Few things are more quintessentially British—and more deeply woven into London’s cultural fabric—than fish and chips. This humble meal of battered fish and fried potatoes has transcended its working-class origins to become a national treasure, a comfort food icon, and perhaps the most recognized symbol of British cuisine worldwide. From Victorian street corners to modern chippies, fish and chips tells the story of London itself: a city built by waves of immigration, sustained by working people, and united by shared traditions.

The Origins: Two Immigrants, One Perfect Marriage

The story of fish and chips is really two stories that merged into culinary perfection in Victorian London. Fried fish arrived first, brought to Britain’s shores by Sephardic Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution in Portugal and Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries. They brought with them the practice of coating fish in flour and frying it—a method that preserved the fish for eating on the Sabbath when cooking was forbidden. By the mid-19th century, fried fish had become popular street food in London’s East End, sold from wooden stalls and eaten cold.

Chips—or “chipped potatoes” as they were originally known—have a murkier origin story. While the French and Belgians both claim to have invented fried potatoes, it was likely Northern England where chips as we know them first appeared in the 1860s. Working-class families in industrial cities began frying thick-cut potato slices as a cheap, filling meal.

The genius moment came when someone—history isn’t entirely certain who—decided to marry these two immigrant traditions. The most commonly credited innovator is Joseph Malin, a Jewish immigrant who opened the first combined fish and chip shop in London’s East End around 1860. His shop on Cleveland Street in Whitechapel (now Cleveland Way, just off the Mile End Road) served battered fried fish alongside chips, wrapped in newspaper to keep warm and eaten straight from the paper.

Another contender is John Lees, who opened a similar establishment in Lancashire around the same time. The debate continues, but London certainly claims the crown for making fish and chips a cultural institution.

The Rise of the Chippy

Within decades, fish and chip shops—affectionately known as “chippies”—spread across London like wildfire. By the 1910s, there were over 25,000 fish and chip shops across Britain, with London boasting thousands. These weren’t fancy establishments; they were utilitarian, often cramped shops with simple tile walls, steamy windows, and the intoxicating smell of frying fish and vinegar wafting into the street.

The appeal was simple: fish and chips were cheap, hot, filling, and portable. For working-class Londoners enduring long factory shifts, backbreaking dock work, or cramped tenement living, a tuppence worth of fish and chips represented an affordable luxury. You didn’t need plates, cutlery, or even a table—just your hands and an appetite.

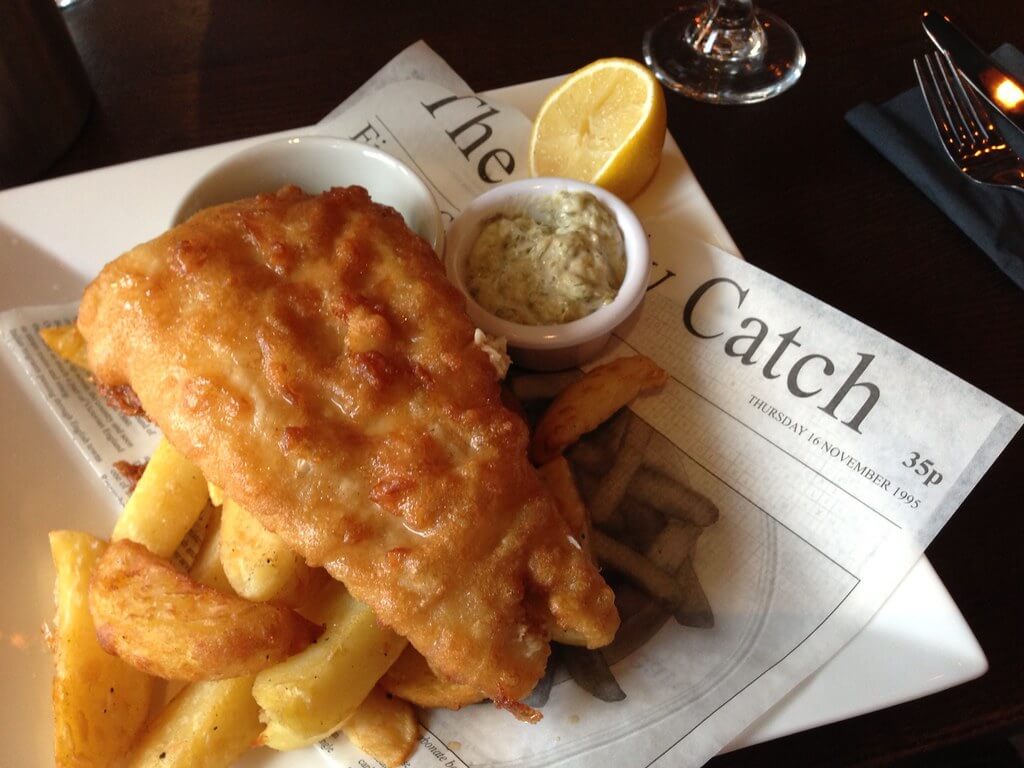

The tradition of wrapping fish and chips in newspaper became iconic in itself. Old newspapers (often several days out of date) served as both insulation and plate, adding a distinctly London touch to the meal. Customers would unwrap their warm parcel, sprinkle it liberally with salt and malt vinegar, and dig in. The practice continued until the 1980s when health regulations finally banned newspaper wrapping due to ink concerns, but many chippies still use printed paper styled to look like vintage newsprint, keeping the tradition alive aesthetically if not literally.

