Before 1829, London’s idea of law enforcement was a chaotic mix of parish constables, night watchmen (nicknamed “Charlies”), and private thief-takers who would catch criminals for reward money. Crime was rampant, and the streets were dangerous after dark. Enter Sir Robert Peel, the Home Secretary who would revolutionize law enforcement and give London’s police officers their enduring nickname – “Bobbies.”

The story begins with a London gripped by fear. The city’s population had exploded during the Industrial Revolution, and the old system of law enforcement simply couldn’t cope. Gangs roamed the streets, pickpockets worked in organized teams, and even respectable neighborhoods weren’t safe after sunset. Something had to change, but many Londoners were deeply suspicious of the idea of a professional police force, seeing it as a step toward military control of the streets.

Peel’s genius was in how he designed his new police force. His officers would wear blue uniforms (not military red), carry no firearms, and be trained to use minimum force. They would be civilians in uniform, not soldiers patrolling the streets. Each officer would be given a number and be personally accountable for his actions. Most importantly, they would prevent crime through their presence rather than simply responding to crimes after they occurred.

The first Metropolitan Police officers took to London’s streets on September 29, 1829. Based at 4 Whitehall Place (with a rear entrance in Scotland Yard – giving the force its famous headquarters name), the initial force consisted of 1,000 men overseen by two commissioners, Charles Rowan and Richard Mayne.

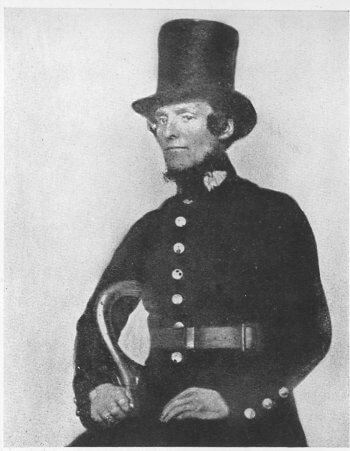

These first officers had a tough time of it. Their uniform consisted of a tall hat (designed to protect against head blows), a heavy blue wool jacket, and white trousers. They carried a wooden truncheon, a pair of handcuffs, and a wooden rattle to raise the alarm (later replaced by whistles). Working in pairs, they walked set beats around the clock, required to cover 20-25 miles per day.

The public reaction was initially hostile. The first recorded death of an officer, PC Joseph Grantham, came just three months into the force’s existence when he was pushed into a canal by an angry crowd. Newspapers criticized the force, publicizing every mistake and misconduct. But gradually, the “Peelers” (as they were also known) began to win public trust.

Some fascinating details from those early days survive. Officers were required to memorize “Peel’s Principles” – nine fundamental rules of policing that emphasized prevention over force and public cooperation over confrontation. They weren’t allowed to vote in elections to maintain political neutrality. And they had to obtain permission from their supervisors to marry!

The force introduced many innovations we now take for granted. They created the first criminal records system, pioneered the use of telegraph communications between stations, and developed the first detective branch (though initially, detectives had to wear uniform while on duty, somewhat defeating their purpose).

Among the more curious regulations was the rule that officers must be at least 5’7″ tall (to be visible above crowds) and be able to read and write (a requirement that excluded many working-class men at the time). They were also forbidden from entering pubs except in the line of duty – a rule that proved particularly unpopular with the officers themselves.

The success of the Metropolitan Police led to similar forces being established across Britain and eventually worldwide. The basic principles Peel established – prevention over cure, minimum force, and policing by consent – became the foundation of modern law enforcement.

Today’s London police officers might have radios instead of rattles and stab vests instead of tall hats, but they’re still following in the footsteps of those first Bobbies. You can visit the small police museum at Scotland Yard, see one of the few surviving police rattles at the Museum of London, or spot the occasional police box (now mostly famous as Doctor Who’s TARDIS) still standing on London’s streets.

Perhaps the most remarkable testament to Peel’s vision is how many of his principles remain relevant today. The idea that the police are the public and the public are the police, that the police should seek public cooperation rather than fear, and that they should use minimum force – these concepts continue to shape modern policing around the world.

So next time you see a London police officer on patrol, remember you’re looking at the heir to a revolution in law enforcement that began on London’s streets nearly two centuries ago. The “Bobbies” didn’t just make London’s streets safer – they created a model of policing that would change the world.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!