Traditionally a song or a poem meant to entertain children; many nursery rhymes are so old that their original meanings have long been forgotten by modern audiences. Much like the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen, there are darker themes and meanings behind what we treat as harmless kids’ fare. With its long history full of dark and troubling times, London has been the origin place of several nursery rhymes. The symbolism help within these simple rhymes secretly portrays some of the worst moments in its past.

London Bridge is Falling Down

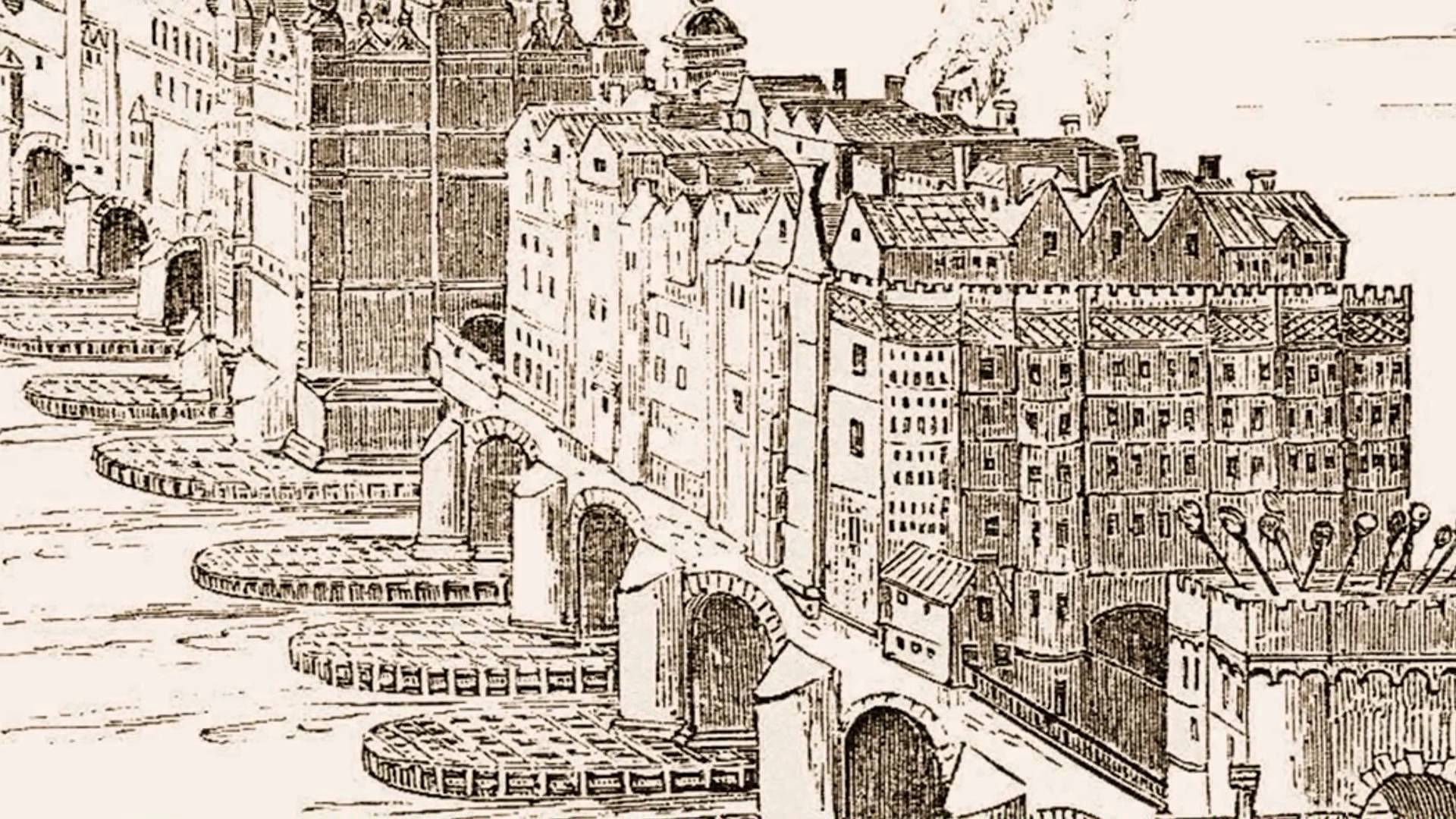

One of the most well-known nursery rhymes ties its history directly to what was, for centuries, London’s only bridge over the River Thames. The bridge, in one form or another, had existed since the Roman occupation, and one theory behind the nursery rhyme is that one of the older, wooden bridges was destroyed by Olaf II of Norway during a Viking raid. This comes from an Icelandic court poet in the 11th Century who wrote a verse very similar to the nursery rhyme. A more popular theory assumes that the poem refers to the normal wear and tear that befell Old London Bridge, which had existed since 1176 and wasn’t replaced until 1832. It was subject to numerous construction and repair over its 600-year-plus history, including the removal of supports, the building of homes and shops, and the eventual tearing down of those same structures. Another theory is that the song describes the human sacrifice of children to keep the bridge up, but let’s admit that’s just a bit daft.

