KEY FACTS

- Designed by Harry Beck in 1932

- Set a style for transport maps around the world

- As instantly recognisable as the Union Jack

- Beck received little credit for his work during his lifetime

London’s history is filled with historical figures who were just doing a job or once had an idea that turned into something bigger than they ever intended. Henry C Beck was a simple draftsman who thought the London Underground’s Tube map was too complicated and could be easier to understand if it looked more like an electrical diagram. This led to a global standard that most transport networks now follow. Despite this, there was a fight to get credit for his creation from London Transport.

The London Underground railway system, always referred to as “The Tube,” was the world’s first such system and began with the opening in 1863 of the Metropolitan Line. The train was pulled through the tunnels by a steam engine fuelled with coal, and the carriages were lit by gas lights. The system was intended for transporting workers, and indeed, with all the smoke and ash filling the tunnels and the stations, few other people were willing to use the early trains. Nonetheless, other lines soon followed, with the District and the Circle Lines by 1884. These early lines were shallow, vented by shafts in the walls extending to the surface, which can still be seen at Baker Street station, and extended up to 50 miles out into the countryside, where much of the working-class lived.

Fully underground lines with electric trains began in 1890 with the City and South London Line, and by the early 20th century an extensive network of different companies, linked by marketing agreements, ran the system. During WWI, and again in WWII, the stations were used as underground shelters against bombing raids. After WWI, with government funding and support, the system was further expanded, and in 1933 all the underground trains and the above-ground bus and tram services were merged into the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). Following the election of the Labour government after WWII on a platform of nationalisation of industry, the LPTB was nationalised.

In the early days of the system, each separate company printed a map of its own line showing the various stations. But in 1908, under the early marketing agreements that were made, a joint map was published, and at the same time the ‘UNDERGROUND’ term was promoted and displayed prominently across the top of the early maps. These first maps were geographically accurate, showing streets and other features. As a result showing enough detail for the central area meant leaving outlying sections of the lines of the map completely. Leslie MacDonald Gill was a cartographer and graphic designer, connected through his brother to the Arts and Crafts Movement. In 1913, he produced a map of the system in a humorous style, called the Wunderground Map, which hung in all the stations. His style of combining accuracy with cartoon-style illustrations is still seen today on many maps.

Max, as he was known, abandoned geographic accuracy for clarity and entertainment, but simultaneously much more sparse maps, showing just the stations on a straight line, were being produced and displayed in stations and on platforms. These were drawn by George Dow, employed by the London and North Eastern Railway and a railway historian in his own right.

