This Tate Britain exhibition explores Caribbean-British art over four generations. There is an open admittance that, like much of the mainstream British art world, Tate was late to recognize many of the artists included. But that is being rectified now with this celebration of this cross-cultural genre of art.

Denzil Forrester Jah Shaka, 1983. Collection Shane Akeroyd, London © Denzil ForresterOver Forty Artists

This is the first time a major national museum has told this story in such depth. It showcases 70 years of culture, experiences, and ideas expressed through art. The exhibition features over 40 artists, including those of Caribbean heritage as well as those inspired by the Caribbean, such as Ronald Moody, Frank Bowling, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, Peter Doig, Hew Locke, Steve McQueen, Grace Wales Bonner, and Alberta Whittle, working across film, photography, painting, sculpture, and fashion.

Most of the artists represented are of Caribbean heritage: they were born in the Caribbean and came to Britain, either as adults or children, or were born of parents who settled in Britain.

Social History

I’ve been really looking forward to seeing this exhibition, especially after I was so critical of Tate’s Hogarth and Europe exhibition. It wasn’t that the chosen artworks were wrong, but the heavy-handed shoehorning of colonial slave information was distracting.

But this exhibition has the right to include that history and tell a story from a different perspective. Britain’s history is profoundly intertwined with the Caribbean’s. Histories that may be familiar to Caribbean-British people are insufficiently known in Britain generally. As a white British, I’ve lived alongside this but not within it. And I’d never presume to think all black people know about this stuff either. We are not born with this knowledge; we learn it. So I entered with an open mind and a keenness to discover more.

I often tell my daughter that everyone’s “normal” is different. While you can spend all day together at school, you go back to a different home with people who have different rules and values. Those influences make us unique even when we haven’t yet realized it ourselves.

The timing of this exhibition is superb as on 30 November 2021, Barbados became the world’s newest republic as the island nation removed the Queen as its head of state. The former British colony, which gained independence in 1966, revived its plan to become a republic last September with the country’s governor-general, Sandra Mason, saying, “the time has come to fully leave our colonial past behind.”

Arrivals

The exhibition begins with artists of the Windrush generation who came to Britain in the 1950s, including Denis Williams, Donald Locke, and Aubrey Williams. Some came to study, later developing careers as artists and writers. The 1948 British Nationality Act invited the ‘Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ to ‘return to the mother country.’

It explores the Caribbean Artists Movement, an informal group of creatives like Paul Dash and Althea McNish, whose tropical modernist textile designs were inspired by the Caribbean landscape.

Ronald Moody moved to Paris in 1938 but was forced to flee in 1940, two days before it fell to Nazi occupation. He returned to Britain in 1941, where he remained until his death in 1984. In the 1950s and 1960s, Moody exhibited regularly in London. The Onlooker (below) is a rare work in wood from this period and reveals his view of the artist’s role in society as an observer. In the late 1960s, Moody became an active member of the Caribbean Artists Movement. In 1970, the movement named their journal, Savacou, after his sculpture of a mythical Carib bird for the University of the West Indies, Jamaica.

The end of the Second World War led to an increase in momentum for Caribbean independence movements seeking self-governance of territories of the British Empire. Beginning in 1962 with Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, ten former British colonies became independent nations over the next two decades. This process of decolonization had a strong cultural dimension as colonialism enforced British cultural values and systems of oppression on Caribbean territories and peoples.

In Guyana, the culture of its indigenous peoples, known locally as Amerindians, had a particularly profound impact. Several Guyanese artists and writers who migrated to Britain created abstract and surrealist artworks drawing on Amerindian spiritual beliefs and visual culture. Using these references was a symbolic means of putting down roots, reconnecting with the natural world, and evoking the culture of their own African ancestors. Some have called this process neo-indigenization.

The two paintings below are by Frank Bowling, who was born in Guyana in 1934. Shortly after moving to New York in 1966, Bowling created a series of paintings consisting of flat areas of saturated color. The works are reminiscent of other American color field paintings of that time. However, unlike other color field artists, many of Bowling’s works include stenciled outlines of continents. The series became known as Bowling’s ‘map paintings.’

Paul Dash was one of the youngest members of the Caribbean Artists Movement. Born in Barbados, he moved to Oxford with his family at the age of eleven before studying at London’s Chelsea College of Art in the 1960s. He settled in London and has spent decades making and teaching art and education here. When he entered art school, abstract painting was the fashion, and it wasn’t until he painted Self-portrait in 1979 and returned to figuration that Dash felt he’d regained his artistic voice.

