Editor’s Note: You’re going to want to brew a cuppa and read this one!

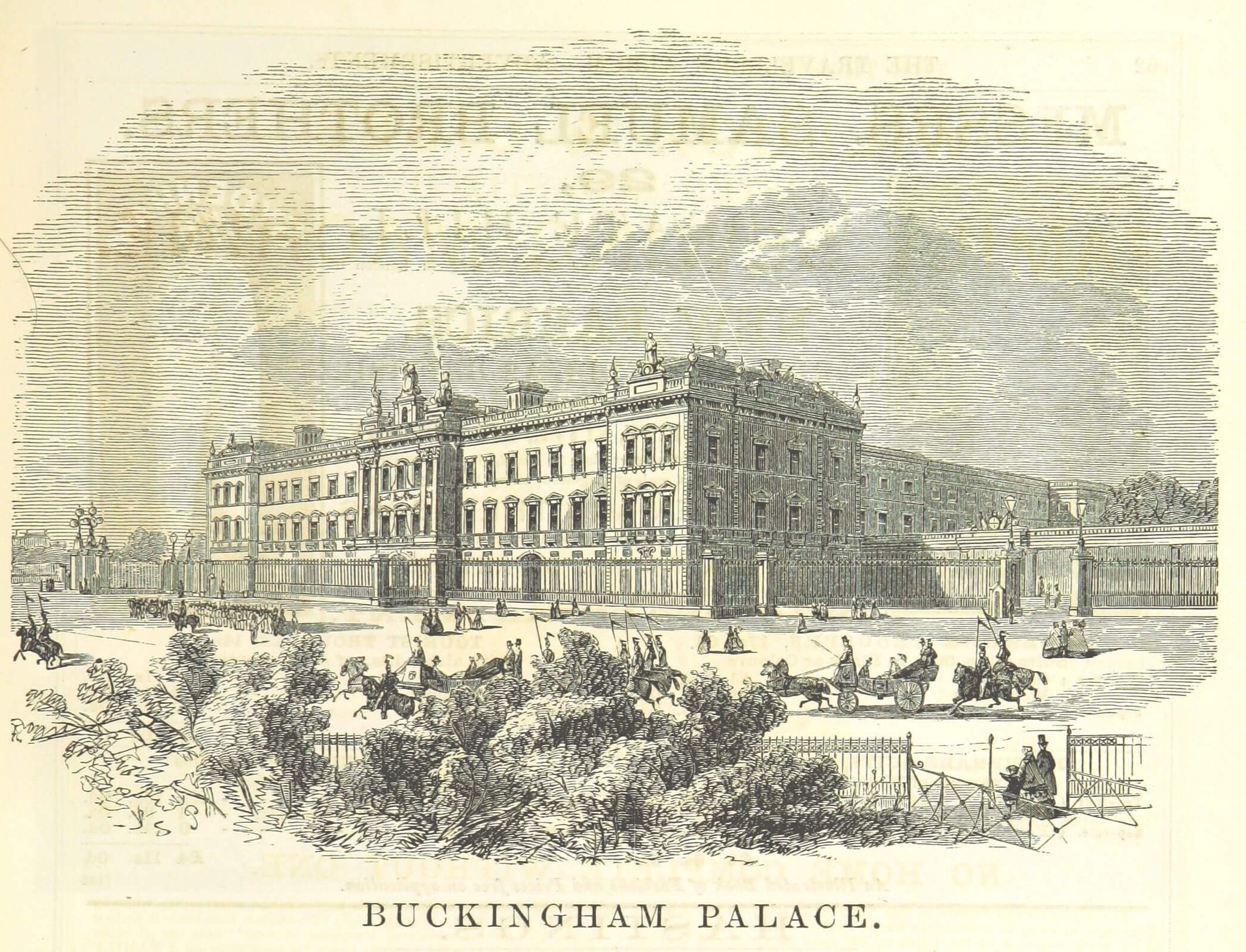

While it has a much longer history, Buckingham Palace only became the London residence of Britain’s sovereigns in 1837. The Palace is the administrative headquarters of the monarchy and the royal family. (The Queen refers to Buckingham Palace as “the office” as it’s where she works rather than relaxes.)

The 830,000 sq. ft. building has 775 rooms including 19 staterooms, 52 royal and guest bedrooms, 188 staff bedrooms, 92 offices and 78 bathrooms. It also has its own post office, cinema, swimming pool, doctor’s surgery and jeweller’s workshop. But the building we see today is the product of many years’ extending and remodelling, with varying degrees of success.

The palace garden, with its tranquil lake, is the largest private garden in London. It covers 40 acres (16 ha) and includes a helicopter landing area and a tennis court.

Derks24 / PixabayBut the site has a long history so let’s have a look at what was here before and how the building we can see today came about.

Pre-1500s

In the Middle Ages (5th to late 15th century), the site of the future palace formed part of the Manor of Ebury (also called Eia). The marshy ground was watered by the river Tyburn, which still flows below Buckingham Palace courtyard and the south wing of the Palace.

