Picture this: It’s 1348, and London is about to host the most unwelcome visitor in its history. No, not your in-laws or that friend who always overstays their welcome – we’re talking about the Black Death, the granddaddy of all pandemics. Buckle up, folks, because things are about to get medieval!

Our story begins in the bustling port of Melcombe Regis in Dorset, where a ship from Gascony docks in June 1348. Little do the eager traders know, but along with their goods, they’re importing a microscopic menace that’s about to change England forever. The Black Death has arrived, and it’s heading for London with the speed and inevitability of a modern-day Tube commuter.

By autumn, the plague reaches the capital, and let’s just say it doesn’t exactly receive a warm welcome. At first, Londoners try to go about their business as usual. After all, they’ve dealt with diseases before. But this isn’t your average seasonal sniffle – this is the Black Death, and it’s about to turn London’s world upside down.

The symptoms are as gruesome as they are terrifying. Victims develop painful swellings called buboes (hence the term “bubonic plague”), high fevers, and in some cases, their skin turns black (giving the disease its cheery nickname). It’s like the worst hangover you’ve ever had, multiplied by a thousand, with a side of existential dread.

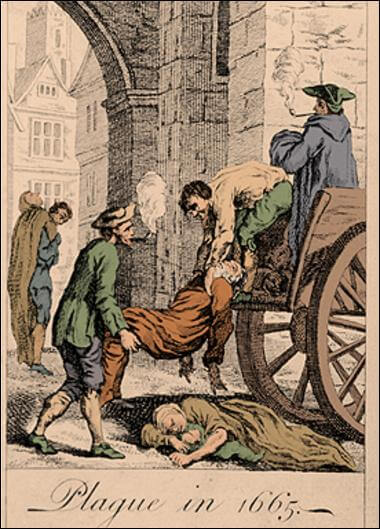

As the death toll mounts, panic sets in. The streets of London, usually a cacophony of shouts, laughter, and the occasional drunken brawl, fall eerily quiet. The only sounds are the mournful cries of “Bring out your dead!” as corpse-collectors make their grim rounds. It’s like a medieval version of garbage day, but infinitely more depressing.

Speaking of depressing, let’s talk numbers. By the time the Black Death finally packs its bags and leaves in 1350, it’s estimated that half of London’s population has been wiped out. That’s right – imagine looking around your office or your local pub and half the people just… gone. It’s a demographic disaster that makes modern-day London rush hour look positively crowded.

But what caused this catastrophic calamity? Well, for centuries, people blamed everything from bad air to divine punishment. Some even pointed fingers at cats, leading to a feline genocide that, ironically, probably made things worse by allowing the rat population to explode. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that we figured out the real culprit: a bacterium called Yersinia pestis, spread by fleas living on rats. Yes, London was brought to its knees by the medieval equivalent of a bad Airbnb review: “Great location, but too many disease-carrying rodents. One star.”

Now, you might be thinking, “Surely they had doctors to help?” Well, yes and no. Medieval medicine was… let’s say, creative. Treatments ranged from the useless (rubbing onions on the buboes) to the downright dangerous (bleeding patients to “balance their humors”). Some physicians wore beak-like masks stuffed with herbs, looking like deranged plague-fighting ducks. Spoiler alert: it didn’t help.

As the plague raged on, social norms went out the window faster than a medieval chamber pot’s contents. Many wealthy Londoners fled to the countryside, while those who stayed often abandoned sick family members. Others took a more “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die” approach, indulging in wild behavior. It was like Freshers’ Week, but with more death and fewer regrettable tattoos.

The economy took a massive hit too. With so many workers dead, labor became scarce, and suddenly peasants could demand higher wages. It’s the medieval version of the Great Resignation, but with more boils and less Zoom fatigue.

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom (okay, it was mostly doom and gloom, but bear with me). The Black Death, terrible as it was, led to some significant changes. The shortage of laborers eventually contributed to the decline of the feudal system. The English language got a boost as the plague disproportionately affected the French-speaking nobility. And the medical profession, realizing that bleeding people and rubbing them with onions wasn’t cutting it, began to embrace more scientific approaches.

In London itself, the aftermath of the Black Death saw some positive developments. New sanitation measures were introduced (turns out, not living in your own filth is good for you – who knew?). The city began to expand beyond its walls as people sought less crowded living conditions. And with fewer mouths to feed, those who survived often found themselves better off economically.

As London slowly recovered, it demonstrated the resilience that would become its hallmark. The city had stared death in the face and, while battered and bruised, survived to tell the tale. In the following centuries, London would face fire, war, and even more plagues, but none would match the impact of the Black Death.

So, the next time you’re stuck in London traffic or squeezing onto a packed Tube train, spare a thought for those medieval Londoners. They faced the worst pandemic in human history with nothing but dodgy medicine, questionable hygiene, and a stiff upper lip. The Black Death may have been London’s deadliest uninvited guest, but it didn’t manage to kill the city’s spirit. Now that’s something worth raising a pint to – just make sure to use hand sanitizer first!

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!

Jonathan – I have a question, not a comment: The painting of the plague scene at the top of this article – who was the painter? Title of the painting? Thank you.

This is the painting! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Triumph_of_Death