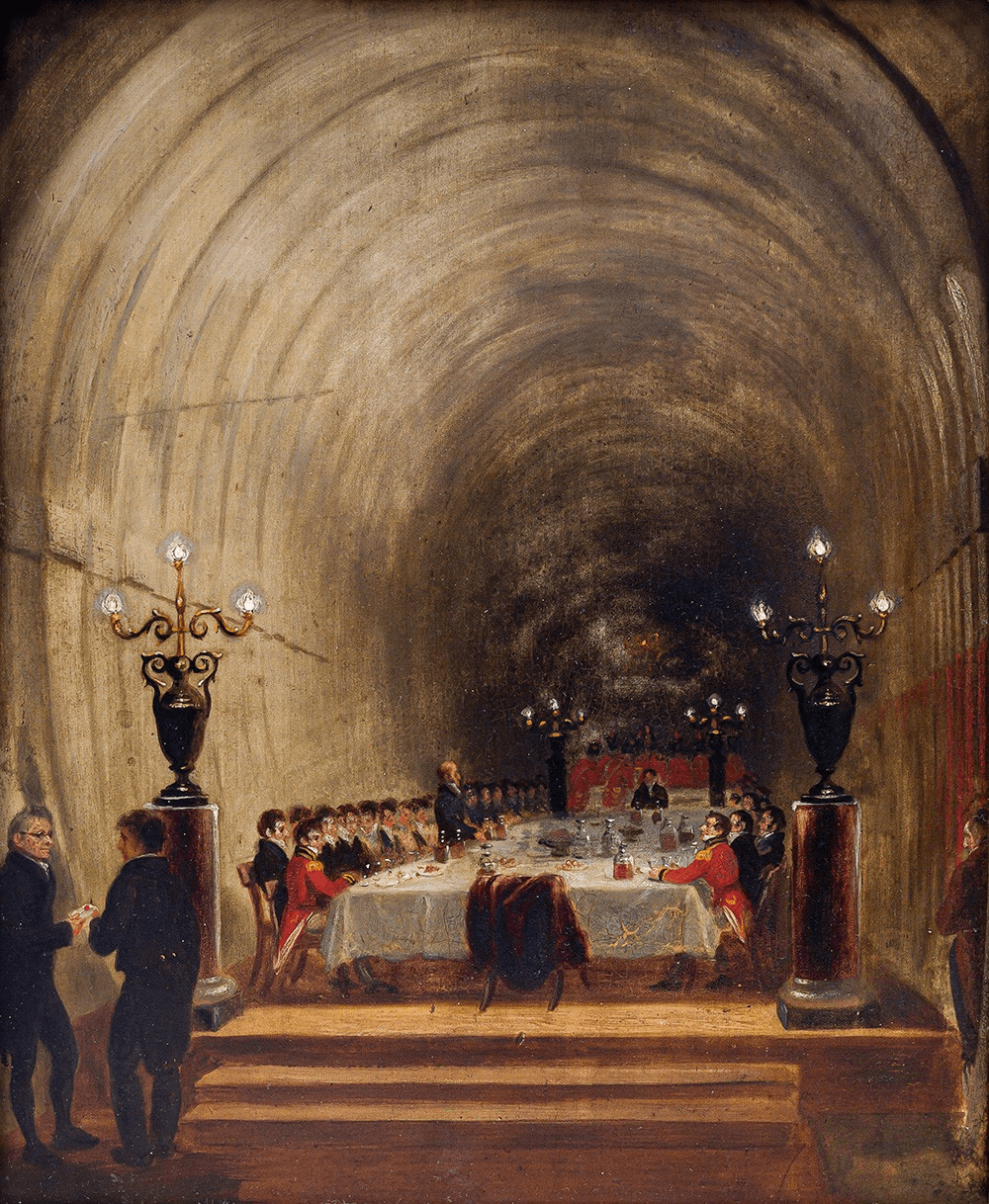

Despite its commercial failure, the Thames Tunnel was a sensation. It became a major tourist attraction, attracting about two million people a year, each paying a penny to pass through, and became the subject of popular songs. The American traveller William Allen Drew commented that “No one goes to London without visiting the Tunnel” and described it as the “eighth wonder of the world”. The tunnel’s interior became an underground bazaar, with vendors selling souvenirs and refreshments in the twin archways.

