William Morris (1834–96) was a man of many talents. His life, and life’s work, made a huge impact on the worlds of literature, design, and politics. When you hear his name, you may first think of the wallpaper and textile designs, but he achieved so much more. William Morris was a designer, architect, craftsman, artist, novelist, printer, socialist, environmentalist, idealist, and political thinker, as well as one of the most popular poets of his day. Morris’s work was influential in his own time and has left a legacy that still resonates strongly today.

Childhood

Morris’s paternal grandparents were Welsh, but his parents, William and Emma Morris, chose Walthamstow in northeast London for their family home (then in Essex). They had nine children of whom William was the third child and the eldest son to live to maturity.

He was born on 24 March 1834 at Elm House in Walthamstow. It was demolished in 1898 but there is a plaque on the fire station to note it was opposite. Elm House Dental Surgery (my dentist!) is opposite on the site of William Morris’s birthplace.

William Morris Senior was a financier in the City of London so the large family had an affluent Victorian household. Young William’s artistic enterprises were supported throughout his life.

Woodford Hall

In 1840, when William Morris was six years old, the family moved from Walthamstow to Woodford Hall. It was the success of his father’s investment in a copper mine in Devon that allowed the move to the impressive Georgian mansion. It was surrounded by 50 acres of land adjacent to Epping Forest.

William Morris had an idyllic childhood at Woodford Hall, and his time there was to be a formative influence throughout his life. He enjoyed fishing with his brothers, gardening in the Hall’s grounds and exploring the forest. He inherited his father’s fascination for the Middle Ages, which they both indulged through visits to Essex’s many parish churches and Canterbury Cathedral. He enjoyed riding his pony in the forest and was known to wear a miniature suit of armor – a gift from his parents. And their visits to Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge at Chingford Hatch awakened the young William to the wonders of traditional English interior decoration.

He was also a precocious reader, claiming to have started on the works of Sir Walter Scott at the age of four and to have completed the Waverley novels before he was nine.

In 1847, when Morris was 13 years old, his father died leaving the family in excellent financial circumstances, but no doubt deeply affected by his loss. The family then moved back to Walthamstow.

Woodford Hall was demolished in 1900. The Woodfield Memorial Hall (Woodford High Road, E18) was built on the site and opened in 1902. It has a plaque as a reminder to the former home of William Morris.

Before the grand building was destroyed, Woodford Hall was the Catherine Gladstone Free Convalescent Home from 1869 to 1900. Catherine Gladstone (1812–1900) was the wife of the then Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone (1809–1898). She was involved in caring for the sick admitted to the London Hospital during a cholera outbreak, and Woodford Hall was acquired to house the orphans. The Home offered places to non-contagious and non-infectious women and children of the East End who were well enough to be discharged from the London Hospital, but were still weak and likely to benefit from fresh air and a nourishing country diet.

Chapel le Frith, Woodford Hall’s chapel, was not demolished and is a private home at 57 Buckingham Road, E18 2NH. It was likely added when the Hall became a hospital.

Education

While living at Woodford Hall, from the age of nine, Morris attended a small local school: Misses Arundale’s Academy for Young Gentlemen. After the family moved back to Walthamstow, Morris started at Marlborough College, in Wiltshire, from February 1848. This was a new public school for the sons of the emergent Victorian middle class. Morris received a classical schooling but was unhappy and felt isolated. He disliked learning by rote and argued that children should acquire practical skills as well as intellectual knowledge, and that education should be lifelong. Life at Marlborough College was prone to violence and a serious riot broke out in 1851. He was then able to leave and completed his secondary education with a private tutor; the Reverend Frederick B. Guy, Assistant Master at the nearby Forest School, in Walthamstow.

Water House

After his father died, the family resettled in Walthamstow in a smaller (but still substantial) Georgian villa called Water House. This was William Morris’s home from 1848 to 1856.

The building is now the William Morris Gallery and what was his home’s garden has been a large public park called Lloyd Park since 1900. The building’s blue plaque for William Morris also notes that the building was the home of Edward Lloyd, the publisher from 1857 to 1885.

I like the Gallery and have visited often. In 2015, I was able to join a sleepover for families and we got to stay on the top floor overnight. The room where we slept had panelling that is thought to date from the mid-sixteenth century. It was probably removed from earlier houses in the area and reused in Water House; a common practice in the eighteenth century. Some original glass remains in the windows in this room.

There is one more plaque for William Morris in Walthamstow at the William Morris Hall on Somers Road. The Hall was financed by local subscription and erected by voluntary labor in 1909 by members of the William Morris Co-Operative Society as a “Home” for the Socialist/Trades Union/Co-Operative Movement in Walthamstow.

And Walthamstow Central, has a William Morris design on the platform tiles.

Oxford

In June 1852 he took Oxford matriculation and he entered Exeter College in January 1853. His experiences in the halcyon medieval city were all to shape his artistic, professional and social life.

At Oxford he developed his interest in art and architecture and met his life-long friend, Edward Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones introduced Morris to his school friends from Birmingham – Charles James Faulkner, Richard Dixon and William Fulford – and all of the men were committed students of theology. However, after a few months at Oxford, Morris and Burne-Jones visited northern France and Belgium, where they reveled in the glories of miniaturist detail in medieval painting and the grandeur of Gothic architecture. They then decided to give up their aspirations to the clerical life and devote themselves to art.

Morris chose to return to his childhood love for architecture, while Burne-Jones found his calling as a painter. Once he had graduated from Oxford, Morris joined the firm of G. E. Street, which had designed the magnificent Gothic Revival Law Courts in London. In Street’s office he made the second of his intimate and lifelong male friendships, with Street’s senior clerk, the architect Philip Webb.

Burne-Jones sought out the leading Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti as his mentor. Morris also became a Rossetti acolyte and strove to become a painter as well.

Burne-Jones had moved to London and William Morris moved to the capital as well when the G.E Street architectural practice moved from Oxford to London in August 1856.