Ownership of the site changed hands many times. Edward the Confessor (ruled 1042–1066) and his queen consort Edith of Wessex had the land in late Saxon times. After the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror (reigned 1066–1087) gave the site to Geoffrey de Mandeville, who bequeathed it to the monks of Westminster Abbey. De Mandeville was the Norman Constable of the Tower of London (the most senior role).

The 1500s

When Henry VIII decided to seek a papal annulment from his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he expected his advisor, Cardinal Wolsey, to petition Pope Clement VII. As we know, Henry didn’t get his own way, and that was because of pressure on the Pope from Catherine’s nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Wolsey was forced from power for his failure and died in 1530 awaiting trial for treason. So that is how Henry VIII settled in Cardinal Wolsey’s Whitehall Palace in 1530. (All that remains is Banqueting House on Whitehall.) In 1533, Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in a private chapel at Whitehall Palace in a secret ceremony.

Soon after moving to the area, he acquired the Hospital of St James (a leper hospital) from Eton College. He commissioned a new palace and St James’s Palace was built by 1536. The same year he took the Manor of Ebury from Westminster Abbey. (The English Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries meant the King could take what he wanted from the Catholic church.) This brought the site of Buckingham Palace back into royal hands for the first time since William the Conqueror had given it away almost 500 years earlier.

Henry VIII improved the area by draining the marshy land to create St James’s Park as an enclosed private hunting park that stretched from Kensington to Westminster – the area we now know as Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. The royal hunts were grand and extravagant occasions attended by the glitterati of the day. Visitors watched from grandstands and enjoyed great feasts in temporary banqueting houses.

From the River Tyburn that ran through Green Park, he created the lakes that now adorn the grounds of Buckingham Palace and St James’s Park.