In Talking Music (1963), seen below, Dash paints himself and his siblings watching a lively debate between their brother, father, and his friend. Together they formed the Carib Six, a family band that toured the UK, in which the artist (far left) played the piano.

Pressure

Charlie Philips arrived in London from Jamaica at the age of twelve. He began taking photographs at the age of fourteen and later worked as a freelance photographer for magazines including Harper’s Bazaar, Life, and Italian Vogue. While living in Notting Hill in the 1960s, he photographed his friends and neighbors. Notting Hill was home to a growing Caribbean community often living in decaying, overcrowded properties owned by exploitative landlords. They were prevented from living in many other areas of London by an informal ‘color bar.’

Phillips has said, “As far as I’m concerned, we haven’t been given a proper platform to show our culture, our side of the story… It’s not Black history; this is British history, whether you like it or not”. I have to agree; this is clearly British history.

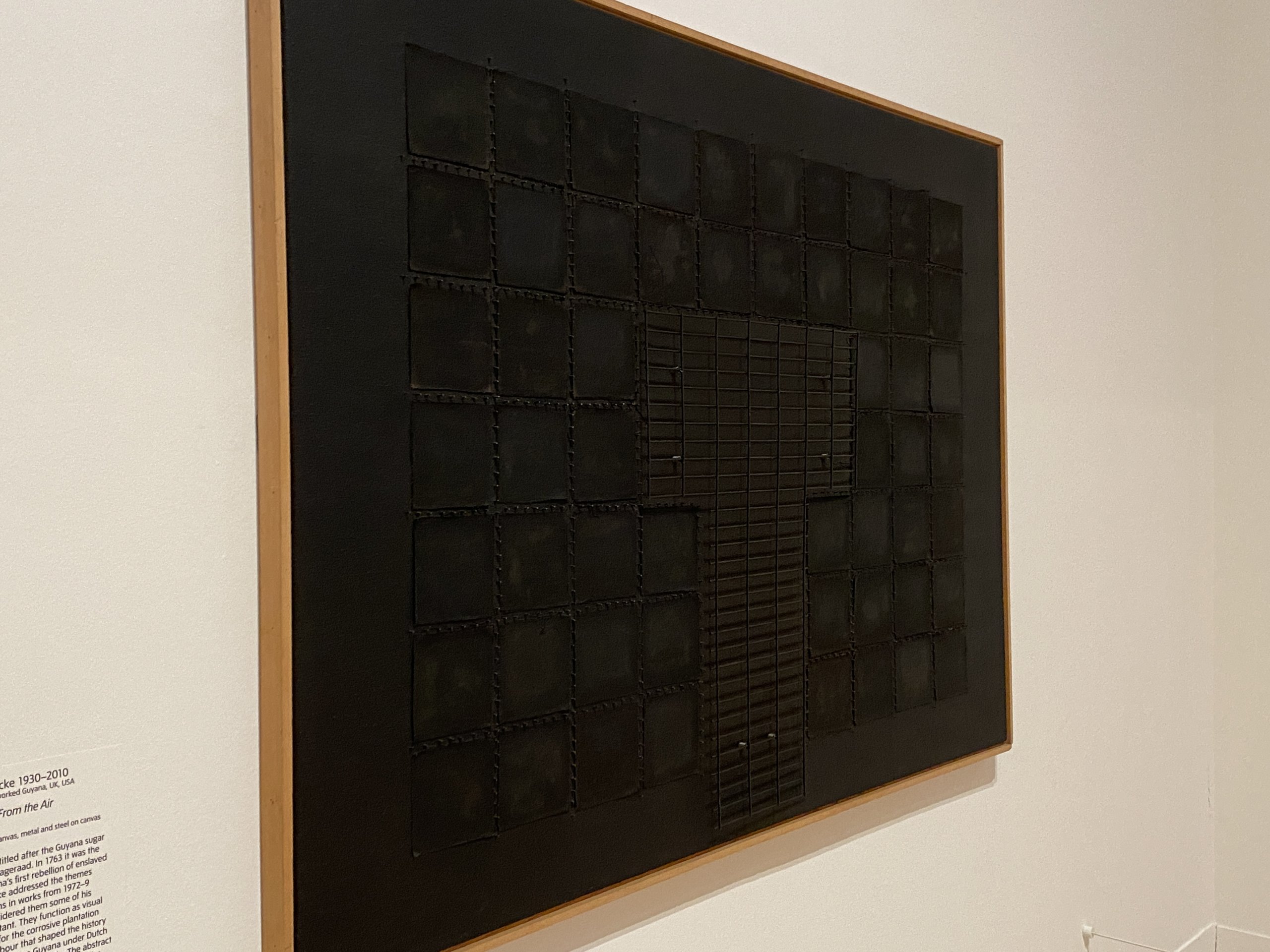

Dageraad From the Air (1978-9) by Donald Locke (1930-2010), who was born in Guyana, is named after the Guyana sugar plantation Dageraad. In 1763 it was the site of Guyana’s first rebellion of enslaved people. Locke addressed the theme of plantations in works from 1972–9, and he considered them some of his most important. The abstract minimalism of this painting reflects the brutal uniformity of colonial rule and slavery, which reduced people and land to expendable commodities.

Locke’s Trophies of Empire (1972-4) consists of an open wooden cabinet filled with ceramic cylindrical forms mounted on a range of holders. Locke described the cylinders as bullets yet embraced their ambiguity. They might depict victims of violence, isolated figures stripped of identity, or phallic forms displayed in a celebratory display of force.

In 1968 Frank Crichlow opened the Mangrove restaurant in London’s Notting Hill. An important meeting place for the Black community, it became the target of regular police raids. On 9 August 1970, the British Black Panthers organized a march of 150 people to the local police station to protest against police harassment of the restaurant and its customers. Protestors were met by 500 police officers, and nine arrests were made: Barbara Beese, Rupert Boyce, Frank Critchlow, Rhodan Gordon, Darcus Howe, Anthony Innis, Althea Lecointe-Jones, Rothwell Kentish, and Godfrey Millett. The group became known as the Mangrove Nine. A high-profile trial was held at the Old Bailey. Howe and Lecointe-Jones defended themselves, and five of the defendants were acquitted of the main charge of ‘incitement to riot.’ The trial saw the first judicial acknowledgment of ‘evidence of racial hatred’ in the Metropolitan Police. These Horace Ové photographs depict Howe and Beese, both leading members of the British Black Panthers.