Bloomsbury

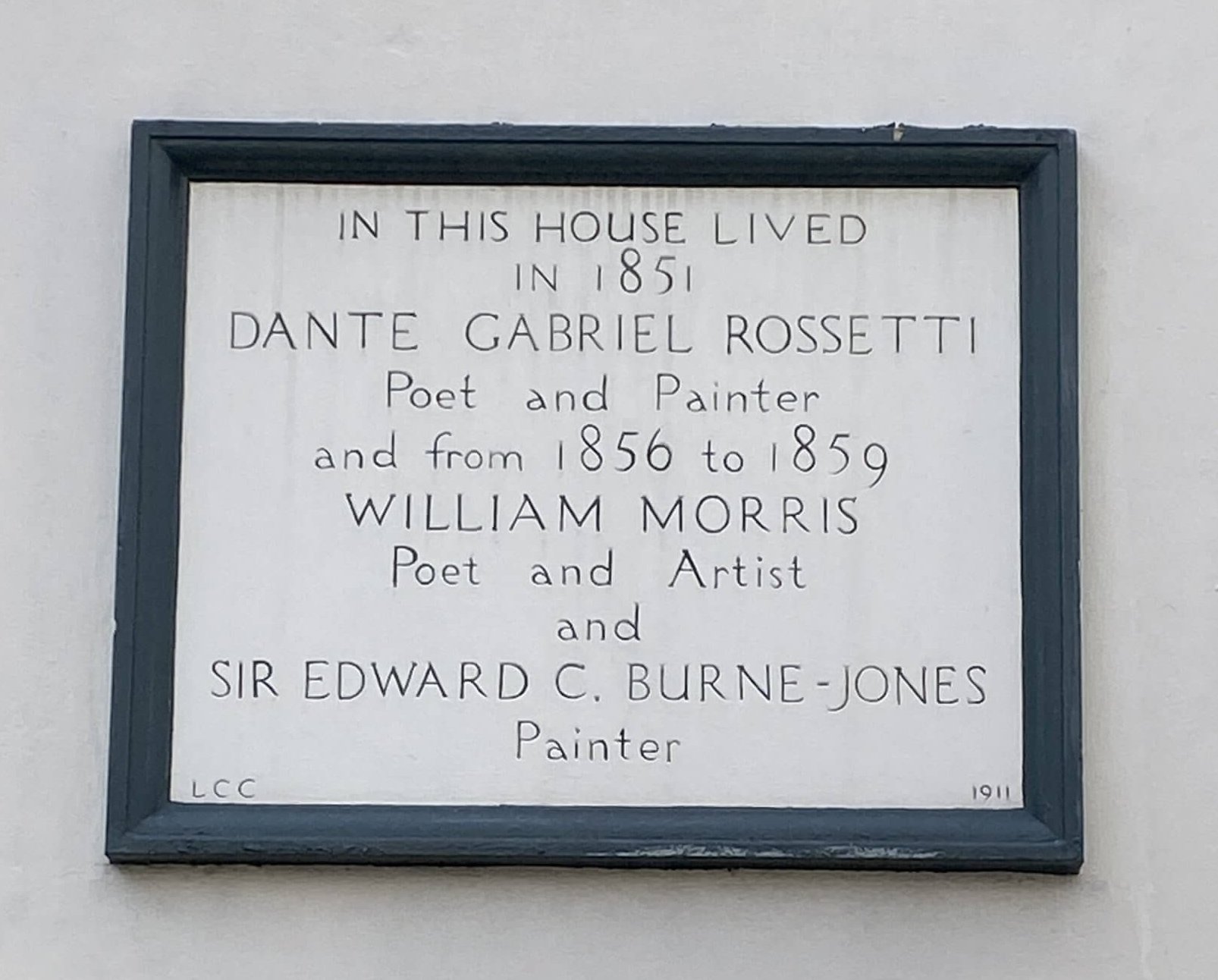

In 1848, seven artists and critics formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. On Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s behalf, Thomas Woolner, the only sculptor of the Pre-Raphaelite Brothers, enquired about lodgings on the first floor of 17 Red Lion Square, Bloomsbury. The three rooms were available at 20 shillings per week (roughly £80 today). There was a stipulation from the landlord, however, when he understood that artists were interested in his rooms, that the models were to be kept under “gentlemanly restraint” because in his opinion “some artists sacrifice the dignity of art to the baseness of passion.” Stipulations considered, Rossetti and Deverell took up residency in 1851, and lived there for a brief spell of six months.

Widening the circle of the PRB in November 1856, Rossetti suggested to Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris that they take his former lodgings. For three years the two artists resided at 17 Red Lion Square. The Square would have looked quite different as the garden in the center of the square was added later in 1885.

During their time at no.17, their maidservant, Mrs. Mary Nicholson, became known as ‘Red Lion Mary’, and by all accounts put up with the bizarre and sometimes demanding behavior of the two and their friends with great humor and loyalty.

At 17 Red Lion Square, William Morris was inspired to design several pieces of furniture for his bachelor pad. Burne-Jones wrote, ‘Topsy (Morris) has had some furniture (chairs and table) made after his own design; they are as beautiful as medieval work, and when we have painted designs of knights and ladies upon them they will be perfect marvels.’ Rossetti was invited to help in the decoration of a solid, rustic chair, christened the Arming of the Knight chair due to the scene he painted on it.

Some of the pieces designed by Morris for Red Lion Square now reside in museums around the world: the rustic round table can be seen at The Wilson – Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, the Arming of the Knight Chair painted by Rossetti now lives in the Delaware Art Museum and a large settle also designed for no.17 occupies Red House, Morris’s next home in Bexleyheath.

After leaving the Square in 1859, William Morris returned in 1861, to no.8 Red Lion Square, with some of the other Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood members to establish the headquarters of what would eventually be known as Morris & Co. Morris’s personal and professional association with this part of Bloomsbury would continue for the next 25 years.

Oxford Frescoes

In 1857, Rossetti was commissioned to supervise decorative work in the debating hall of Benjamin Woodward’s new building, which was used by the Oxford Union Society. He enlisted his friends for this task and the group (which included the artist Arthur Hughes, amongst others) painted frescoes illustrating scenes from Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Regrettably, the wall had not been prepared correctly and within a year the decoration had faded unrecognizably. As the fresco project drew to a close in 1858, and as Morris had finished long before the others, he published his first volume of poetry, The Defence of Guenevere.

The Oxford frescoes helped Morris realize his vocation more clearly. And it was during this period, Morris met his future wife, Jane Burden.

Marriage

It was Rossetti who had first noticed Jane Burden, seated near them in a local theatre, and persuaded her to model for the frescoes. At 17 years old, she typified the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of female beauty, with her dark wavy hair, soulful eyes and her paleness. Originally she modeled for Rossetti. Morris then used her as his model for La Belle Iseult, the painting now in the Tate collection, his only surviving work in oils.

Morris fell deeply in love with Jane and his old Oxford friend, Richard Dixon, who had taken his Holy Orders, married the couple on 26 April 1859 at St Michael’s parish church in Oxford. The honeymoon was spent in Bruges, Belgium.

Their initial happiness did not last but they remained together until Morris’s death. Rossetti had been fascinated by another young working-class woman, Elizabeth Siddal, whom he married in 1860. But when she committed suicide two years later, his attraction for Jane was gradually reawakened. When Jane became involved in a relationship with Rossetti, he and Morris took on the lease of a house at Kelmscott in Oxfordshire, providing a refuge for Jane and the two children, and a place where she and Rossetti could be together away from the public gaze.

Red House

In 1859, Morris commissioned his friend and colleague from Street’s offices, Philip Webb, to create the couple’s first home, Red House. They moved in in 1860. It was the only house William Morris owned as all the other places he lived were rented.

Morris had received an annuity of £900 a year upon his father’s death and could therefore afford to create this lavishly decorated and thoughtfully designed villa in Bexleyheath, near London. Using local materials, and modeled on an English cottage, it had steep tile roofs, tall chimneys and was built in brick. Webb and Morris designed every piece of furniture, glass, tile-work and embroidery. The L-shaped house lay along the ancient pilgrims’ route to Canterbury and Morris cast himself in the role of genial Chaucerian host. He encouraged the stream of artistic guests to join in the process, creating the ultimate Arts and Crafts collective art work.

The blue plaque here notes that Morris lived at Red House from 1860 to 1865. The Bexley Civic Society added another commemorative marker nearby in 2000.