Early 1600s

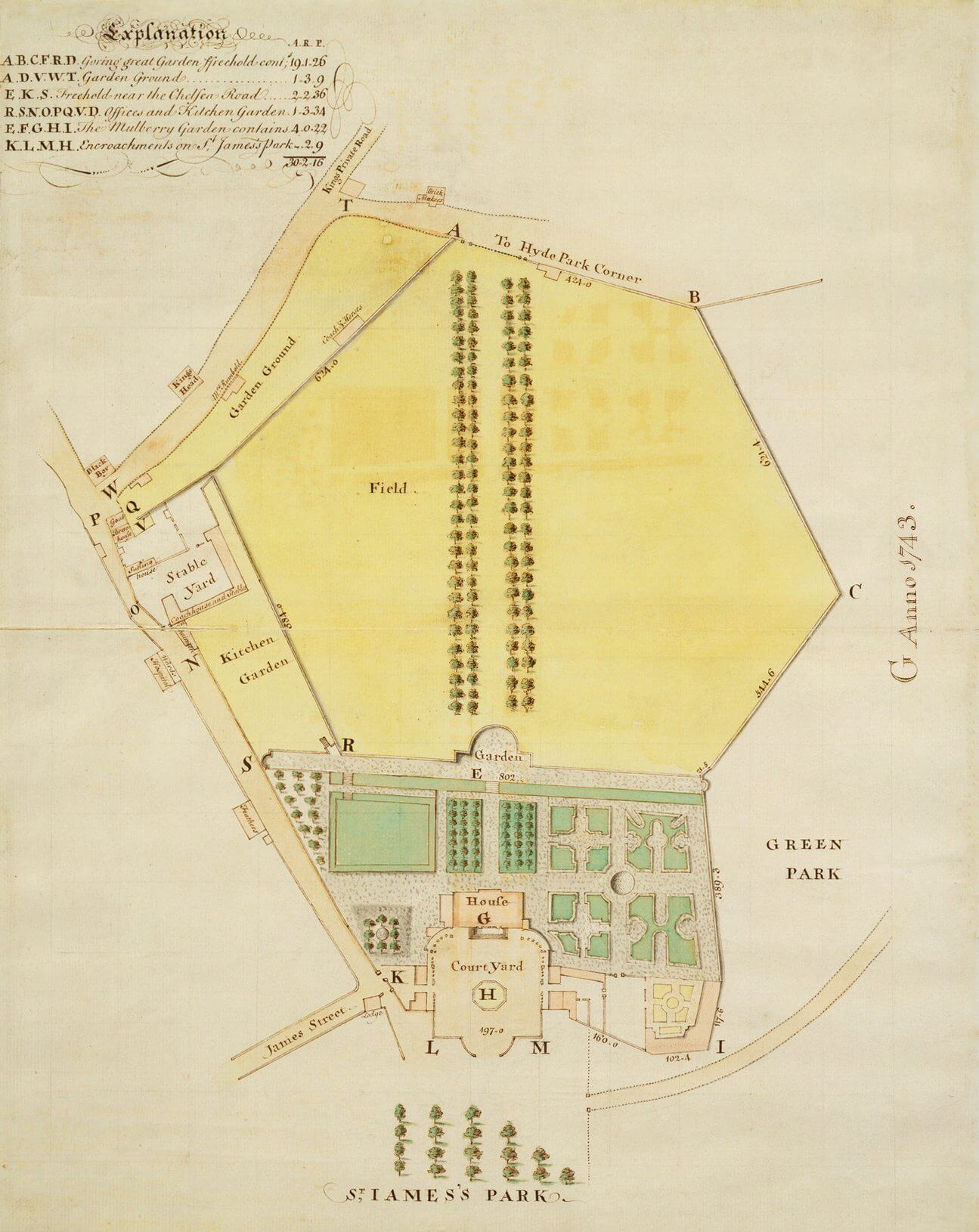

Needing money, James I sold off some of the Crown freehold but retained part of the site on which he established a 4-acre (1.6 ha) mulberry garden for the production of silk in England. (This is at the north-west corner of today’s palace.)

James I (he was King of Scotland as James VI and King of England and Ireland as James I) had been envious of France’s prowess as a producer of the luxurious silk that dominated 17th-century fashion. Keen to encourage silk production in London, the mulberry trees were for the silkworms to feed upon.

Sadly, his plan didn’t work as he planted the wrong type of mulberry tree so the silkworms could only produce a coarse thread. But a collection of mulberry trees were planted in Buckingham Palace garden in 2001 to remember the earlier land use.

1620–1640

It is thought the first house to be erected on the site was for Sir William Blake in around 1624. Charles I gave the garden to Lord Aston in 1628, and it is clear from records that a large house already existed on the site at this time.

The next owner was George, Lord Goring (1608–57) who had purchased it from Aston’s son. From 1633 to 1640, he extended Blake’s house to create Goring House. He built a ‘fair house and other convenient buildings and outhouses, and upon other part of it made the ffountaine garden, a Tarris [terrace] walke, a Court Yard, and laundry yard’. He also developed much of today’s garden, then known as Goring Great Garden.

He did not, however, obtain the freehold interest in the mulberry garden. Unbeknown to Goring, in 1640 the document “failed to pass the Great Seal before King Charles I fled London, which it needed to do for legal execution”. It was this critical omission that helped the British royal family regain the freehold under King George III.

1660–1697

When Lord Goring defaulted on his rents, Henry Bennet (1618–85), Charles II’s Secretary of State and later Earl of Arlington was able to purchase the lease of Goring House. He was occupying it when it burned down in September 1674. John Evelyn recorded, ‘exceeding losse of hangings, plate, rare pictures and Cabinets’.

The following year, Arlington started the rebuild on the location of the southern wing of today’s palace. He chose a design which appears to have been in the new style of the time, perfected by architects such as Roger Pratt and Hugh May.

Lord Arlington was able to exploit the newly created axial features of St James’s Park, laid out for Charles II by the French royal gardener André Mollet to embellish the settings of the palaces of Whitehall and St James’s. These were the long double avenue along the southern edge of St James’s Palace, on the line of The Mall, and the long canal extending from Horse Guards to the western edge of St James’s Park, itself lined with double avenues. (Do zoom in on this 1682 London map to see the area on the middle left.)

Despite the grandeur of its setting, or perhaps because the new avenue made the site so very fashionable and exclusive, Arlington House lasted only twenty-five years.

1698

After his first wife died the year before, in 1698 poet and Tory politician John Sheffield, later the first Duke of Buckingham and Normanby (third Duke of Buckingham), acquired a short lease on the house. (The Duke’s family descended from Sir Edmund Sheffield, a second cousin of Henry VIII.) The following year he acquired the house outright (or so he thought), and recognising its increasingly dated appearance in an acutely fashion-conscious age, demolished it.