In 1869, the tunnel found new life when it was converted for use by the East London Railway, and since 2010, is part of the London Overground railway network. Today, thousands of commuters pass through Brunel’s tunnel daily, most unaware they’re travelling through a piece of history that changed engineering forever.

The Forgotten Pioneer: Tower Subway (1869-1870)

If Brunel’s tunnel proved underwater crossings were possible, the Tower Subway demonstrated they could be built quickly and (relatively) cheaply. Tower Subway was built in 1869 and stretches for 410 meters or 1,340 feet under the River Thames, running between Tower Hill and Vine Lane (modern-day Bermondsey).

This tunnel has several claims to fame. Arguably London’s first Tube railway, the Tower Subway was dug in 1870 two decades before the first sections of the Tube network proper. It was also the first tunnel to be constructed using the new cylindrical iron tunnelling shield developed by James Henry Greathead, an improvement on Brunel’s rectangular design that would become the standard for future tunnel construction.

Work on the tunnel began on February 16th, 1869, and by February 1870, the first passengers were using the tunnel—a remarkable achievement compared to the Thames Tunnel’s 18-year construction. Initially, a 2 feet 6 inch narrow gauge railway was put in the tunnel so that a cable-hauled wooden carriage transported passengers underneath the Thames.

However, the Tower Subway was a commercial disaster. The first-of-its-kind shuttle service only operated for around 3 months before its company went into receivership. The tunnel was converted to pedestrian use, with a halfpenny toll, and became popular with workers. When Tower Bridge opened in 1894, the foot tunnel became redundant.

Since then it has been used for cables and pipes, and no public access has ever been granted. You can still admire the northern entrance—a drum-shaped building standing, appropriately, outside Subway. The tunnel remains in use today for water mains and telecommunications cables, a Victorian achievement still serving modern London.

The People’s Crossings: Greenwich and Woolwich Foot Tunnels

At the dawn of the 20th century, London’s docks were booming, but thousands of workers living south of the river faced daily struggles crossing to their jobs in the northern docks. The answer came in the form of two foot tunnels that remain beloved features of London life today.

Greenwich Foot Tunnel (1902)

The Greenwich Foot Tunnel was the first of the pair, designed by Sir Alexander Binnie, who also designed the first Blackwall Tunnel and Vauxhall Bridge. The tunnel was desperately needed—the ferry service it replaced was unreliable, especially in fog, leaving dock workers stranded.

The tunnel opened on the Bank Holiday of 4 August 1902, measuring 1,217 feet in length, and about 50 feet deep. The twin glazed dome entrances at each end—one by the Cutty Sark in Greenwich, the other at Island Gardens on the Isle of Dogs—have become iconic London landmarks. The Greenwich Foot Tunnel cost £127,000 (about £15 million today), which included £30,000 compensation to the London watermen (about £3 million), who had lost their livelihoods.

Today, approximately 4,000 people use the tunnel each day, walking beneath the Thames to enjoy the famous “Canaletto view” of Greenwich from Island Gardens or commuting between south and north London.

Woolwich Foot Tunnel (1912)

A decade later, the Woolwich Foot Tunnel followed, designed by Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice and opened by Lord Cheylesmore, Chairman of the LCC, on Saturday, 26 October 1912. The creation of this tunnel owed much to working-class politician Will Crooks, who had worked in the docks and, after chairing the LCC’s Bridges Committee responsible for the tunnel, would later serve as Labour MP for Woolwich.

At 504 metres (1,654 ft) long, the Woolwich tunnel is longer than Greenwich, and at its deepest, the tunnel roof is about 3 metres (9.8 ft) below the river bed. Unlike Greenwich, which replaced its ferry service, the Woolwich tunnel was designed to complement the Woolwich Free Ferry, which continues operating today.

Both tunnels share certain characteristics that make them unique. They’re open 24/7, free to use, and officially, cyclists must dismount and walk their bikes through (though this rule is frequently flouted, to the frustration of pedestrians). The tunnels underwent major refurbishment between 2010 and 2014, with new lifts, CCTV, and drainage systems installed. In 2016 the Ethos Active Mobility system was installed in the tunnel to monitor and actively manage tunnel usage, using electronic signs to encourage considerate behavior.