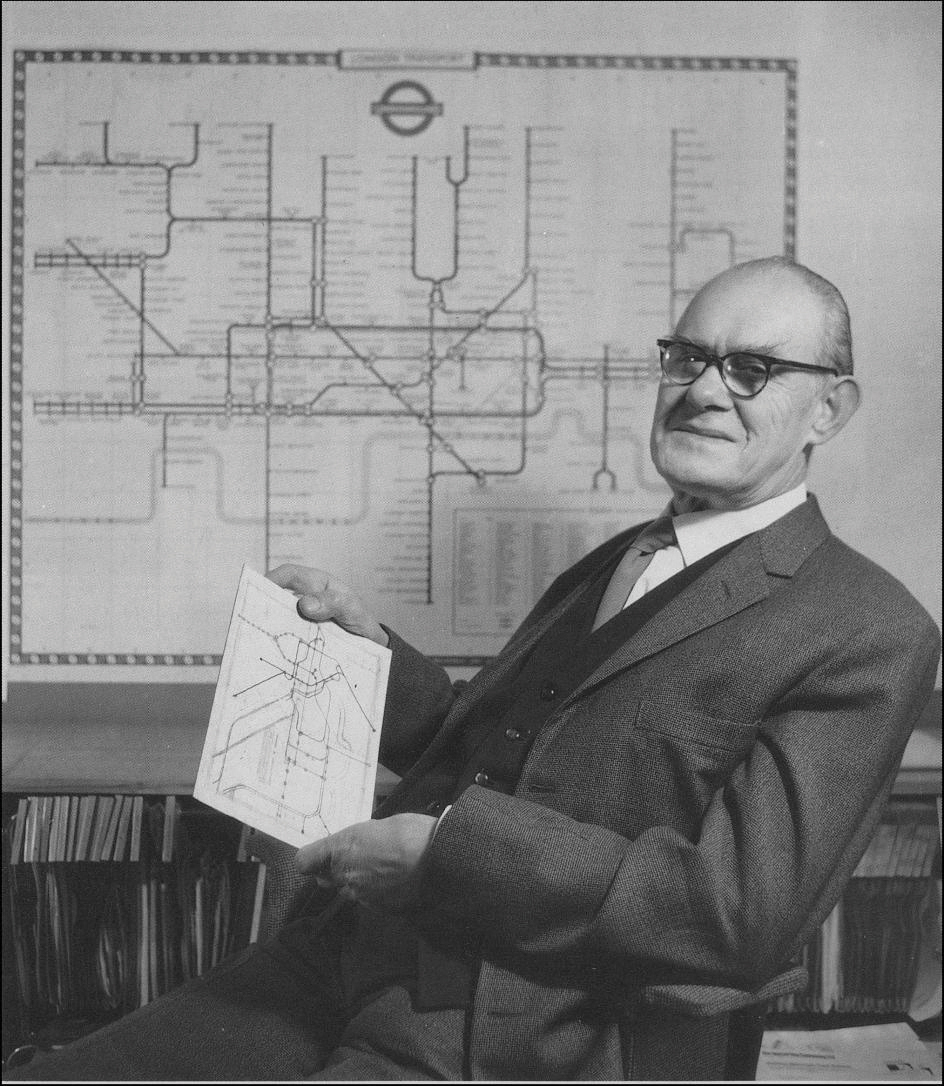

Around 1930, an engineering draftsman at the London Underground Signals Office, called Henry Charles Beck, or more often simply ‘Harry,’ sat down in his spare time and devised a linear plan of the whole system, showing the interrelationships, but not the actual positions, of the underground stations and lines. His direct inspiration was the electrical circuit diagrams he was working on, which simply showed connections, without any scale. Many people also believe he was influenced by Max’s linear diagrams of the individual lines and Gill’s introduction of graphics.

Believing that he was correct in thinking that people only wanted to know where the stations were, and where to change lines, Beck approached Frank Pick, an executive at London Underground, who was the person who commissioned Max Gill’s Wunderground map. Pick, and others were skeptical, but Beck persisted, and a trial printing of 500 maps appeared at a few stations in 1932. This was also to become the last year that the previous geographic maps, at this period being designed by F. H. Stingemore, were to appear. Beck had done all his work in his own time and was paid 15 guineas for the artwork of the pamphlet and poster forms of his design. A guinea was a sum equivalent to one pound plus one shilling (one-20th of a pound), and Beck’s 15guineas would be worth between one and five thousand pounds today, depending on the conversion system used. There is some dispute as to whether in fact any payment was made at all.

Beck’s new map proved an instant hit with the commuting public and 700,000 copies were printed and distributed throughout the system in 1933. That first printing was gone within a month, and much larger reprints quickly followed. For some time, Beck was employed on a freelance basis to update and amend the map, but in 1960 London Transport used an employee, Harold Hutchinson, to add the new Victoria Line to the map and began making other changes without consulting Beck. His name as the designer was removed from the bottom of the map. Five years of legal struggle followed as Beck tried to get control of the map back, but when his wife’s mental health began to suffer Beck withdrew from the battle, defeated.

Beck had left London Underground in 1947 and eked out a living as a freelance designer and teacher until his death in 1974. He continued to make changes to his original design and submit them to London Transport, only to have them rejected. He continued to privately make modifications and sketches for the rest of his life.