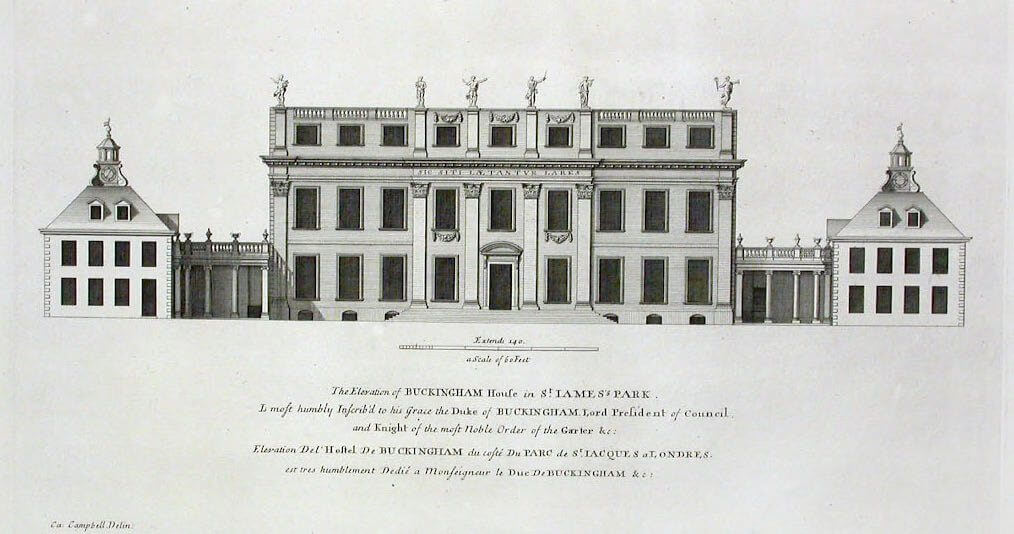

The new building became Buckingham House, and its essential plan and the layout of its forecourt dictated all subsequent buildings including the current Buckingham Palace. The first designs were probably prepared by William Talman (1650–1719), Comptroller of the Works to William III. He was also the architect of the interior of the king’s new apartments at Hampton Court Palace and of Chatsworth House – considered to be the first baroque private house in Britain.

It seems that Talman and Sheffield had a disagreement and Captain William Winde, a retired soldier, took over the design. John Fitch built the main structure by contract for £7,000.

Buckingham House was a large austere red-brick townhouse. It had three storeys in a central block with two smaller flanking service wings. The best contemporary artists and craftsmen were employed, including mural painters and sculptors, and it was generally deemed the finest house in London.

John Sheffield (1648–1721), 3rd Earl of Mulgrave and Marquess of Normanby, became the Duke of Buckingham in 1703. The same year that Buckingham House was completed.

He had married his second wife in 1698, but she died young in 1703. The Duke then married his third wife in 1705. Lady Catherine Darnley (1680–1743) was an illegitimate daughter of King James II and Catherine Sedley (the King’s mistress before and after he came to the throne). They had three sons of whom Edmund survived and succeeded him as 2nd Duke of Buckingham (he died unmarried in 1735 when all his titles became extinct).

1731–1775

The Duke of Buckingham died in 1731, and George II approached the Duke’s widow with an offer to buy Buckingham House. He wasn’t successful.

The Duchess of Buckingham remained there until she died in 1742. The house was then in the hands of the Duke’s illegitimate son, Sir Charles Sheffield.

After George II died in 1760, his son, George III (reigned 1760–1820), became King of Great Britain and Ireland. In 1761, John, 3rd Earl of Bute, George III’s mentor and advisor, began to engineer the purchase of Buckingham House for the King. He discovered that in the Duke’s ambition to build what amounted to a private palace, he had unwittingly encroached on the former royal mulberry garden. Sir Charles Sheffield was obliged to part with the house for under £30,000 in 1762.

King George III married Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in September 1761. While the wedding ceremony was at St James’s Palace, the king wanted to have “a retreat” so Buckingham House was to be the family home and St James’s Palace was maintained as the official seat of the court.

Between 1762 and 1776 the house was transformed inside and out at a cost of £73,000. Sir William Chambers was put in charge of remodelling and modernising the house. With ceilings designed by Robert Adam and painted by Giovanni Battista Cipriani. The Queen’s rooms on the principal floor were among the most sophisticated of their time. And the King, one of the greatest book collectors in the history of England, created a fine library in the house which we can now see in the British Library.

George gave Buckingham House to Queen Charlotte in 1775 as a private family residence. An Act of Parliament settled the property on Queen Charlotte in exchange for her rights to Somerset House. The building became known as The Queen’s House from then on. Fourteen of George and Charlotte’s fifteen children were born there.

Some furnishings were transferred from Carlton House, and others had been bought in France after the French Revolution of 1789.

While St James’s Palace remained the official and ceremonial royal residence, the name “Buckingham-palace” was used from at least 1791.

George III spent his twilight years at Windsor Castle, suffering from the effects of his porphyria.

1820–1829

George III died in 1820. The king’s son, George IV (1762-1830) was almost 60 when he took the throne and already in poor health. He had grown up in Buckingham House so was fond of the building. George IV was the first monarch to see palace potential in Buckingham House.

When George IV was the Prince Regent, he had commissioned the architect John Nash to design Regent Street and Piccadilly Circus (1809–1826) and Regent’s Park (1809–1832). He also re-landscaped St. James’s Park (1814–1827) reshaping the formal canal into the present lake. Nash also redesigned the Brighton Pavilion for George IV in 1815–1822. The Royal Pavilion at Brighton is a remarkable testament to the wide-ranging decorative tastes of George IV when Prince Regent (1811–1820).

In his coronation year (1821), the famously extravagant King instructed John Nash, Official Architect to the Office of Woods and Forests, to refurbish the state apartments at St James’s Palace for the use of the new King. These works were completed in 1824 at a cost of £60,000.

Also in 1821, Nash was charged by the Board of Works to relocate the King’s Mews at Charing Cross to a new stable complex adjacent to Buckingham House. This became the Royal Mews incorporating stables and coach houses with living quarters above. (Nash went on to undertake the redevelopment of the area into Trafalgar Square which opened, much later due to his ill health, in 1844.)