These foot tunnels have become more than just river crossings—they’re part of London’s character. Ghost stories abound, particularly in Greenwich, where Victorian figures are said to walk the tunnel at night. During World War II, when a bomb damaged the Greenwich tunnel and flooded it, a ferry service had to be reinstated until repairs were completed after the war.

The Motor Age: Rotherhithe and Blackwall Tunnels

As the 20th century progressed and motor vehicles became common, London needed tunnels that could handle cars and lorries, not just pedestrians and trains. The engineering challenges were immense—these tunnels needed to be larger, better ventilated, and capable of handling the weight and vibration of heavy traffic.

Rotherhithe Tunnel (1908)

The Rotherhithe Tunnel, opened in 1908, was London’s first tunnel designed specifically for road vehicles, though horses and carts were the primary users initially. Designed by Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice (who would later design the Woolwich Foot Tunnel), it runs for 1.48 miles between Rotherhithe and Limehouse.

This is the most westerly place in London where you can drive your motor under the Thames. It is also the only tunnel under the Thames through which cycling is permitted (though not many brave the fumes). The tunnel remains the only free road tunnel under the Thames in central London and the only one with two-way traffic—a somewhat terrifying experience given its narrow bore and poor ventilation.

Blackwall Tunnels (1897 & 1967)

The Blackwall Tunnel actually comprises two separate tunnels built 70 years apart. The original northbound tunnel opened in 1897, designed by Sir Alexander Binnie (who also designed the Greenwich Foot Tunnel). It was a marvel of Victorian engineering but quickly proved inadequate for modern traffic. The tunnel has a notorious sharp bend (necessitated by the need to avoid the dock entrances above) and height restrictions that regularly catch out unwary lorry drivers.

The second, southbound tunnel opened in 1967, built to modern standards with better ventilation and a straighter alignment. Actually two separate one-way tunnels, spaced quite far apart, and opened 70 years apart, they handle a combined load of over 100,000 vehicles daily, making them among the busiest river crossings in London.

The Modern Era: Jubilee Line and Beyond

The late 20th century saw a new wave of tunnel construction as London’s transport needs evolved. The Jubilee Line Extension, completed in 1999, added four crossings beneath the river, using modern tunnel boring machines (TBMs) that would have amazed Brunel. These massive machines, often named after female historical figures or project workers, can bore through London clay while simultaneously installing the tunnel lining.

Only five of the 11 tube lines pass beneath the river: Victoria, Northern (twice), Bakerloo, Jubilee (four times) and the Waterloo & City lines. The newest addition to London’s rail network, the Elizabeth Line (Crossrail), added another crossing between North Woolwich and Woolwich, finally giving Southeast London a high-capacity rail link to the city center and beyond.

The 21st Century: Silvertown and the Super Sewer

Silvertown Tunnel (2025)

After decades of planning and five years of construction, the Silvertown Tunnel opened to traffic in the early hours of 7 April 2025. This 1.4-kilometer twin-bore tunnel runs between west Silvertown and the Greenwich Peninsula, built to relieve chronic congestion at the nearby Blackwall Tunnel.

The project used a massive 11.87-meter diameter tunnel boring machine named “Jill” after Jill Viner, the first female bus driver in London. Tunnelling began in September 2022, with the southbound tunnel drive completed on 15 February 2023 and the northbound tunnel completed on 4 September 2023.

The Silvertown Tunnel represents a new approach to Thames crossings. For the first time, a toll system has been introduced not just for the new tunnel but also for the adjacent Blackwall Tunnel, using automatic number plate recognition to manage traffic flow and fund the construction. The tunnel includes dedicated bus lanes and a cycle shuttle service, acknowledging that simply building more road capacity isn’t sustainable for London’s future.

Controversially, on 25 April 2025, approximately 1,000 cyclists staged a mass trespass in the Silvertown Tunnel as part of a Critical Mass ride, temporarily halting traffic, protesting the lack of cycling infrastructure in the new tunnel.

Thames Tideway Tunnel (2025)

Perhaps the most ambitious current project is the Thames Tideway Tunnel, known as the “super sewer.” This £4.5 billion project is a 25km tunnel running from west to east London, largely under the route of the River Thames. The tunnel measures at 7.2m wide (the width of three London buses) and is up to 67m deep.