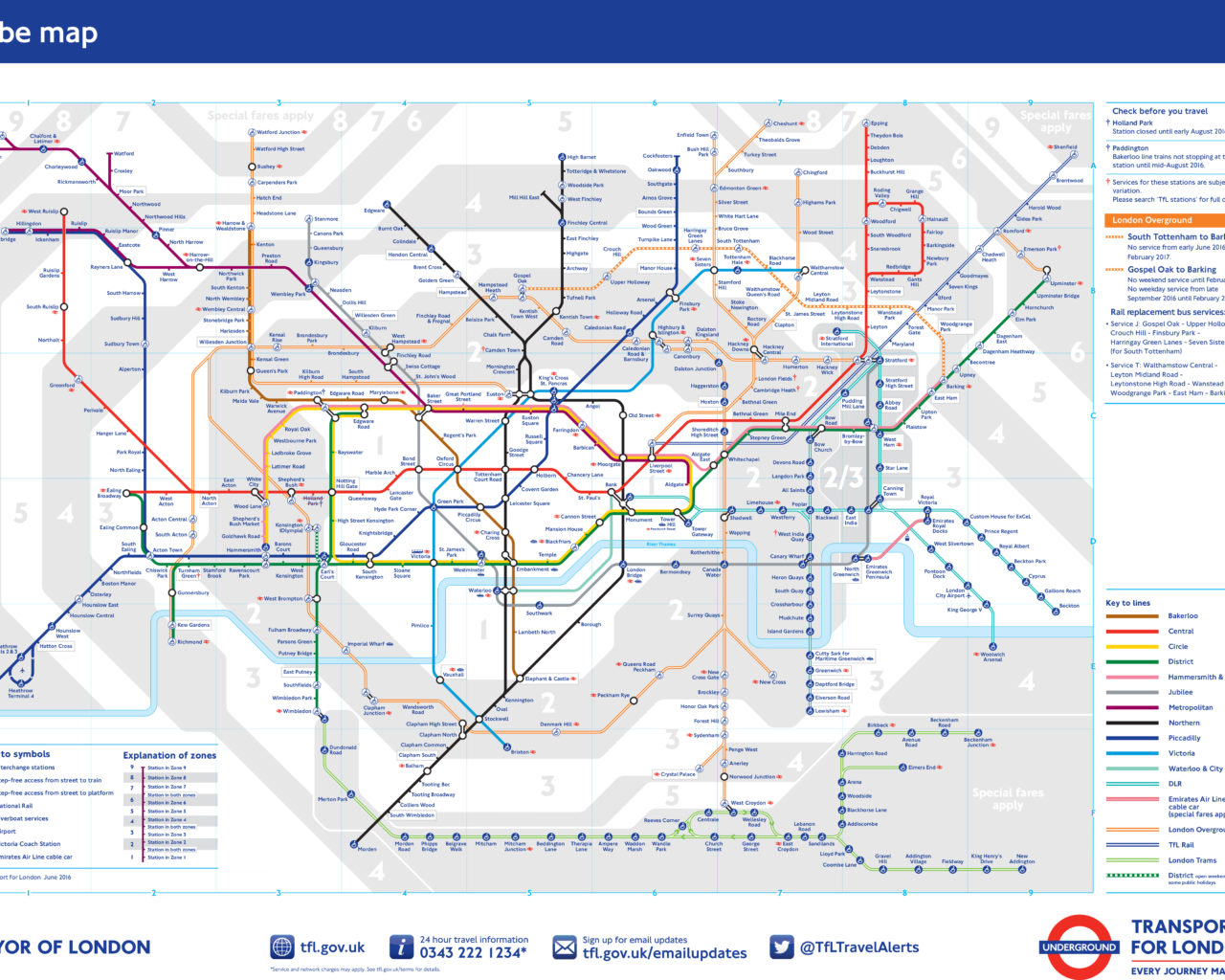

Following the split with Beck, a new designer, Paul Garbutt, was employed to update the map. He is responsible for the familiar ‘flask’ shape of the Central Line. Garbutt had actually produced his first version privately and presented it to London Underground, as he found the Hutchinson map so bad. Beck was much more sympathetic to Garbutt’s design. It was Garbutt who carried the map into its modern version, working on it for 20 years. Later maps added features such as the surface rail and light-rail systems of the city, and in 2002 when a fare system using zones was introduced, these were added to the map too.

In 1997, Beck’s reputation was rehabilitated, and his name now appears again on all Underground maps, as the original conceiver of the map. His map has been voted second-favourite British design, after Concorde. The style of design has been copied by railway and underground systems worldwide. The irony is that the modern Tube Map (pictured left) has now become confusing again with the addition of the new London Overground and other new lines.

Sites to Visit and Further Research

Beck’s work on this and other maps can be seen in the Beck Gallery at the London Transport Museum, in the Covent Garden Piazza, WC2E. The Museum is open until 6 p.m. every day and is well worth a visit for anyone interested in London’s fascinating transport history.

There is a blue plaque on the house where Beck was born, 14 Wesley Road, Leyton, E10. The nearest Tube stop is Leyton Station, on the Central Line.

There is a commemorative plaque to Beck, and an early design by him, at Finchley Central Tube station.