To celebrate 50 years since NASA’s Apollo 11 mission landed the first humans on the Moon, the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich is staging the UK’s biggest exhibition dedicated to Earth’s nearest celestial neighbour. The Moon is open from 19 July 2019 and charts the cultural and scientific story of our relationship with the moon through over 180 objects, including artefacts from NASA’s Apollo 11 mission. The exhibition explores how humans have used, understood and observed the moon from Earth.

Section 1

The exhibition is in four sections and poses lots of questions. It starts with ‘What will the moon mean to us in the future?’ and ‘What does the moon mean to you?’ The exhibition doesn’t intend to answer all your questions but it will certainly get you thinking.

A small engraving by William Blake in 1820 entitled I want! I want! embraces the ethos of the exhibition. The desire to want to know more about the moon. To know how to get there and how to hold onto it.

In the exhibition’s opening section, it looks at how we have been observing the moon and understanding the phases for thousands of years. It looks at how we have relied on the moon for practical, emotional and artistic purposes.

There is a large wall of moon phases, with the dates from July to December, to cover the dates throughout the exhibition, so you can see the moon phase on the day of your visit.

The oldest object on display is a Mesopotamian Tablet from 172 BCE on loan from the British Museum that shows how lunar eclipses were considered to be bad omens.

This section explores how the moon has permeated in our belief systems.

The exhibition moves on to practical uses such as health and medicine, and tides and navigation.

Examples of historic medical texts, such as a 1708 pamphlet by the English Doctor Richard Mead show how the position of the moon was once believed to influence our physical and mental health. If you saw a 16th-century doctor he would have asked when your symptoms started and then checked a lunar calendar.

Detailed Islamic and Chinese calendars highlight the continuing importance of using the noon to set the date for key festivals such as Chinese New Year and Ramadan.

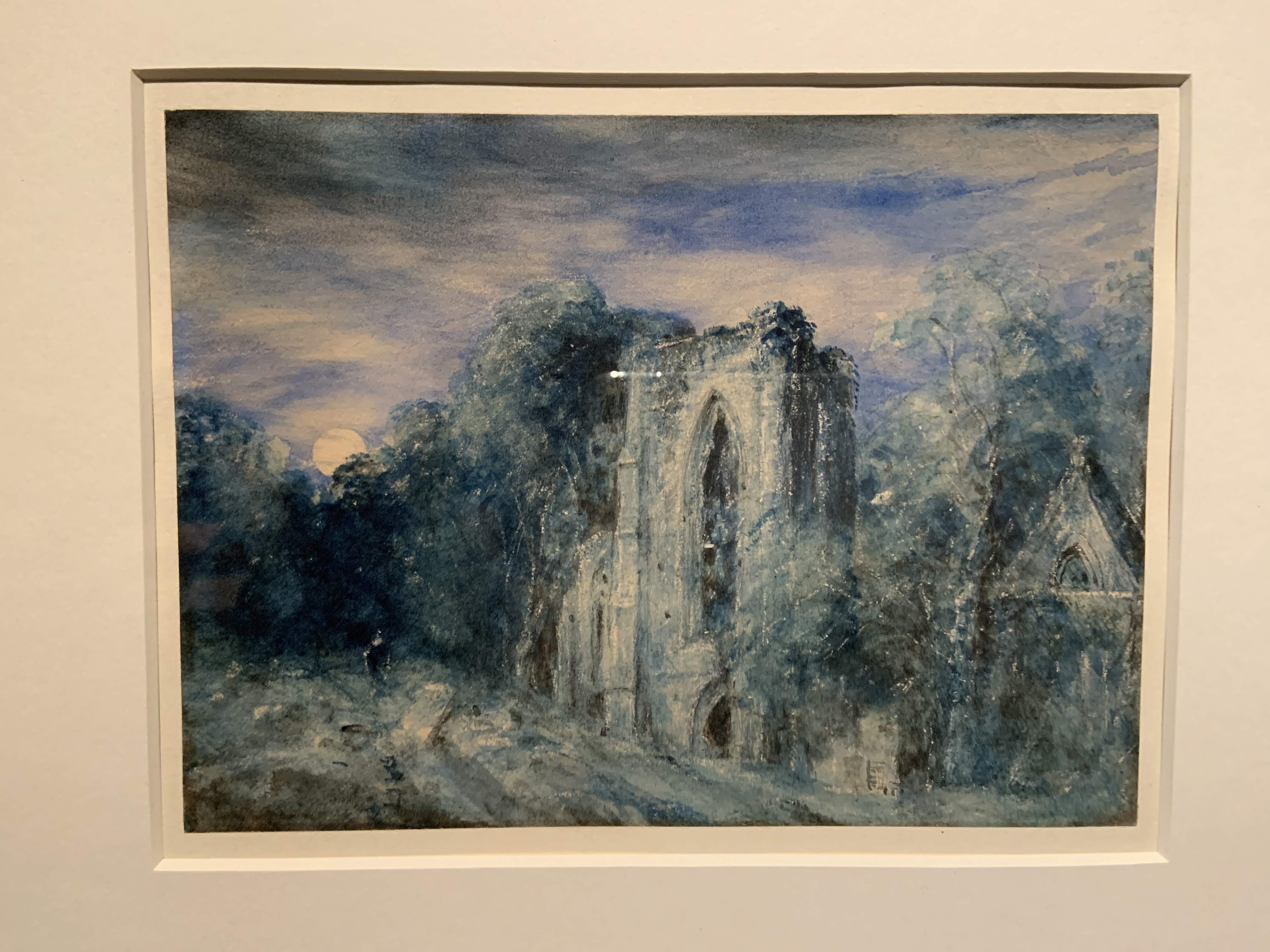

This area is complemented by moonlit scenes by J.M.W. Turner and John Constable displayed alongside contemporary pieces by Katie Paterson, El Anatsui, Chris Ofili and Leonid Tishkov.