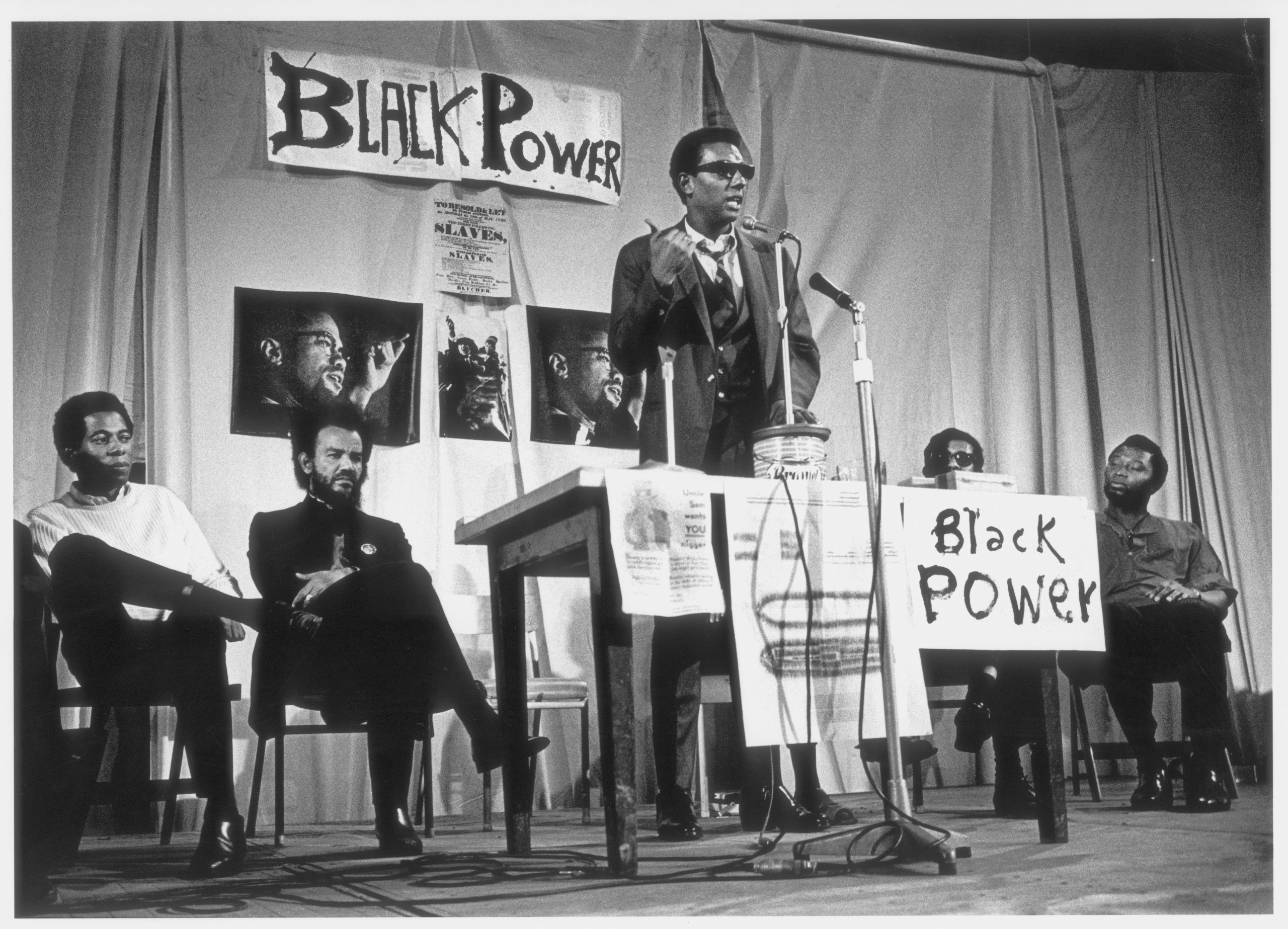

The Black Power movement in Britain emerged in the late 1960s. It was inspired by radical anti-racist activism in the US and specifically by two high-profile visits. In 1965, Malcolm X, who advocated for Black empowerment ‘by any means necessary,’ visited London and the West Midlands. In 1967, a year after his declaration of ‘Black Power,’ Stokely Carmichael spoke in London. In the UK, different groups held various ideas about what liberation and self-determination for Black people might look like and how it could be achieved. The British Black Panthers (BBP) were the most effective of these organizations.

The BBP formed in 1968, two years after Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the US Black Panther Party. Leading members included Obi Egbuna, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Darcus Howe, Leila Hassan Howe, Olive Morris, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and their photographer Neil Kenlock. The group united people of African, South Asian, and Caribbean heritage. Neil Kenlock captured their activities and documented the wider community.

Black Power uprisings also took place in the Caribbean itself, notably in Jamaica in 1968 and Trinidad in 1970.