While Nash was busy with the new Mews and state apartments at St James’s, little happened at Buckingham House. But in May 1825 Nash was instructed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer to prepare plans for the enlargement and modernisation of Buckingham House for approval by the King.

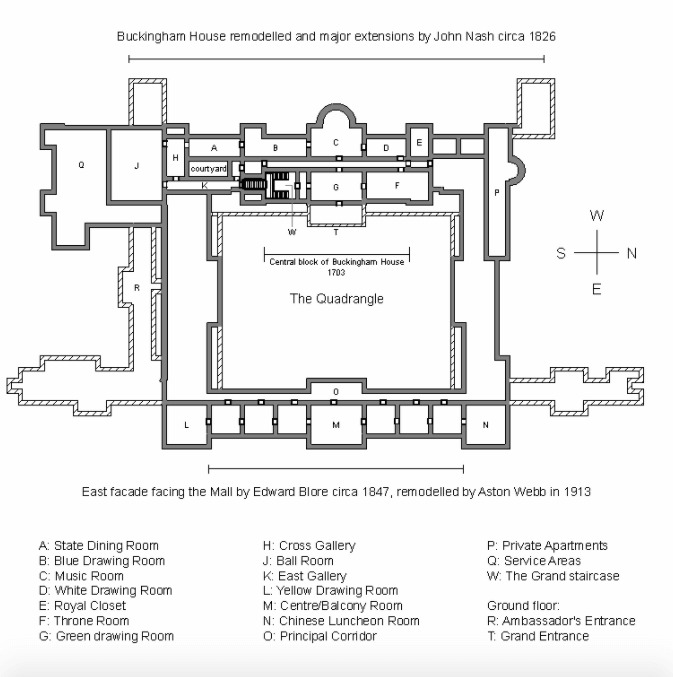

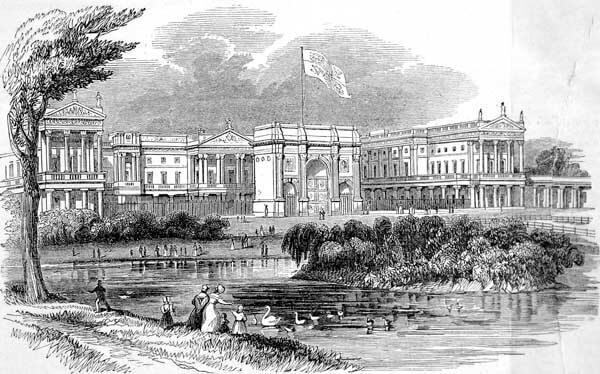

The plans submitted in 1826 involved constructing three wings around a central courtyard. The external façade was designed in the French neoclassical style that was favoured by the King. George IV continued his extravagance and persuaded Parliament to stretch the agreed renovation budget from £150,000 to £450,000.

Nash retained the core of the house which dictated the floor plan, ceiling height and proportions of many of the rooms. The central block was extended westwards, the north and south wings demolished and rebuilt, and the two wings to the east were rebuilt in much the same style as Nash deployed on the Regent’s Park terraces.

When first completed, the wings, enclosing a grand forecourt, were a single storey in height, rising to two storeys at their centres and three at their eastern ends. At the centre of the new East Front was a colossal double portico supporting a sculptural pediment. After criticism, the wings were rebuilt to the same height as the main block and terminated with pedimented porticos that referred back to the centrepiece of the main East Front. The building was faced with stone from the quarries near Bath.

A triumphal arch was added in 1827 to form part of a ceremonial processional approach for the state entrance to the cour d’honneur of Buckingham Palace. The Marble Arch stood near the site of what is today the three-bayed, central projection of the palace containing the well-known balcony. The whole arch is clad in Ravaccione, a grey/white type of Carrara marble from Italy. This was the first time marble had been used in this way on any British building. The arch was to be decorated with images depicting Britain’s recent military victories. The Marble Arch was completed in 1833 although the central gates were not added until 1837, just in time for Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne.

Although Nash’s work on the new palace was well received, and the building is still viewed as an architectural masterpiece today, Nash was dismissed soon after George IV’s death in 1830. Spending on the project had spiralled out of control. By 1829, the costs had crept up to half a million pounds. No sooner was the King dead than the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, intervened to ‘make a Hash of Nash’ and to call a halt to further expenditure. It should be noted the King never got to move in.

1830–1837

George IV’s brother, William IV (reigned 1830–1837) showed no interest in moving from his home at Clarence House.

The task of seeing the Palace through to completion fell to Lord Duncannon, First Commissioner of Works. Duncannon appointed a new architect, Edward Blore (1787–1879). Blore extended the east façade at both ends providing a guard room at the southern end and a matching screen at the northern end. Beyond the guard room to the west, Blore created a new approach called the Ambassador’s Entrance. (It’s where the public enter to visit the State Rooms.)