Fish and Chips Goes to War

Fish and chips cemented its status as a British icon during both World Wars. Recognizing the dish’s importance to national morale, the government exempted fish and chips from rationing—one of the few foods to receive such treatment. Winston Churchill famously called the combination “the good companions,” acknowledging that this simple meal sustained both bodies and spirits during Britain’s darkest hours.

During the Blitz, when London endured nightly bombing raids, fish and chip shops became symbols of resilience and normalcy. Despite the danger, many chippies stayed open, providing hot meals to exhausted Londoners sheltering in Tube stations or emerging from rubble-filled streets. The sight of a chip shop’s lights and the smell of frying fish represented continuity, comfort, and the determination to carry on.

The Golden Age and Evolution

The post-war years through the 1960s represented the golden age of the traditional chippy. Nearly every London neighborhood had its beloved local shop, often family-run and passed down through generations. These establishments became community hubs where neighbors gathered, exchanged gossip, and bonded over their shared love of a perfectly crispy batter.

The classic experience involved queuing (naturally—this is Britain), often in the rain, watching the fryer work their magic through steamed-up windows. The ritual was specific: you’d order your fish (cod and haddock being the traditional choices, though plaice and skate also featured), specify your portion of chips, then watch as the server wrapped it all in paper with practiced efficiency. Salt? Vinegar? Always. Mushy peas? Optional but traditional. Curry sauce? A Northern addition that gradually made its way south.

London’s Chippy Culture

While fish and chips are beloved throughout Britain, London’s relationship with the dish has unique characteristics. The capital’s diverse immigrant communities have added their own twists—some chippies in East London serve their fish with a side of pickled cucumber, a nod to the Jewish origins. In Bethnal Green and Stepney, you’ll still find traditional establishments that have been frying fish for over a century, their walls decorated with fading photographs of Victorian London.

London also pioneered the “sit-down chippy,” transforming what was purely takeaway food into a restaurant experience. Establishments like Poppies in Spitalfields (opened in 1952, revived in 2008) created 1950s-themed dining rooms where customers could enjoy their fish and chips at proper tables with tea in china cups, adding a touch of nostalgia and occasion to the meal.

The London cabbie’s relationship with fish and chips deserves special mention. For generations, black cab drivers have had their favorite chippies along their routes, often engaging in spirited debates about which establishment serves the best. Many historic chip shops have stayed in business largely thanks to loyal cabbie customers who’ve been coming for decades.

Modern Revival and Gourmet Evolution

The late 20th century saw fish and chips face competition from burgers, pizza, and other fast foods. Many traditional chippies closed, and the dish risked becoming a nostalgic memory rather than a living tradition. But the 21st century brought unexpected revival.

A new generation of chefs and food entrepreneurs recognized fish and chips’ iconic status and set about reinventing it for modern tastes while respecting tradition. High-end establishments like The Golden Hind in Marylebone (opened 1914) and Sutton and Sons in Stoke Newington began emphasizing sustainable fishing, premium ingredients, and perfect technique. Celebrity chefs got involved, with establishments like Rick Stein opening fish and chip restaurants.

London’s fish and chips scene now ranges from traditional no-frills takeaways to gastropub versions with craft beer, and even Michelin-adjacent interpretations. Yet the core remains unchanged: perfectly fresh fish, encased in light, crispy batter, served with golden chips.

Why It Matters

Fish and chips represents London in miniature: a working-class staple elevated to cultural icon, a fusion of immigrant traditions, and proof that the simplest things often matter most. It’s democratic food—equally enjoyed by lords and laborers, tourists and lifelong Londoners. You can spend £5 at a corner chippy or £25 at a restaurant, but you’re eating essentially the same dish that sustained Victorian dockers and Blitz survivors.

The smell of a good chip shop—that particular combination of frying oil, malt vinegar, and the sea—is as evocative of London as fog on the Thames or the chimes of Big Ben. It connects us to the city’s past while remaining vibrantly part of its present.

Today, whether you’re grabbing takeaway after the pub, introducing visitors to British cuisine, or seeking comfort food after a long day, fish and chips delivers. It’s a taste of London history, wrapped in paper (even if it’s not newspaper anymore), best enjoyed with your fingers, and utterly, perfectly British.

Long may the chippies fry.

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!