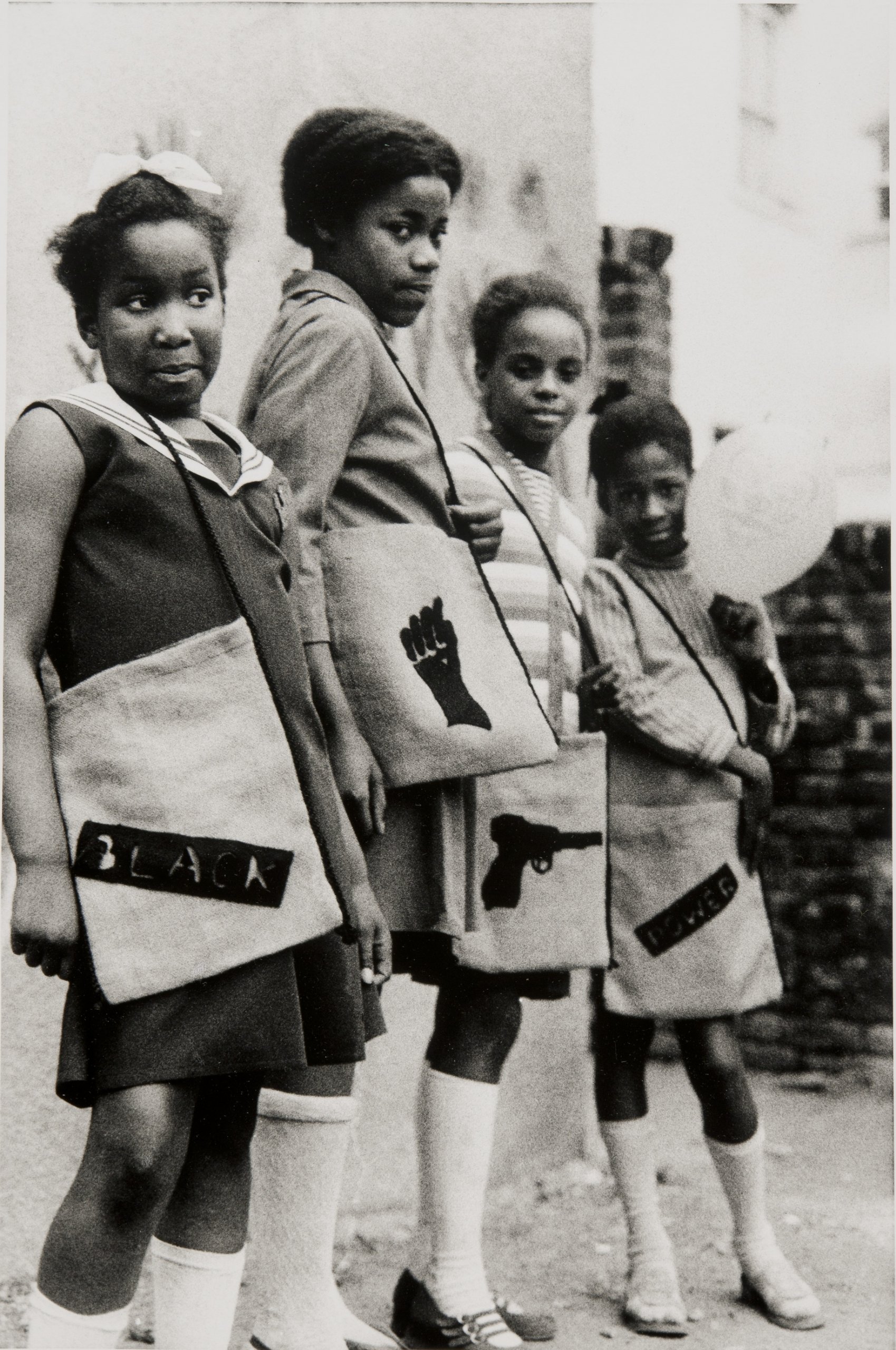

The rise of Black Power in Britain is shown in further works such as Neil Kenlock’s Black Panther school bags 1970.