The Muffin Man

Might seem like a harmless song about a man selling muffins on Drury Lane, but at least one theory purports a much darker subtext. Americans know this type of muffin as English Muffins, a thinly-sliced piece of yeast-laden bread eaten at breakfast. These were a popular food item with the working classes but became a staple food after their popularity extended to all classes in British society. The more popular origin theory is that the song simply and cheerily refers to the man who would go about selling these baked goods. Another theory, however, is quite a lot darker and more than just a little outrageous. It posts that a 16th Century serial killer named Frederic Thomas Lynwood who would lure children into his bakery with a muffin tied to a string, earning him the nicknames “The Muffin Man” and “The Drury Lane Dicer.” Of course, none of this can be substantiated, so the former theory is likely the most accurate.

Pop Goes the Weasel

A fun little song, Pop Goes the Weasel has a more depressing origin related to excess, poverty, and ruin. There are many different versions, but the earliest ones published in the 1850s goes “Up and down the City Road/In and out the Eagle/That’s the way the money goes/Pop goes the Weasel!” These more adult lines describe the effects of losing one’s money from excess drinking in the pubs along the City Road (also known as the A501), of which the Eagle is still there on Shepherdess Walk. Another original verse describes getting nicked for poaching. The American version cleans up the lyrics quite a bit into something more fun and jovial, which is the version that most people know today.

Tweedledee & Tweedledum

The characters made famous by Lewis Carroll don’t actually originate with Alice in Wonderland. In fact, they come from a nursery rhyme that predates Alice by nearly a century. Poet John Byrom used the names to satirise a rivalry between the great composers Giovanni Bononcini and George Frederic Handel when the pair lived in London. As the rhyme goes, “Some say, compar’d to Bononcini/That Mynheer Handel’s, but a Ninny/Others aver, that he to Handel/Is scarcely fit to hold a Candle/Strange all this Difference should be/’Twixt Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee!” The names caught on with the public and, over time, came to symbolise two similar people who were fighting with each other. The more well-known version of the nursery rhyme the depicts the two fighting was published in 1805 and, sixty-six years later, the brothers enact their nursery battle for Alice when she finds them in Wonderland.

Oranges and Lemons

Most people might know this particular nursery rhyme from George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984. While today the song refers to London’s various church bells, from St. Martin-in-the-Fields to St. Clement’s, several theories exist behind its origin that mirror those of London Bridge. The last couplet goes, “Here comes a candle to light you to bed/And here comes a chopper to chop off your head!” has been inferred by some to refer to child sacrifice or child murder. Another theory is that these lines refer to public executions, accompanied by the ringing of bells. The execution theory seems far more likely, considering how condemned persons would be led through the streets as the church bells rung. Previous lines in the song also make reference to money-borrowing and suggest how borrowers who could not pay back what they owed, though debtors were not typically executed for this crime. It certainly seems likely that the final, more gruesome, lines were added later than the original ones for some unknown reason.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!

I must differ with your interpretation of “Pop Goes the Weasel.” It refers to spinning. After you have spun your thread, you need to get the thread off your spinning wheel’s bobbin and wind it into measured skeins of yarn or thread. So you tie your thread to a counter that looks like a stand with arms coming off an axle. The circumference of these arms is 2 yards – and with yarn on it, it looks rather like a tree. In the center is a device called the weasel made of wood and screws. You set the weasel for the length you want – 40 turns for 1 skein, 80 for 2, etc; when you’ve spun the reel that many times, the weasel pops. When the weasel pops, it’s time to stop winding and make a skein out of the thread that is on the reel – one that you know will have the right amount of thread in it. Spinning was a home industry, and the song was devised to keep children turning steadily while they waited for the weasel to pop.

The spinning version of “Pop goes the weasel” is the one we were taught as well. Here on Cape Cod, MA there’s a marvelous little home called the Hoxie House (One of the oldest house on the Cape circa 1675) which gives historical tours…the spinning explanation is the one they give as they show you how it was done with the spinning wheel and yarn.

My mother, a cockney, whose grandfather was a tailor, told us that the line “Pop goes the weasel” means that the weasel

a specific iron used by tailors. and of course “Pop” means to pawn. So along with what you have written the tailor, having drank and spent to excess had to pawn his iron which was essential to his work.