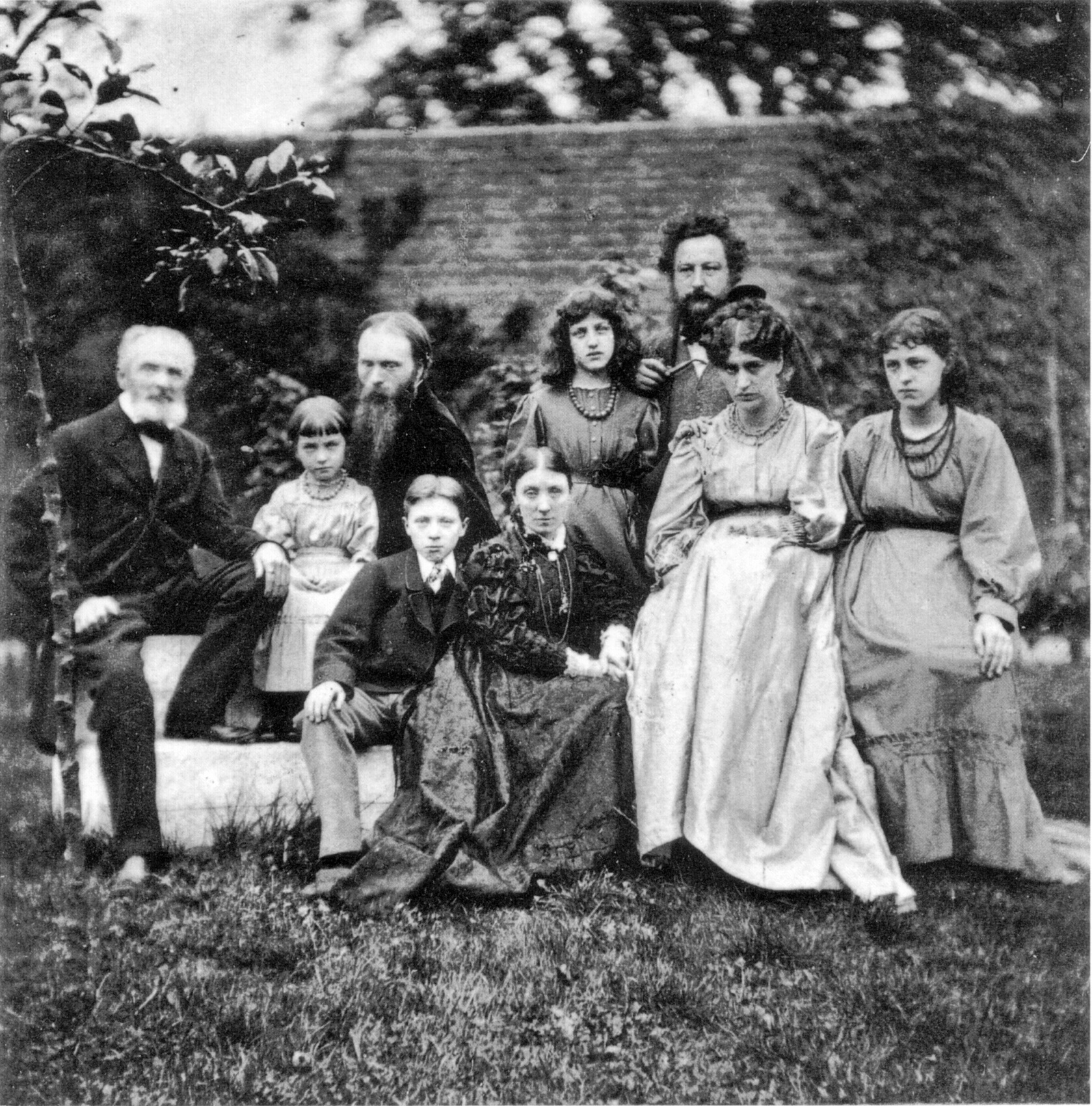

The Firm

William Morris’s decorating company – originally Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. – was founded in spring 1861. Unofficially, it was referred to as the Firm. Peter Paul Marshall, a surveyor and sanitary engineer, and Charles Faulkner, who had given up a mathematics fellowship to do the book-keeping, provided the firm’s managerial resources. Other non-titular founder members included Philip Webb, Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelite painters Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti. Many of these artists’ female relations also created and executed designs: Kate and Lucy Faulkner and Georgiana Burne-Jones painted ceramics, while Jane Morris and Elizabeth Burden created much of the embroidery. For additional staff, they employed boys from the Industrial Home for Destitute Boys in Euston; many of whom were trained as apprentices.

The Firm’s first headquarters were at 8 Red Lion Square, Bloomsbury, using the first floor as offices and showroom (the building is no longer there). In the attics on the third floor were the workshops and in the basement, was a furnace for firing glass for stained-glass windows and tiles. Rossetti referred to the building as, “the Topsaic laboratory” as Morris was nicknamed Topsy or Top by his friends. (The nickname was after the little slave girl in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin because of Morris’s uncontrollably curly hair.) Philip Webb had a workshop and home at 91-101 Worship Street, EC2 from 1862.

The Firm created painted furniture, mural decoration, metalware and glass, embroidery and hangings, jewelry, and hand-painted tiles although it was soon clear that stained glass for new and restored churches was to be the lynchpin of their work in the early years. The Firm first exhibited in the Medieval Court at the International Exhibition at South Kensington in 1862. They were awarded two gold medals and a special jury mention for the color and design of its stained glass. As a result, the firm received its first big commission. G. F. Bodley selected the company to design and make the stained glass windows for the many churches he had designed in Gloucestershire, Brighton and Scarborough and All Saints’ Church and Jesus Chapel in Cambridge. Despite Morris’s anti-elitist ethos, the Firm became increasingly popular and fashionable with the bourgeoisie.

At this point Morris focused his energies on designing wallpaper patterns, the first being ‘Trellis,’ designed in 1862. From 1864, Jeffrey and Co. of Islington carved Morris’s patterns into pear wood blocks that were then hand-printed. Morris excelled in the design of wallpapers that he described as recreating the charm of the forest inside the home.

By 1864, the exhaustion of daily commuting (3–4 hours daily) and his own financial problems, caused by decrease in value of his family shares, forced Morris to sell Red House. The building remained in sympathetic private ownership until its acquisition by the National Trust (for £2 million) in January 2003.

In November 1865 Morris and his family moved to no.26 Queen Square in Bloomsbury – the same building that the Firm moved its base of operations to earlier in the summer – so he was, literally, living above the shop.

Queen Square

The Firm occupied the house at no.26 Queen Square for the next 17 years. An office and showroom formed the ground floor and there was a large workshop in the rear in what had previously been the ballroom of the large house. In a court at the back were other small workshops as well as a kiln. When Faulkner left, Warrington Taylor was employed as a business manager and stayed with The Firm until 1866.

In 1866, the firm received two important private commissions. Firstly, the redecoration of the Armoury and Tapestry Room in St. James’ Palace, and the design and decoration of the Green Dining Room in the South Kensington Museum (now the Morris Room at the Victoria and Albert Museum). This popularity, and the life of comfort in which it allowed Morris to indulge, was to trouble both him and art historians, for it ran counter to his avowed socialist aims of useful and beautiful objects affordable to all.

In 1881 the National Hospital took over the remainder of the lease at 26 Queen Square for the sum of £3000 and The Firm moved premises to Merton Abbey. Today the building forms part of The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery.

Kate Middleton’s interior designer, Ben Pentreath, lives at 6 Queen Square. In 2020, he collaborated with Morris & Co to recolor original wallpaper and fabric designs for a new collection called The Queen Square Collection.

Unwanted Attention

By the late 1860s, the relationship between Morris’s wife, Jane, and Rossetti was gaining attention. William Morris was a ‘celebrity’ by this time and reluctantly sat for a portrait by George Frederic Watts in 1870.

Morris had grown to accept his wife’s affair, and found an amicable way of staying together.

Kelmscott Manor and Rossetti

In 1871, Morris and Rossetti took a joint tenancy on Kelmscott Manor in the village of Kelmscott, Oxfordshire. Morris wanted his children to have a home away from the city’s pollution and he loved the sixteenth-century building. Morris divided his time between London and Kelmscott so he didn’t have to be there as much when Rossetti was there.