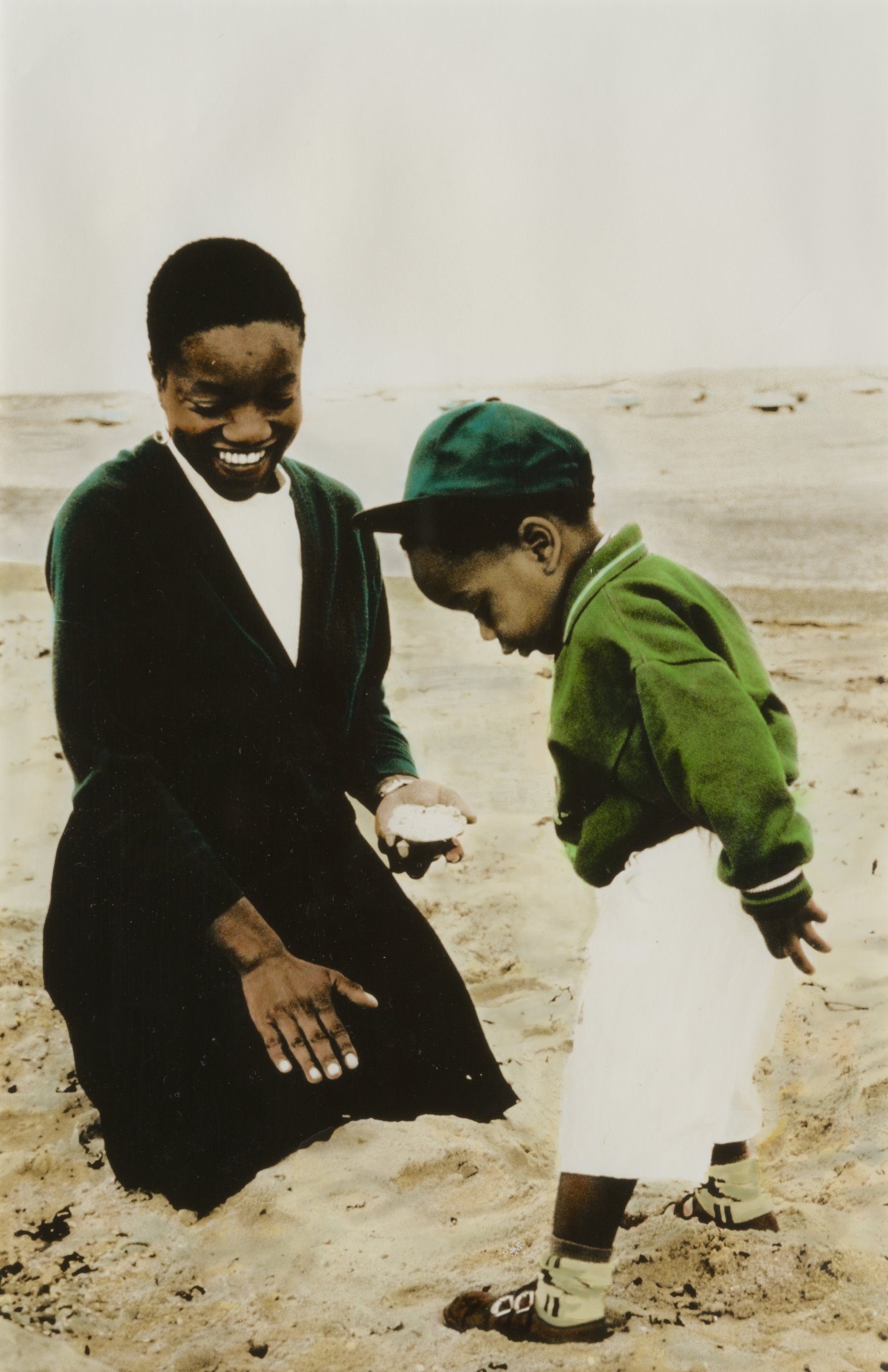

On the left, Frank Bowling’s Kaieteurtoo (1975) was made by pouring paint onto tilted vertical canvases. In 1989 Bowling returned to Guyana with his son, Sacha. During this visit, Bowling realized that his earlier abstract paintings evoking the Thames and English landscape traditions also referenced his birthplace. He then produced Sacha Jason Guyana Dreams (1989), seen here on the right. I think that’s a good reminder about the unconscious influences we all have, so we should resist presuming.

Works from the Black Art Movement of the 1970s and 80s depicted the social and political struggles faced by second-generation members of the Caribbean-British community. Photographs by Dennis Morris and Vanley Burke present everyday scenes of love, family, and social life in the midst of struggle and hardship.

Destruction of the National Front (1979-80) by Eddie Chambers, co-founder of the Bik Art Group, is the powerful series of four screenprints tearing up an image of the Union Jack seen below. In the 1970s, the National Front had turned the flag into a symbol for white supremacy. The artist reorganized the torn pieces into a swastika which is dismembered across four panels. The National Front were a far-right, fascist political movement that attacked and intimidated Black and Asian people in Britain. Their popularity peaked at the end of the 1970s.

The First National Black Art Convention was held at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in 1982. Organized by the Bik Art Group, it set out to debate ‘the form, functioning, and future of Black art.’ The event was a pivotal movement in the development of what is now known as the Black Arts Movement (BAM).

Major uprisings in the 1980s are explored in works such as Denzil Forrester’s Death Walk 1983, a tribute to Winston Rose, who died in police custody.

Tam Joseph’s The Spirit of the Carnival (c.1982) depicts a masquerader surrounded by police and a snarling dog. It was inspired by a scene witnessed at London’s Notting Hill Carnival. The work references the increasingly heavy-handed police presence at Notting Hill Carnival.

Joseph has said, “I wanted to show this figure… In Yoruba it’s known as Egungun… He’s a fun figure. He’s not menacing. But he is being contained by the police, and he’s looking for a way out.” Produced during a period of uprisings across the UK, Joseph’s costumed figure embodies the resilience and spirit of Black communities.

There are photos from the Black People’s Day of Action on 2 March 1981. And a reminder that it was the police’s Operation Swamp 81 at the start of April 1981 that caused the Brixton riots on 10–12 April 1981. Plainclothes police officers stopped and searched 943 black people in Brixton over six days.