Constable’s painting of Netley Abbey was made almost 20 years after he went there on his honeymoon. He produced this work after his wife died and you can feel the sadness and melancholy in this artwork.

Section 2

The second section has 17th-century astronomer Galileo Galilei’s telescope and moon portraits (detailed pastel drawings of the moon) by 18th century Royal Academician John Russell. By day, Russell produced portraits of fashionable society and rubbed shoulders with influential figures of science. By night, he spent 20 years observing and making images of the moon.

The first photographs of the moon were taken in the 1840s, not long after the invention of photography. It looks at early photography and includes ‘Atlas photographique de la lune’ from 1894-1910. It took Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux 14 years to complete their large moon atlas. Photographs required clear conditions and the astronomers could only take them on about 50-60 nights each year.

James Nasmyth made a fortune as an industrial engineer. At 48, he retired and devoted his life to astronomy. He designed his telescope – one of the biggest at the time – to have a turntable with a built-in seat. This meant he could direct it anywhere in the sky without getting up.

From drawings he made at the telescope, he produced first paintings and then plaster models to help describe the lunar surface. Photographs of these were then published in his book, in which he proposed a theory of lunar formation. In line with many 19th-century ideas about how the moon’s features were formed, he suggested lunar craters had a volcanic origin.

Displays also include the earliest-known drawing of the lunar surface made from telescopic observations by British astronomer Thomas Harriot in 1609.

And there is Hugh Percy Wilkins’ Moon map. It’s 100 inch diameter and was published in 1951. Wilkins was a civil servant by day and observed the moon at night. This was the most detailed map of the moon when published.

This might be a good point to mention what it is like inside the exhibition space. It’s dark throughout with lighting only on the exhibits. There is gentle piano music in the background although I’m not sure of its relevance. There is some seating towards the end of the exhibition route. There are simplified captions with blue borders as well as the detailed versions.

Section 3

This section is about fictional as well as actual journeys to the moon. There are books by H.G. Wells and Jules Verne and a poster for Kubrick’s Space Odyssey: 2001. (Do read about the Stanley Kubrick exhibition on at the Design Museum.) The film was released in 1968, a year before the Apollo 11 landing.

There is a timeline noting the first animal in space in 1957, the first man in space in 1961, the first space walk in 1965 and the first man on the moon in 1969. The Space Race –driven by the Cold War rivalry between the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union – is explained in simple terms and there are listening posts to hear archive sound clips. So many Soviet ‘firsts’ were ultimately overshadowed by Neil Armstrong’s century-defining ‘one small step’ in July 1969.

The Saturn V rocket was used to launch the Apollo spacecrafts. At 111 metres high, it remains the tallest, heaviest and most powerful rocket ever built.

There are space-themed books, comics, wallpaper, toys and even a patchwork denim jacket. There’s a video by artist Christian Stangl which uses 32,000 still images from Apollo missions to create a film from take-off to landing and back again.

While Neil Armstrong is the figurehead, there were 400,000 people behind the Apollo space project. It cost an incredible $25 billion.

Loaned from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C., you can see the “Snoopy cap” Communications Carrier worn by astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin during Apollo 11. It transmitted messages between the crew and ground control.

There’s also the flight plan for the Apollo 11 landing and the Hasselblad camera equipment that captured some of the most recognisable and iconic images of the 20th century.

The exhibition does address the ‘fake landing’ reports in one cabinet but that’s obviously nonsense.

Section 4

The Apollo space project came to an end in 1972 with Apollo 17. Today, there is renewed drive to return to the moon, reflected in future projects from China, Europe, India, Israel, Japan, Russia and the United States. No longer the domain of superpowers, international space agencies, private companies and entrepreneurs are all part of this 21st-century race for the moon.

This section poses the question: ‘Who owns the moon?’

This closing chapter of the exhibition looks at the contemporary motivations for moon travel, leaving visitors to contemplate whether the moon will become a theatre for exploitation and competition or remain a peaceful place for all humankind.

Through the Apollo missions, around 380kg of moon rock have been directly collected from the surface. You can see lunar samples collected from NASA’s Apollo missions and the Soviet Union’s Luna programme as well as a rare lunar meteorite from the Natural History Museum’s collection. These specimens are small – some are less than a grain at rice – but still fascinating to see.

On display are other objects that led to the preparation of the Apollo 11 landing and a final section about the idea of living on the moon.

Don’t miss the Outer Space Treaty brought out of the National Archives. This was signed by Moscow, Washington and London – this is the London copy.

At the exit, there are three questions for visitors.

Visitor Information

Dates: 19 July 2019 – 5 January 2020

Address: National Maritime Museum, Park Row, Greenwich, London SE10 9NF

Opening Times: 7 daus a week, 10.00 – 17.00

Admission: Adult £10.00 | Child £6.50 | Concession £6.65

Website: www.rmg.co.uk/moon50

As well as The Moon exhibition, the National Maritime Museum is hosting a series of events. There are film screenings in London’s only Planetarium, family festival days celebrating the cultural significance of the moon and Royal Observatory Lates that provide a behind the scenes insight into studying and photographing the moon.

And The Queen’s House presents newly commissioned photographic works titled Mortal Moon. They are a creative response to the Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I and have been inspired by the fragile vessels travelling the oceans at the mercy of heavenly and earthly forces.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!