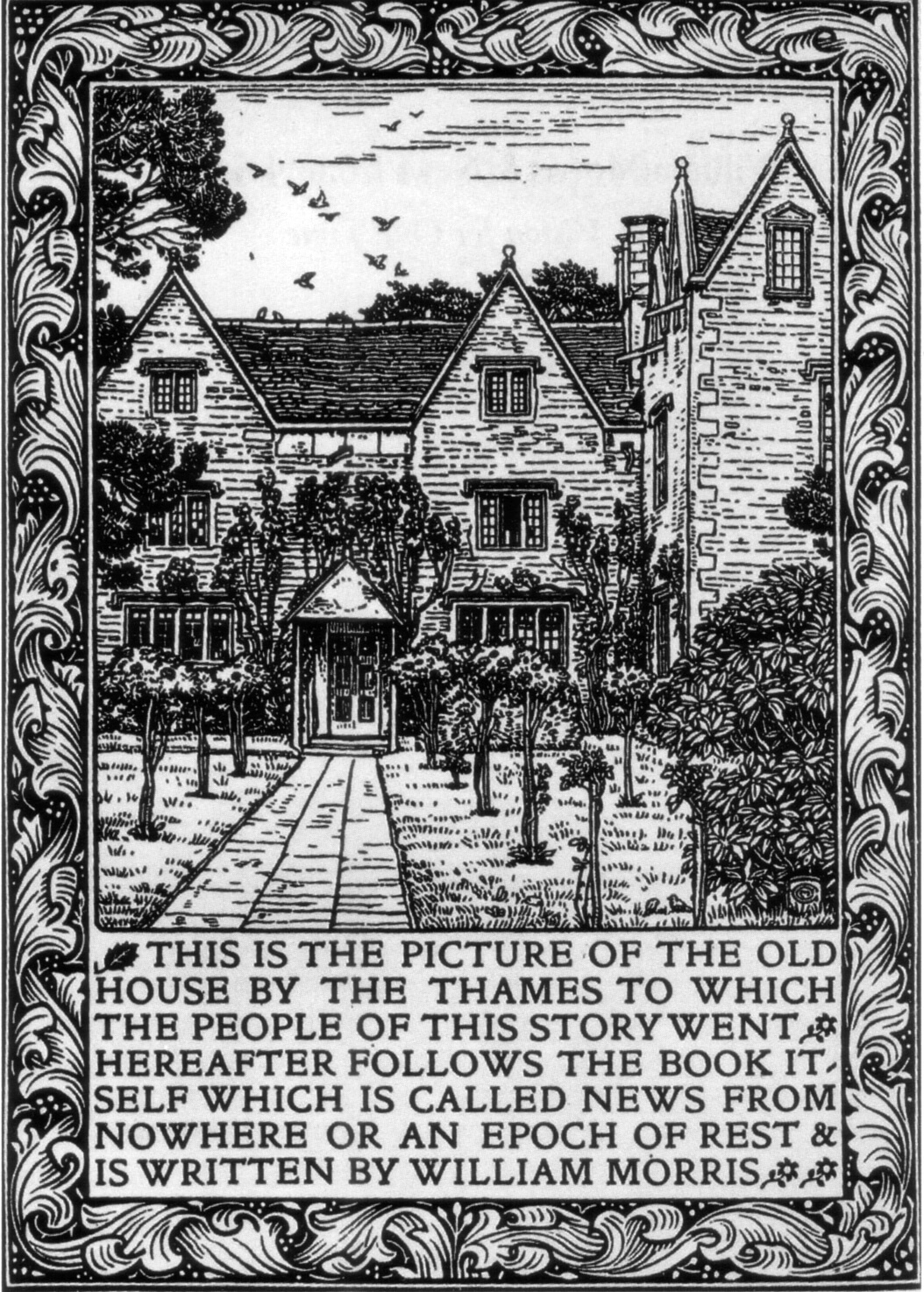

Morris used Kelmscott Manor as the cover for his utopian novel, News From Nowhere, published in 1890.

In 1873, Morris also took on a new London house for the family. Although retaining a personal bedroom and study at Queen Square, he relocated his family to Horrington House in Turnham Green Road, Chiswick (now demolished). This allowed him to be closer to Burne-Jones’s home and the pair met on almost every Sunday morning for the rest of Morris’ life.

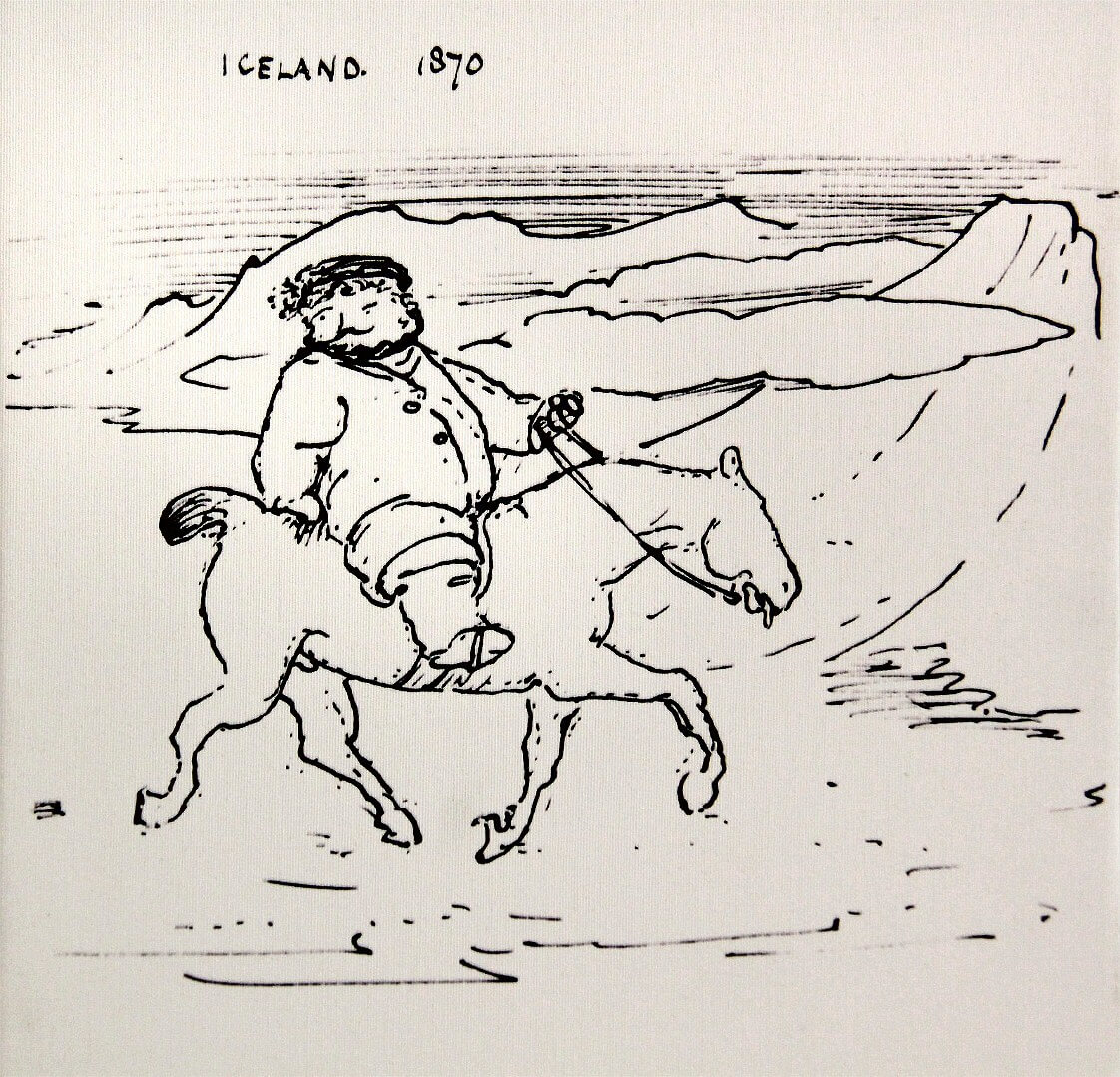

Iceland

Morris had become fascinated with the Norse legends of Iceland in the 1870s. He met the Icelandic scholar Firikr Magnusson in 1862, when he had visited Britain to supervise the publication of a Norse New Testament and Dictionary.

