London has layers upon layers of history. Despite nearly two thousand-year of history, most buildings in London are only a few hundred years old, with many most famous buildings dating back to the Victorian Times.

That said, there’s so much history that has been completely swept away to time.

And that’s what Lost London by Richard Guard explores. It’s a small book that focuses on 150 lost aspects of London, from buildings, people and trades. They all get coverage as bits of London buildings or culture that has been lost to time.

It’s an interesting read and easily digestible as most articles are no longer than a page. You get the facts quickly. The book is not comprehensive, however, but it’s an excellent springboard for more research. I read about quite a few things I’d never heard of before that piqued my interest. I particularly love the lovely illustrations throughout the book.

Overall it’s a very enjoyable book and will make a great gift for the Londonphile in your life.

[amazon-product alink=”0000FF” bordercolor=”000000″ height=”240″]1843178036[/amazon-product]

Here’s a short excerpt:

Bedlam, or St Bethlehem’s Hospital – Liverpool street

There have been three separate sites for this most famous of mental hospitals. The first was at Bishopsgate, on the site of modern-day Liverpool Street railway station. Established in 1329 as a regular hospital run by the Priory of St Mary Bethlehem, by 1377 it was taking in ‘distracted’ patients.

Treatment was unsophisticated and often cruel, with inmates commonly chained, beaten, whipped and ducked.

With the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry v11i, ‘Bedlam’ fell under the control of Bridewell, a local prison. The already deplorable conditions for inmates continued to deteriorate. Eventually a grand new building was opened at Moorfields around 1675–76, designed by Robert Hook and with a front entrance adorned by two famous sculptures of Madness and Melancholy by Caius Cibber. These figures are all that remains of the second Bedlam and now reside in the Victoria & Albert Museum. A version of them can also be seen in the chilling final plate of Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress.

Much of the Hospital’s income was derived from admitting visitors to view the ‘idiots’. It became a popular holiday destination for many city dwellers over the next 100 years, until the practise was outlawed in 1770 as it ‘tended to disturb the equilibrium of the patients’. From then on, visitor numbers were controlled and sightseers had to buy a ticket in advance to get in.

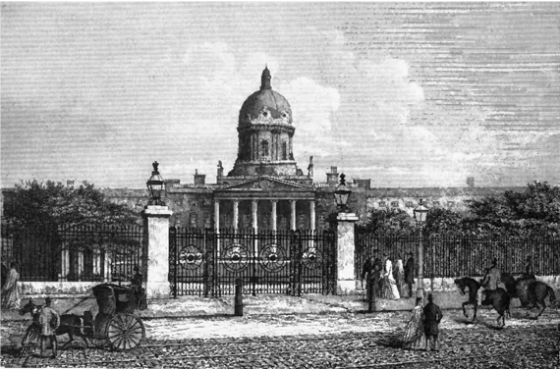

By 1800, Hook’s great building, once described as a match for the Tuileries Palace in Paris, was starting to decay, with the blame laid on cheap materials. So a new site for the hospital was found in St George’s Fields, Southwark (above). Patients were moved there in 1815 and conditions gradually improved. In 1851 a resident doctor was appointed, although the habit of viewing inmates remained ever popular. A balcony at the Grand Union pub on Brook Street was specially built to overlook the gardens and is still there to this day. The last patients left the institution in 1930 and the building was reopened in 1936 as the Imperial War Museum.

Text and images excerpted with permission from Lost London: An A–Z of Forgotten Landmarks and Lost Traditions (Michael O’Mara, 2012).

A Little Bit of London In Your Inbox Weekly. Sign-up for our free weekly London newsletter. Sent every Friday with the latest news from London!