As the furnishing stage had not been reached at Buckingham Palace during George IV’s lifetime, parliament voted in 1833–34 to complete the furnishing and interior refurbishment of Buckingham Palace for use as the official royal home. The State Rooms were furnished with some of the finest objects from Carlton House, George IV’s London home when Prince of Wales, which had been demolished in 1827.

William IV still didn’t want to move in. When the Houses of Parliament was destroyed by fire in 1834, he offered Buckingham Palace as the new home of the legislature. The offer was respectfully declined, and Parliament voted to allow the ‘completing and perfecting’ of the Palace for royal use with a sum of £55,000.

By 1831, the year following George IV’s death, the final cost of the rebuilding was forecast at £696,353. And by the time the Palace became habitable at the beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria six years later, approximately £800,000 have been expended.

1837–1900

William IV took possession of Buckingham Palace on 5 May 1837, only a few weeks before he died. His niece, Victoria (reigned 1837–1901) was his successor, and she became the first royal resident of Buckingham Palace.

Within weeks of becoming the ruler of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 20 June 1837, 18-year-old Victoria adopted Buckingham Palace as her official residence. Victoria was raised at Kensington Palace under the strict ‘Kensington System’. It was supposed to prepare her for when she would be Queen, but the cruel regulations were also designed to break her spirit. She wasn’t even allowed to walk down the stairs unaccompanied, and she had to share a bedroom with her mother.

It was soon clear that the opulent interiors masked some serious shortcomings. The chimneys smoked so badly that the fires couldn’t be lit, leaving residents freezing. Many of the hundreds of windows couldn’t be opened. Few of the toilets were ventilated. The rooms constantly smelled musty, and there were fears that installing gas lighting would risk a build-up of gas on the lower floors. Soon after taking up residence in the new palace, Queen Victoria complained about the lack of space for entertaining foreign dignitaries. And it was also said that staff were lax and lazy, so the palace was dirty. She may have been Queen, but Victoria wasn’t getting the respect she deserved from the servants.

Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg in 1840, and she lived at Buckingham Palace with her expanding family until the Prince Consort’s death in 1861.

In 1845, eight years after ascending the throne, Queen Victoria complained to the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, about the lack of space in Buckingham Palace for accommodation and entertaining. (She already had four children and was pregnant with her fifth.) Edward Blore was instructed to prepare plans for a new wing, enclosing Nash’s forecourt on its eastern side. Brighton Pavilion was put on sale in 1846, and the proceeds of the sale (£53,000) were used to fund the renovation. The work was completed in 1847, and the overall cost of the new wing was £95,500.

Whereas when Nash had worked on the Palace, each tradesman negotiated separately for their work, this time, Thomas Cubitt (1788–1855) was responsible for all subcontractors and specialist trades. The laying out of a new forecourt was put in the hands of the architect Decimus Burton (1800–1881) and the landscape designer William Andrews Newfield (1793–1881). New cast-iron railings were made by Henry Grissell at the Regent’s Canal Ironworks. John Thomas (1813–62) carved the railings’ sculptural piers. (Thomas was ‘superintendent of stone carving’ on the Houses of Parliament.)

Blore had an advisory group including Robert Smirke and Charles Barry (responsible for the British Museum and the Houses of Parliament respectively). Despite these safeguards, it was decided to face the new wing in limestone from Caen in Normandy. The stone had previously only been used internally. As early as 1866 it had begun to decay severely in London’s polluted air. For the last forty years of the nineteenth century, the defects had to be concealed beneath layer upon layer of paint.

The new façade was three storeys, and the central frontispiece had giant Corinthian pilasters and a sculptural cresting. By far the most significant element of Blore’s design was the central balcony on the new main East Front façade which was incorporated at Prince Albert’s suggestion. From here, Queen Victoria saw her troops depart to the Crimean War and welcomed them on their return.

On the initiative of architect and urban planner Decimus Burton, a one-time pupil of John Nash, Marble Arch was relocated to the northeast corner of Hyde Park in 1851. The stone by stone removal was fully completed in three months.