In July 1871, not long after moving into Kelmscott Manor, Morris left Jane and their daughters with Rossetti and went to Iceland. He traveled across the country by horse for a couple of months before returning in September. While there he experienced a reawakening of his social conscience when he witnessed the simple dignity of classless life amidst the unrelenting hardships experienced in Reykjavik.

Morris & Co.

Rossetti wasn’t happy at Kelmscott and eventually suffered a mental breakdown. As he slid into mental instability, and Marshall and Faulkner became somewhat apathetic, Morris decided to buy out their shares in the firm for £1,000 each.

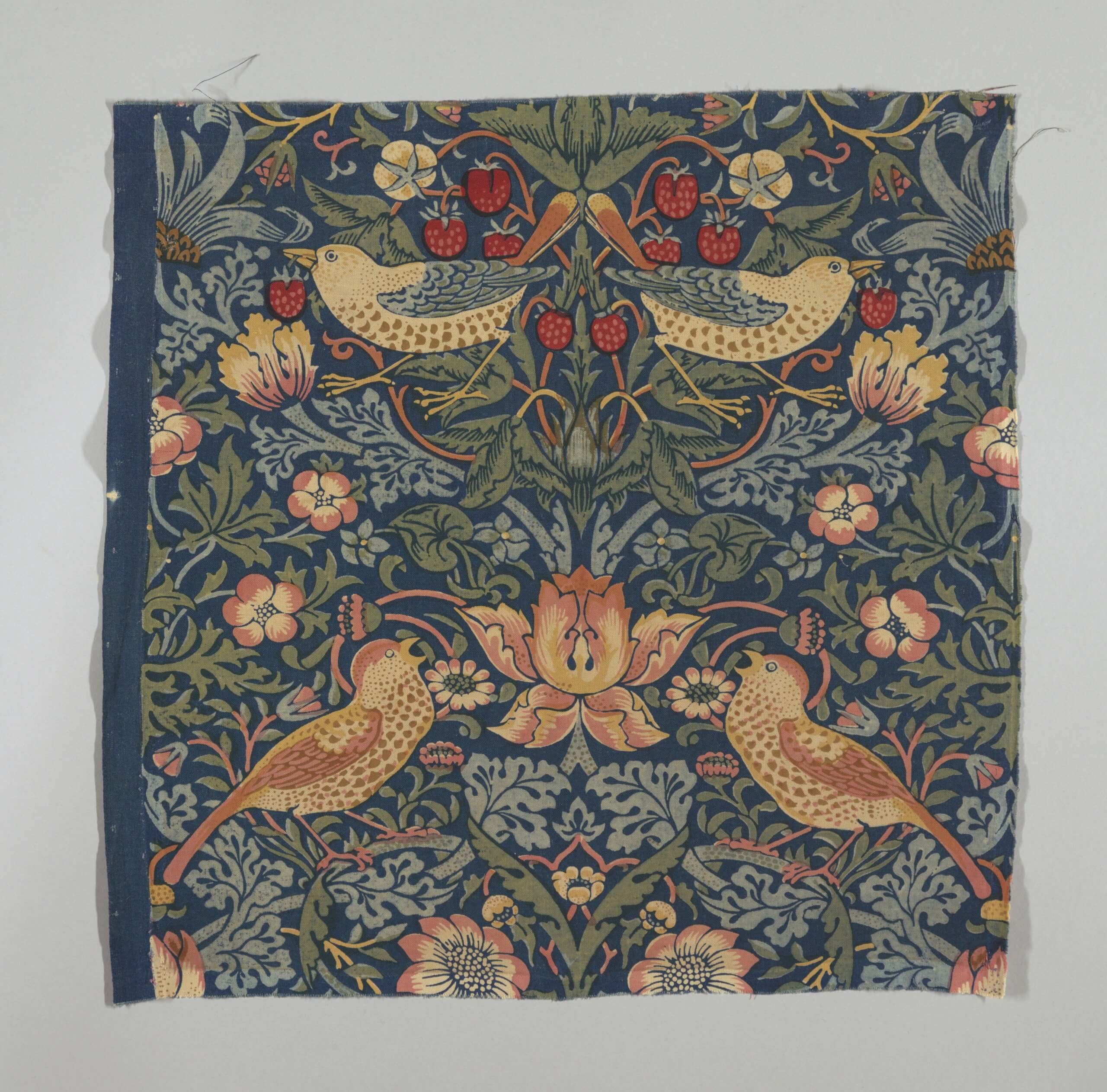

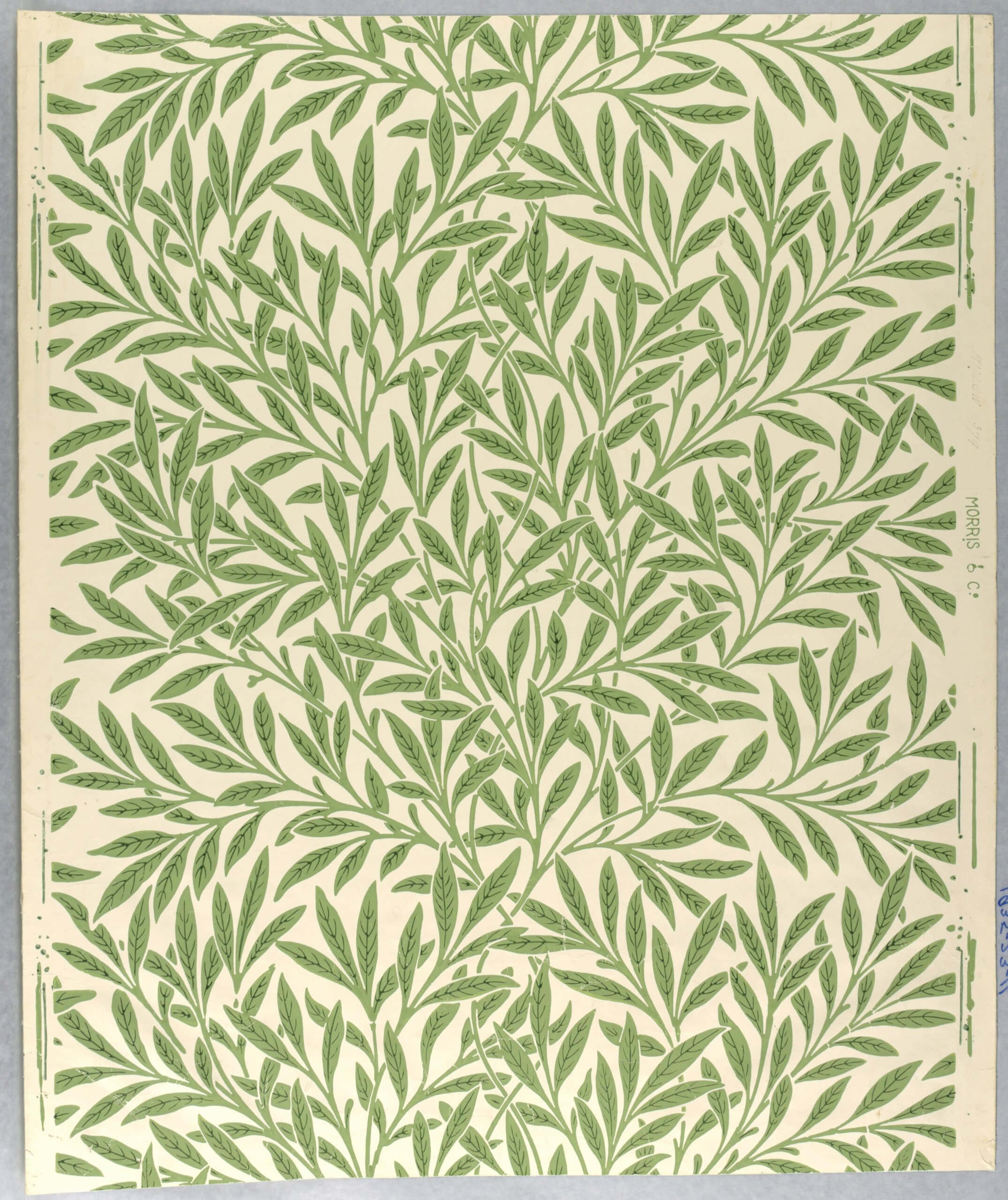

In 1875, Morris and Co. was formed, with only Burne-Jones, Philip Webb and himself providing the designs. Over the next seven years, Morris was to create the multitude of wallpaper and textile designs for which he is best remembered.

Morris drew direct inspiration for many of his wallpaper and textile designs of the 1870s and early 1880s from the garden at Kelmscott Manor. ‘Strawberry Thief’ came about after he saw thrushes stealing the fruit from underneath the strawberry nets.