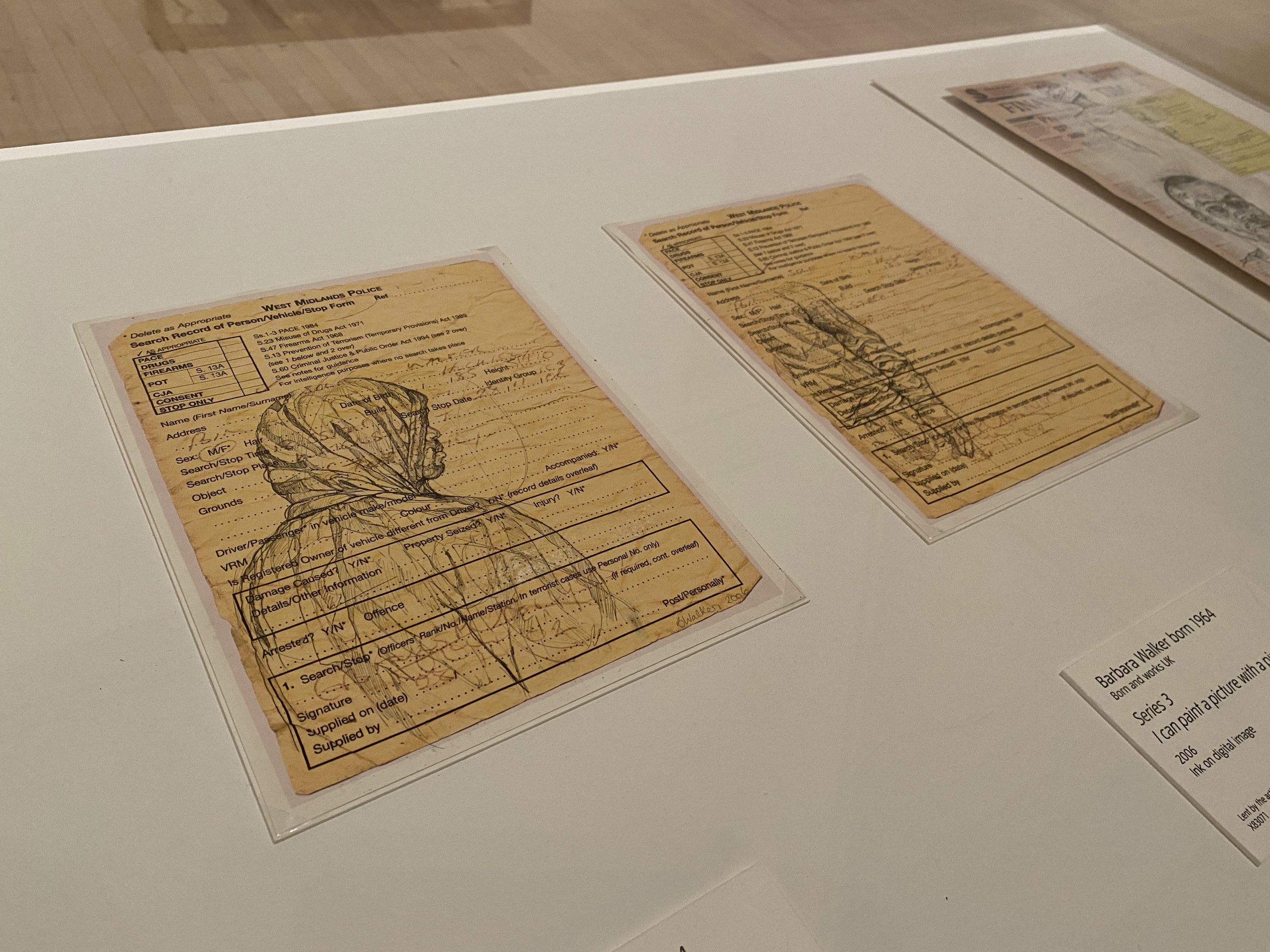

These 2006 drawings by Barbara Walker are portraits of the artist’s son drawn on photocopies of police forms handed to him each time he was stopped and searched in Birmingham. She wanted to recognize and highlight the young men who are still often judged by the way they look.

The Sky at Night (1985) by Tam Joseph depicts the Broadwater Farm Estate in Tottenham, north London. In October 1985, Cynthia Jarrett, a resident of the estate, died while police officers raided her home. The following day, demonstrations escalated quickly. A week after a further riot in Brixton, Tottenham saw a horrific night of violence. There were 230 police officers injured, and PC Keith Blakelock, assigned to protect firefighters, was killed.

The exhibition also includes a new iteration of Michael McMillan’s The Front Room, a reconstruction of a fictional 1970s interior, evoking the role of the home as a safe space for social gatherings at a time of widespread prejudice. You can see another version of this at the Museum of the Home.