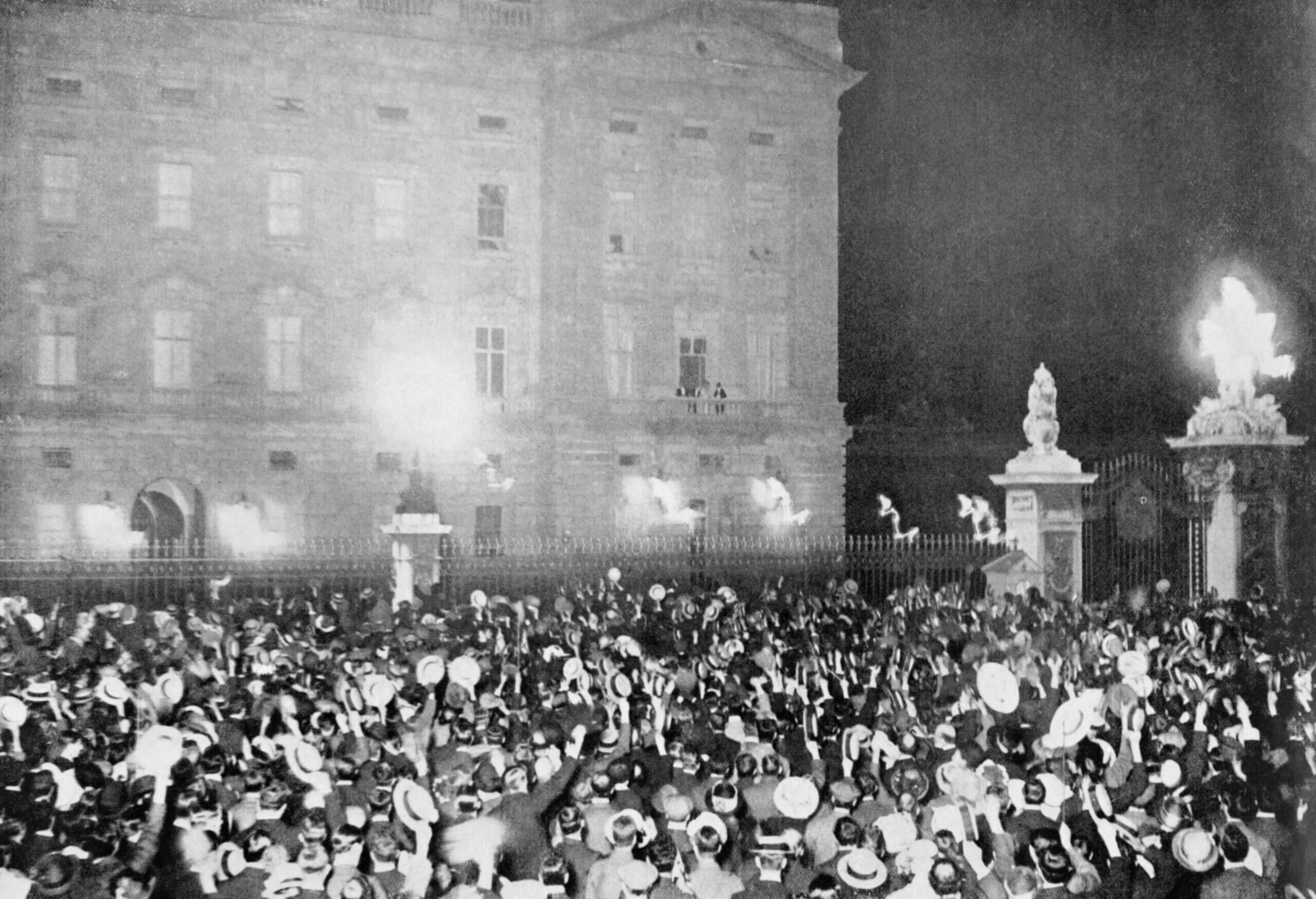

Queen Victoria made the first recorded royal appearance on the balcony in 1851 when she greeted the public during celebrations for the opening of the Great Exhibition – a groundbreaking showcase of international manufacturing, masterminded by Prince Albert.

Also in 1851, Thomas Cubitt submitted designs for a new ballroom on the south side of the Palace. But a year later James Pennethorne (1801–71) was appointed architect. Pennethorne had served his apprenticeship in Nash’s office during the original construction of the Palace. By 1855 he had completed the Ball and Concert Room and the Ball Supper Room, linked by galleries to Nash’s State Apartments at their southern end. The Renaissance-style interiors of the new rooms placed Buckingham Palace in the avant-garde of decoration in England, leading the critic of The Builder to designate the Palace as the ‘Headquarters of Taste’.

After Albert’s death in 1861, the Palace entered a state of decline and for some years looked increasingly derelict and in need of repair.

In 1883 electricity was installed in the ballroom, the largest room in the palace. Over the following four years, electricity was installed throughout the palace, which now uses more than 40,000 lightbulbs.

Nash’s garden front (west side) remains mostly unchanged.

1901–1911

As noted earlier, after Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria spent little time at Buckingham Palace. She declared that nothing for which he had been responsible should be touched. Over those forty years before she died, filthy London air meant not only was the exterior blackened (see above) but the rooms and treasures were covered in coal dust and smoke too.

King Edward VII (reigned 1901–1910) redecorated the interior of the Palace in the new white and gold decorative scheme that can today be seen in a number of the State Rooms, including the Ballroom.

In case it seemed that the new king was erasing his parents’ considerable contributions to the appearance of the Palace – a view later expressed by Queen Mary (George V’s wife) – Edward did extend his patronage to the Queen Victoria Memorial. The Memorial was designed in 1901 unveiled in 1911 and completed in 1924. The sculptor, Thomas Brock (1847–1922) had been an assistant to J.H. Foley on the sculpture of the Albert Memorial. The Mall – a ceremonial approach route to the palace from Admiralty Arch – was designed by Sir Aston Webb and completed in 1911 as part of the grand memorial to Queen Victoria.