And the best known of all Morris’s patterns, ‘Willow,’ derives from the leaves of the trees that edged the river where Morris used to fish for gudgeon and perch.

Morris was always very hands-on and he learned natural textile dying methods from Thomas Ward in Leek, Staffordshire, disconcerting his friends by returning to London with his arms dyed blue. He also experimented personally with both machine and hand-weaving techniques.

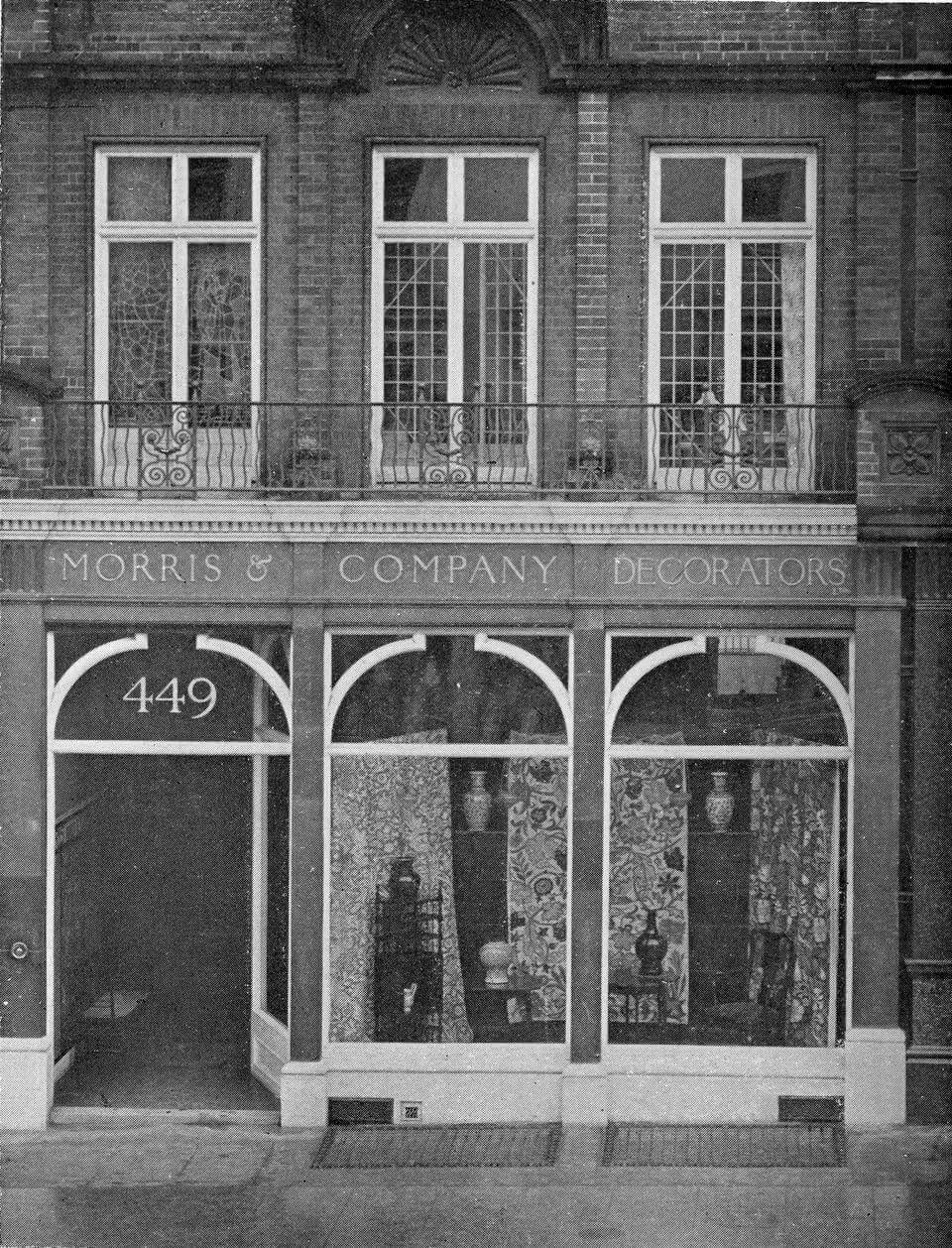

Oxford Street

In 1877, the firm opened a new showroom on Oxford Street as a sign of the company’s success. It was at 264 Oxford Street but the building was re-numbered 449 in February 1882 and is now opposite Selfridges.

Morris also used the showroom as a meeting place for the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) on 7 June 1877. He became deeply critical of the concept of restoration that allowed for wholesale reconstruction rather than conservation, such as the work of Sir George Gilbert Scott at Tewksbury Abbey and at Oxford Cathedral. After Morris formed SPAB, known as Anti-Scrape, Morris & Co. refused all further commissions for new stained glass in original medieval churches.

The business moved to 17 St George Street, W1, in 1917 and the William Morris Gallery has this wonderful illustration of the showroom in a 1919 pamphlet.