For this installation, he has chosen a politically-engaged single woman as the occupant. Joyce’s Front Room has items that speak to issues of migration, religion, status, identity, and the transition from colonial to postcolonial. McMillan has said, “Colonialism meant that my parents’ generation saw themselves as British citizens coming to the ‘mother country.”

Ghosts of History

The artists in this room are associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1980s and early 1990s.

Ingrid Pollard’s Oceans Apart (1989) conveys the co-existence of the Caribbean and Britain, past and present, through intimate everyday scenes.

And Keith Piper’s Trade Winds (1992) is concerned with colonial history and its contemporary legacies. Computer-generated animation is shown on crates referencing both the commodities that enslaved Africans produced and the brutal way in which slavery reduced people to commodities.

Works by Lubaina Himid are included about François-Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803). He was enslaved until he was 45 and went on to lead the only successful revolt of enslaved people in modern history, known as the Haitian Revolution. (Lubaina Himid currently has a solo exhibition at Tate Modern).

Caribbean Regained: Carnival and Creolisation

The fourth chapter of the exhibition looks at the Caribbean as inspiration. Creolisation refers to the mixing of cultural influences and is a marker of Caribbean culture. Carnival is the most well-known example of creolization. Every Caribbean nation has its own version. We are told that Caribbean Carnival’s origins lie in enslaved people mocking the luxurious excesses of their enslavers.

Hew Locke’s work reflects on cross-cultural histories. The busts on display are made of Parian ware, porcelain designed to imitate marble. By using members of the British royal family as his subject, Locke’s cannibalisation of the figureheads of imperialism undermines their authority and transforms their identities.

The large-scale Peter Doig paintings are a delight. This is The Music of the Future (2002–2007).

I haven’t mentioned the video art here yet, but each was worth the time to watch. Paradise Omeros (2002) by Isaac Julien has a good narrative throughout. The Doig paintings are a collaboration between Doig and the Trinidad-based Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott (1930–2017). Julien’s film takes its title from Derek Walcott’s epic poem, Omeros (1990). Walcott is heard reading from the poem and seen gazing over the ocean in his native St Lucia, where Julien’s parents are from.

Lisa Brice often references the European history of painting. She reworks scenes by artists such as John Everett Millais (1829–1896) and Édouard Manet (1832–1883), which typify an objectifying male gaze. Situating these recognizable figures in new cultural contexts, Brice’s women appear empowered and autonomous. The works displayed here are set in a typical roadside bar in Port of Spain, Trinidad, except that the clientele is exclusively female. Their blue bodies relate to the artificial colors of nightlife and to Blue Devils, traditional Trinidadian Carnival characters.

Further excellent video art includes films by Ada M. Patterson. In one, she takes the form of a sea urchin, calling attention to the ecosystems of the Caribbean archipelagos. And in the other, the artist walked through Bridgetown, Barbados, draped in black fabric and a headdress adorned with urchin shells. The work comments on the experiences of bodies deemed out of place in the Caribbean, where many colonial-era anti-LGBTQI+ laws are still in effect.

Past, Present, Future

The exhibition ends with artists who have emerged more recently, many of whom revisit themes encountered earlier in the show. It includes new works created especially for the exhibition, including new designs by Grace Wales Bonner evoking the brass bands and parades of the Commonwealth Caribbean, Marcia Michael’s multimedia collaboration with her Jamaican mother connecting her voice and body to generations of history and memory, and a photographic installation by Liz Johnson Artur charting the early development of south London’s Grime music scene.

The final video is filmed on Super 8mm in 1992–97. Steve McQueen’s Exodus features two smartly dressed men carrying palm trees through the streets of London. The film is ironically titled after Bob Marley’s 1977 song of dislocation and return to the promised land. If you get the chance, do watch McQueen’s Small Axe (2020) – a series of five films that tell distinct stories about the lives of West Indian immigrants in London from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Conclusion

While I left the Hogarth and Europe exhibition irritated, I left this exhibition feeling I had learned something and enjoyed the discovery. When you leave, do have a look at the Caribbean-British Timeline: Art, Culture, and Society on the wall in the exhibition foyer. And there is an excellent book accompanying the exhibition.

Visitor Information

Exhibition Title: Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now

Location: Tate Britain, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

Dates: 1 December 2021 – 3 April 2022

Admission: £16

Official Website: www.tate.org.uk

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!