Some found the gleaming white marble of the Queen Victoria Memorial sculptures a shocking contrast to the blackened, flaking Palace façade.

In 1911, the gates, railings and forecourt were rearranged. Around the forecourt of the Palace, the railings are capped with nearly a thousand golden fleur-de-lys. There are in-and-out gates on the sides and the centre gates are never opened. All the gates rest on piers carved with dolphins, cherubs, lions and unicorns. They have magnificent bronze coats of arms with pendants of small golden medallions of St George on his horse killing his dragon, six of them in all. On the centre gates are groups of cherubs circling round the lock.

1913–today

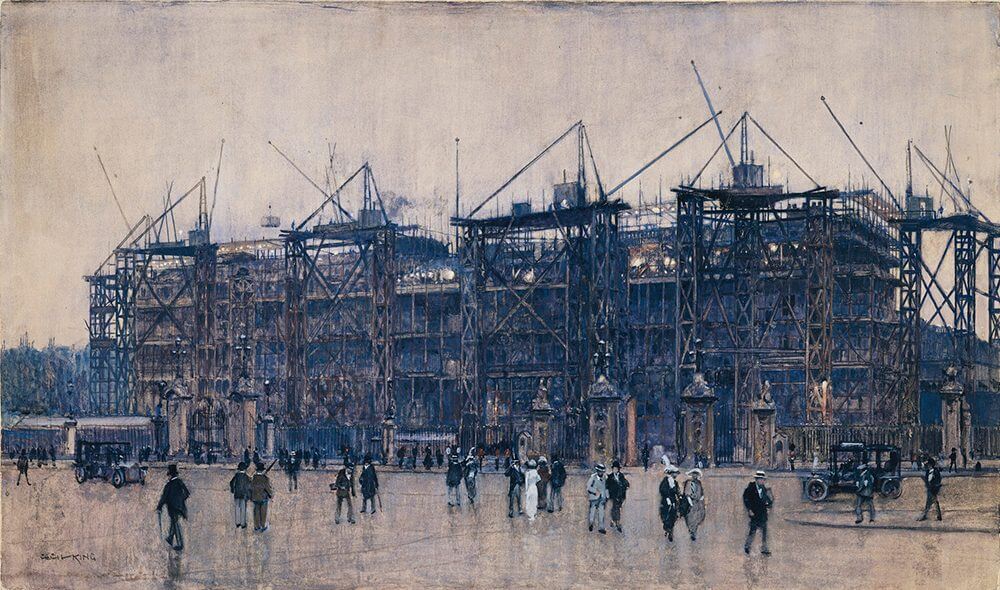

The last major building work took place during the reign of King George V (reigned 1910–1936). In 1913, Sir Aston Webb redesigned Blore’s 1850 East Front to resemble in part Giacomo Leoni’s Lyme Park in Cheshire. This new, refaced principal façade (of harder-wearing Portland stone) was designed to be the backdrop to the Victoria Memorial outside the main gates.

While the incidental objects of Blore’s East Front design were lost, the new Webb’s façade was soon regarded as more stately – not least because it reinstated Nash’s concept of temple fronts at each end with a dominant central pediment.

In 1938, the north-west pavilion, designed by Nash as a conservatory, was converted into a swimming pool.

Unexpected alterations happened in April 1940 and repeatedly in September. Bombs destroyed the south-western conservatory (Queen Victoria’s Private Chapel) and the columned screen at the north end of the East Front, flanking the Sovereign’s Entrance, together with more than 100 metres of the forecourt railings. John Mowlem & Co. was responsible for the careful restoration of the palace when the war was over.

In 1962, on the initiative of The Duke of Edinburgh, The Queen’s Gallery was created from the bombed-out ruins of the former Private Chapel. The Queen’s Gallery was completely refurbished and expanded in 2002 to mark Her Majesty’s Golden Jubilee.

In 1970, the palace was designated a Grade I listed building.

Following the Windsor Castle fire, Buckingham Palace State Rooms have been open to the public each summer since 1993. It was initially suggested it would be for one year to gain funds for repairs at the Castle, but it has remained a well-loved annual London event. I have been fortunate enough to visit many times, so here is my report from 2019. There are plans to be open to visitors in winter 2020.

The palace has steadily been falling into disrepair over the years. (A friend who has worked on security duties at the Palace told me that beyond the spectacular State Rooms many areas are looking very rundown. He spotted mice and rats!) In March 2017 a 10-year schedule of maintenance work was approved by Parliament. This includes new plumbing, wiring, boilers, radiators and solar panel installation on the roof. The costs for this have been estimated at £369 million, to be funded by a temporary increase in the Sovereign Grant paid from the income of the Crown Estate. The maintenance work is intended to extend the working life of the palace by at least 50 years.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!