Kelmscott House

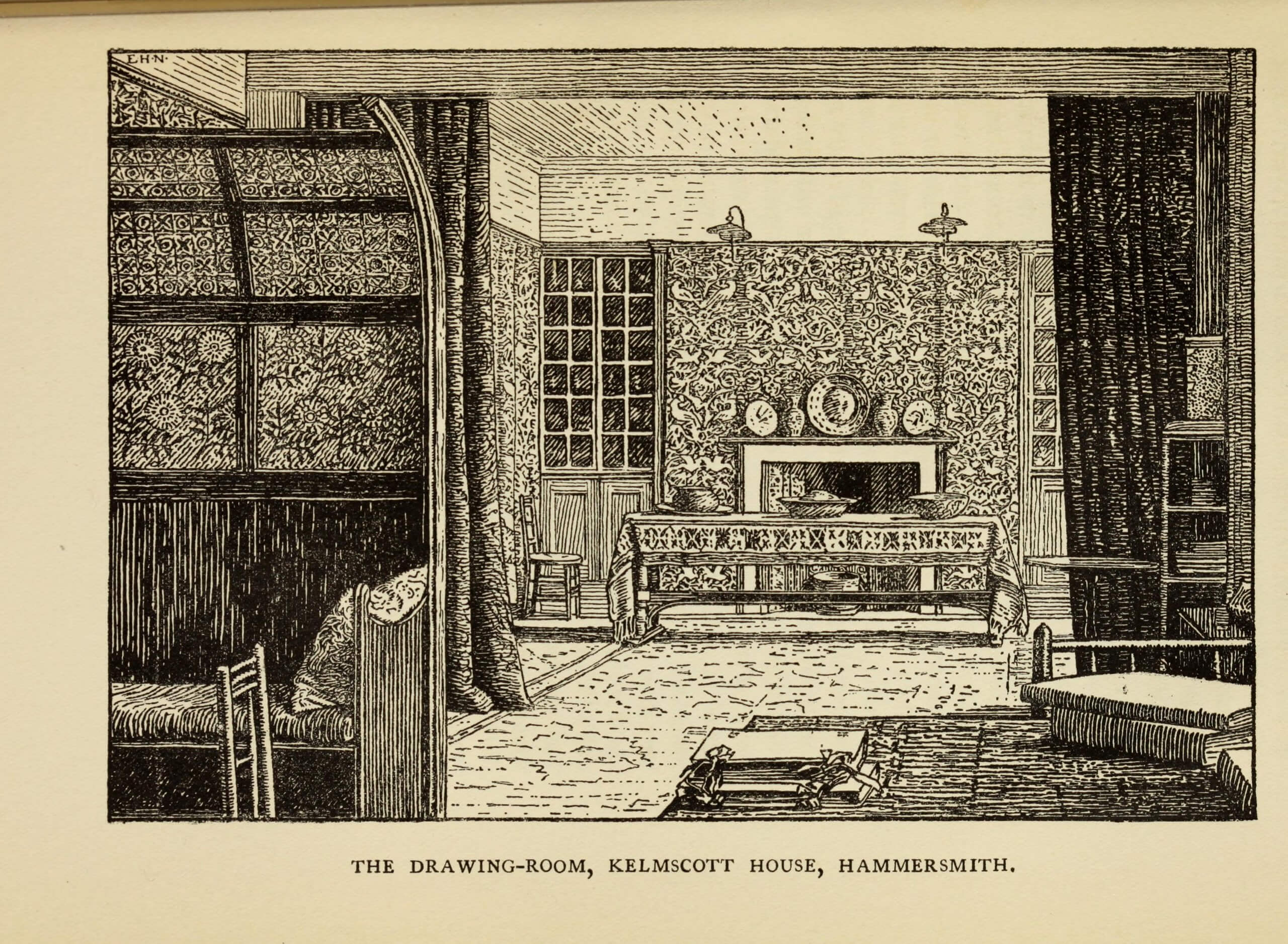

A year later, in 1878, Morris moved into Kelmscott House; an eighteenth-century brick house overlooking the Thames in Hammersmith (leaving Kelmscott Manor, in Oxfordshire, for his wife, Jane, and Rossetti).

At 26 Upper Mall, the property was built around 1790. It originally shared grounds with 22 and 24 Upper Mall that stretched all the way to King Street. No.24 was rented by Catherine of Braganza (wife of Charles II and Queen of England) for her household when she lived in the adjoining estate and it originally formed one dwelling with no.22.

William Morris lived at Kelmscott House from 1878 until his death in 1896 even though he disliked Georgian architecture. He changed the name from The Retreat to one that reflected his happy association with Kelmscott Manor.

The William Morris Society was founded in 1955 to make the life, work and ideas of Wiliam Morris better known. Today, the main house is a private family home (leased from the Society), while the basement rooms and the coach house are the Society’s headquarters. These rooms offer a fascinating glimpse into Morris’s political and creative activities during his final years.

If you decide to visit, do combine the trip with the nearby Emery Walker’s House. The House includes one of the largest collections of hand-blocked Morris & Co. wallpapers in situ in the world, plus an outstanding range of textiles and embroideries. While he is not such a well-remembered name, Emery Walker was central to the Arts & Crafts movement. William Morris “did not think the day complete without a sight” of his friend, Emery Walker.

William Morris’s younger daughter, May Morris, lived next door to Emery Walker at 8 Hammersmith Terrace. She was good friends with Dorothy Walker, Emery’s daughter. May was an influential designer and director of the embroidery department at Morris & Co. George Bernard Shaw, the playwright, also lived there with May and her husband for many months, to the detriment of May’s marriage. (Those arty ‘fluid’ relationships, eh?)

(William Morris’s elder daughter, Jane, known as Jenny, stayed with her mother as her epilepsy meant she needed care. There are some lovely family photos in the National Portrait Gallery collection.)

On the ground floor of the coach house at Kelmscott House, May Morris employed local women to weave her first carpets, the Hammersmith rugs.

As the textile side of the company’s work became their dominant products, Morris & Co, moved its operations to Merton Abbey, a group of buildings originally used for printing, in north Surrey on the River Wandle.

Morris believed in quality products without exploiting those who made them. The machine produced objects of the Victorian age were, according to Morris, ugly and non-functional because they reflected the immoral work practices of the modern factory which alienated the craftsman from his sense of creative satisfaction and were driven by capitalist competition rather than co-operation. He wanted everyone to have access to beauty as he felt beauty could transform lives. His workshop at Merton Abbey was built to be a healthier place to work than other Victorian workplaces. Staff worked fewer hours and younger members of staff were given free schooling. He paid his workers higher than average wages, supplied a library for their education, a dormitory for the apprentice boys and provided work in clean, healthy and pleasant surroundings.

Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.

William Morris – The Beauty of Life, 1880

Socialism

William Morris felt strongly that art could not flourish in a society of “commercialism and profit mongering” and that Socialism was “…the only hope of the arts”. He strove for socialist ideals, both through his various initiatives to create artistic communities inspired by medieval guilds and, in later life, through his writings, lectures and marches working for the socialist cause.

His time in Iceland helped him to imagine a neo-medieval utopian society. Several groups of artists sought to recreate the collective labor of the medieval guild, and Morris was instrumental in forming the Art Worker’s Guild in 1884 and the Art and Craft Exhibition Society in 1886.

Morris joined, and became dissatisfied with, numerous political organizations. He, like Gladstone, Tennyson, Carlyle, Trollope, Darwin and Ruskin, joined the Eastern Question Association, which spoke against the Turkish atrocities in the Bulgarian uprising of 1876. As its Treasurer, Morris wrote a letter to the Daily News and then a pamphlet entitled Unjust War: To the Working Men of England. However, he became disenchanted with the Association, as it became clear that it was largely uninterested in improving the living conditions of the British poor.

Morris then became Treasurer of The Liberal League that helped to motivate Gladstone’s electoral victory in 1880. However, once in office, the Liberal government was to disappoint him as well and once again Morris resigned.