This tunnel addresses a problem as old as London’s sewer system itself. When Joseph Bazalgette built London’s sewers in the 1860s, they were designed to overflow into the Thames during heavy rain—acceptable when London’s population was 3 million, but catastrophic now that it exceeds 9 million. The new tunnel operates with the sewage treatment works and the Lee Tunnel. Together this new combined system has a combined capacity of 1.6m m³ to protect the River Thames in London.

Tideway have now started switching on the first of the sites. This means the new tunnel has started to protect the River Thames from sewage pollution. When fully operational, it will capture 95% of the sewage that currently overflows into the Thames, dramatically improving river quality.

The Secret World Below

Beyond the tunnels we can use or see, London harbors a secret network of passages beneath the Thames. Besides the public tunnels listed above, numerous inaccessible tunnels span the Thames. These include utility tunnels carrying electricity, gas, water, and telecommunications cables—the invisible infrastructure that keeps London functioning.

Some tunnels have been repurposed multiple times. The Tower Subway, for instance, now carries water mains and cables. Others have been abandoned or sealed—ghost tunnels that exist only in archives and the memories of engineers.

There are persistent rumors of government and military tunnels, though their existence is neither confirmed nor denied. What is certain is that the network beneath the Thames is far more extensive than most Londoners realize.

Engineering Evolution: From Shields to TBMs

The story of Thames tunnels is also the story of tunnelling technology. Brunel’s rectangular shield, revolutionary in 1825, gave way to Greathead’s circular shield in 1869. The 20th century brought compressed air working (to prevent water ingress), and concrete segments replaced brick lining.

Modern tunnel boring machines are marvels of engineering. The TBM used for Silvertown Tunnel could bore through London clay while simultaneously installing precast concrete tunnel segments, maintaining precise alignment through GPS and laser guidance systems. These machines can cost tens of millions of pounds but can complete in months what once took years.

Yet even with modern technology, London’s geology presents challenges. The London clay that makes tunnelling possible also contains pockets of gravel and sand that can cause instability. The Thames itself adds pressure and the risk of flooding. Every tunnel under the Thames is a victory over these natural forces.

Looking Forward: The Future of Thames Crossings

As London continues to grow, the debate over new Thames crossings intensifies. Proposals for new tunnels compete with demands for bridges, while others argue that London needs better public transport, not more road capacity. The Silvertown Tunnel’s controversial toll system may provide a template for future crossings—using pricing to manage demand rather than simply building more infrastructure.

Climate change adds urgency to these discussions. Rising river levels and increased rainfall will test existing tunnels, particularly the Victorian-era passages. The Thames Tideway Tunnel shows how infrastructure must adapt to environmental challenges.

There are also dreams of new types of crossing. Proposals for pedestrian and cycle tunnels have been floated, learning from cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam. Some suggest repurposing abandoned tunnels for new uses—turning Victorian engineering into 21st-century assets.

Conclusion: The Hidden History Beneath Our Feet

From Brunel’s revolutionary shield to the massive boring machines of today, the tunnels under the Thames tell the story of London’s growth, ambition, and ingenuity. Each tunnel represents not just an engineering achievement but a response to the city’s evolving needs—from dock workers needing to reach their jobs to modern Londoners demanding cleaner rivers and sustainable transport.

These tunnels have shaped London in ways both obvious and subtle. They’ve determined where people live and work, influenced property prices, and created new communities while dividing others. They’ve been tourist attractions and air raid shelters, commercial failures and vital arteries.

Today, millions of Londoners pass beneath the Thames without a second thought, taking for granted what was once considered impossible. Yet each journey through these tunnels is a voyage through history, from the Victorian ambition of Brunel’s tunnel to the environmental consciousness of the super sewer.

As London faces the challenges of the 21st century—population growth, climate change, air pollution—its tunnels will continue to evolve. New crossings will be built, old ones will be reimagined, and the network beneath the Thames will grow ever more complex. But the fundamental challenge remains the same as it was in Brunel’s day: how to unite a city divided by its greatest natural feature.

The next time you descend into one of London’s Thames tunnels—whether on the Tube, in a car, or on foot—take a moment to consider the engineering marvels surrounding you. Beneath the Thames lies not just a network of tunnels but a testament to human ingenuity, persistence, and the never-ending quest to overcome nature’s barriers. In these dark passages under London’s ancient river, we find illumination about who we are and what we can achieve when we dare to dig deep.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!