Henry Mayer Hyndman’s Social Democrat Federation appeared to express Morris’s position more fully, so he joined in 1883. He wrote articles for, and personally distributed, its newspaper Justice. When the Federation became beleaguered in the slow process of parliamentary reform, Morris and ten leaders of its executive formed the Socialist League, one of the strongest advocates for a socialist revolution in 1880s Britain.

Few of Morris’s friends empathized with his Socialism except Webb and Faulkner, thus he made new friendships, most notably with the Russian émigré anarchist Prince Kropotkin and Friedrich Engels. After the bloodshed on the Bloody Sunday march in 1887 and his removal by the anarchist wing from the editorship of The Commonweal, the League’s weekly paper, Morris resigned in 1890. He created the Hammersmith Socialist Society, through which he sought to reconcile these two disparate strands of parliamentary and anarchist socialism.

During this project, Morris crystallized his socialist theories of the inseverable link between a society and its art, which he set out in Hopes and Fears of Art of 1882, an anthology of lectures which he gave in Working Men’s clubs to raise funds for Anti-Scrape.

The Writer

Morris was a prolific writer of poetry, fiction and essays. The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine published his first literary efforts in the 1850s.

He published six volumes of poetry starting with The Defence of Guenevere (1858). When Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co. was experiencing financial crisis in 1867, Morris returned to writing as a form of escape, producing his epic poem about the search for the Golden Fleece, The Life and Death of Jason. This success was followed by his most lengthy and popular poem, The Earthly Paradise (1868-70). It recounted 24 legends from every cultural tradition, the East, Iceland and his first love, medieval romance, and it brought him almost immediate fame and popularity. This was followed by Love is Enough (1873), Sigurd the Volsung (1876) and Poems by the Way (1891). Later, Morris wrote less original poetry but found time to translate the Aeneid, the Odyssey and Beowulf. He was approached with an offer of the Poet Laureateship after the death of Tennyson in 1892, but declined.

Morris articulated his socialism not only through his published lectures, but also in his prose Works, His Socialist romances, The Pilgrims of Hope and The Dream of John Ball and his futuristic utopian novel News from Nowhere appeared in serialized form in The Commonweal between 1885 and 1890.

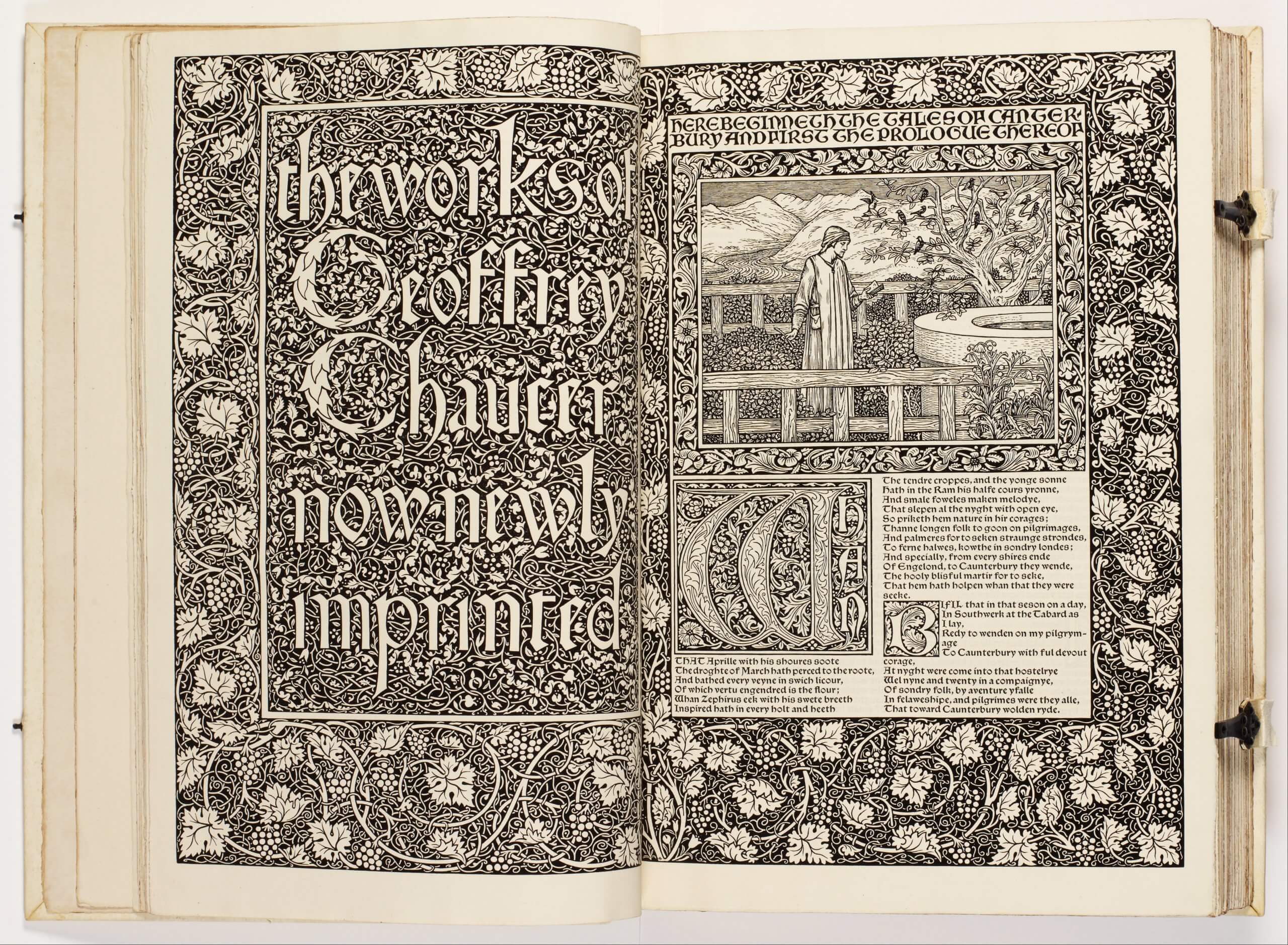

The Kelmscott Press, which printed and bound fine books, grew out of a range of inspirations. Georgiana Burne-Jones, who no doubt provided Morris with great comfort in the 1870s, being aware of the pain of straying marital partners herself, inspired Morris to create some of his most exquisite illuminated manuscripts, The Book of Verse and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The Kelmscott Press combined the dual trends of lavish illustration and neglected Early English texts. It published 53 exquisitely illustrated books between 1891 and 1898, the most famous of which is The Kelmscott Chaucer which has 87 woodcuts by Burne-Jones and decorations by Morris.

His novel, The Wood Beyond the World, is considered to have heavily influenced C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series. J.R.R. Tolkien was inspired by Morris’s reconstructions of early Germanic life in The House of the Wolfings, and James Joyce also drew inspiration from Morris’s work.

Conclusion

While Morris and his ideals typify the aspirations and dilemmas of Victorian Britain in microcosm, his importance in shaping twentieth-century culture cannot be overestimated. His popularity reflects the timeless relevance of the man and his thinking.

When he was dying one of his physicians diagnosed his disease as “simply being William Morris and having done the work of ten men.” In his obituaries, he was remembered primarily as a writer and was compared favorably with Tennyson and Browning. Morris was generally reticent on the question of his religious beliefs but there is abundant evidence that he thought of himself as an atheist and regarded Christianity as a beautiful mythology. He died of tuberculosis on 4 October 1896.

William Morris is buried in St George’s churchyard in Kelmscott, Oxfordshire, England. His gravestone was designed by his friend Philip Webb.